Wastewater testing for COVID-19 shows greater numbers than reported cases. That could affect decisions to reopen schools and businesses.

As authorities across the country struggle to provide enough COVID-19 tests, Chattanooga, TN, has turned to wastewater testing to detect the prevalence of the virus in the local population. Wastewater is used water that carries human waste from toilets, sinks, showers, washing machines, dishwashers, and other sources.

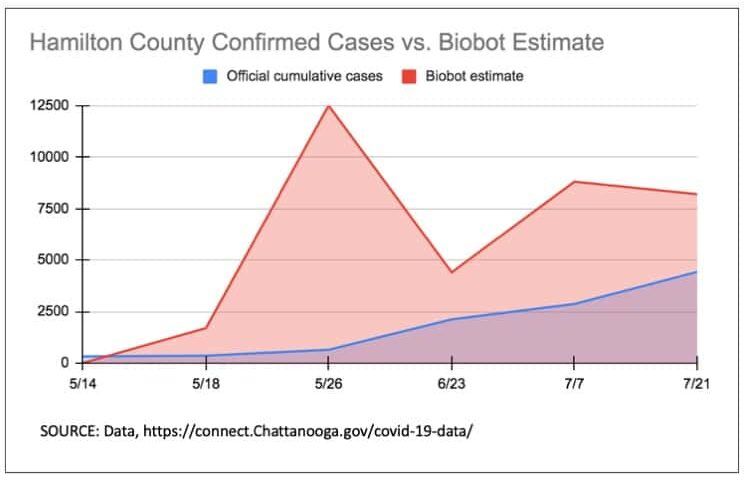

Initial results were alarming. On May 26th, the Hamilton County Health Department reported 642 cases of COVID-19 from positive individual tests. Biobot Analytics, the firm running the wastewater tests, estimated 12,500 cases on the same sampling date.

While wastewater testing is no replacement for individual COVID-19 tests, many scientists are calling for wider implementation of the method. “The U.S. needs to get started with wastewater surveillance now,” wrote Drs. Ashish K. Jha, David A. Larsen, and Anna Mehrotra in Stat News, citing the method’s success in monitoring polio levels and its potential as an early-warning system for future outbreaks

Local governments have taken notice. Without adequate individual testing, officials can’t accurately estimate the number of active cases in their communities – key information that informs decisions about opening schools and businesses. That’s a large part of why cities across the country, including Chattanooga, are using experimental wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) to complement data on active confirmed COVID-19 cases.

The state of individual testing for Covid-19

Rapid, efficient, accessible testing is critical to stopping the spread of COVID-19 — by quickly identifying people with the virus, authorities can trace their contacts and tell them to isolate.

In the spring, as the coronavirus spread throughout the United States, local authorities struggled to provide enough tests to their communities. For much of April, only about 150,000 tests were being done around the country each day. Epidemiologists were calling for many, many times that.

The reasons for the shortfall are complex. The healthcare supply chain struggled to provide enough swabs, reagent, and other necessary items. Labs lacked the personnel to run constant COVID-19 tests. The Trump administration resisted funding a nationwide testing program, and states have strict budgets that don’t allow room for unprecedented and unforeseen spending.

Testing capacity has since increased, with the US now performing over 725,000 tests per day. According to the CDC, as of this writing, 9% of tests are coming back positive. A high positivity rate can indicate that a significant proportion of cases in the community are going uncaptured. The WHO says that a daily positivity rate of 5% or less for 14 consecutive days is an indicator that most cases are being captured, meaning it might be safe for some level of reopening.

How do public health officials know if they are doing enough testing?

Better than simply counting total number of tests, the test positivity rate is a useful measure of whether enough tests are being done. The test positivity rate is simply the fraction of tests that come back positive.

According to the World Health Organization, before a region can relax restrictions or begin reopening, the test positivity rate from a comprehensive testing program should be at or below 5% for at least 14 days.

— Ronald D. Fricker, Jr., Professor of Statistics and Associate Dean for Faculty Affairs and Administration, Virginia Tech, excerpted from The Conversation

The potential of wastewater-based epidemiology

In the years since its original conception in 2001, governments have used WBE to detect population-level drug use, chemical exposure, and polio outbreaks. Now, cities across the country are using the method to estimate community cases of COVID-19. Biobot Analytics ran a national trial of coronavirus tests on about 350 municipal wastewater testing sites. The firm, along with several other analytics companies across the country, are providing wastewater testing for local governments.

A human infected with SARS-CoV2, the virus that leads to COVID-19, sheds viral material in their fecal matter at an average estimated rate. That fecal matter enters the municipal wastewater supply through the sewage system. Scientists can collect a sample of that water and test it for SARS-CoV2. By dividing the total amount of virus per day by the average virus shed per infected person per day, scientists can estimate how many active cases are present in the community.

According to Biobot Analytics, wastewater-based COVID-19 estimates can help “determine when to safely reopen”, “detect the re-emergence of COVID-19”, and “get an overview of the scope of the outbreak” for a fraction of the cost of individual tests.

These estimates are a work in progress, admit Biobot representatives. While WBE is an established epidemiological technique, its application to detect SARS-CoV2 is new. The interpretation notes on Biobot’s official data reports caution readers to “evaluate as beta results.”

Additionally, even with successful implementation of WBE, individual tests are still necessary to identify and isolate active cases of COVID-19.

Chattanooga signs wastewater testing contract

The City of Chattanooga was one of the municipalities that participated in Biobot’s May trial of COVID-19 wastewater testing. After the trial, Chattanooga opted to sign a contract for just under $24,000 with the firm to continue testing into 2021.

On May 14, Biobot’s testing did not detect any traces of the coronavirus in the water at Moccasin Bend, a treatment facility that processes water from Hamilton County and the surrounding area. The Hamilton County Health Department had reported 319 total cases and 33 new cases at the time. Later that month, on May 26, the Health Department reported 642 cases, compared to Biobot’s estimate of 12,500.

As noted in a pre-publication study co-authored by Biobot’s cofounders, “The reason for the discrepancy [between reported cases and WBE estimates] is not yet clear… and until further experiments are complete, these data do not necessarily indicate that clinical estimates are incorrect.” In other words, it could be the Biobot estimates, not the reported cases, that are wrong.

Nevertheless, the gap has narrowed in the weeks since. On July 21, the Health Department reported 4,424 cases compared to Biobot’s estimate of 8,200.

Chattanooga officials expressed cautious optimism in a June press conference. “It seems to be as accurate as we know of, right now,” said Jeff Rose, Director of Wastewater Systems at Moccasin Bend, the processing plant that serves the Chattanooga area.

One possible reason the initial Biobot testing did not capture confirmed cases in Hamilton County is that its estimates tend to be conservative. The company is “very particular on not detecting false positives,” explained Rose.

There are possible explanations for the spikes in estimated cases, as well. Some of the additional viral material could come from nearby areas outside of Hamilton County, and so would not be captured in the county’s official case count. Portions of Catoosa and Walker County’s wastewater are processed at Moccasin Bend and both have cases in the hundreds. Additionally, people who have had COVID-19 could shed the virus in their stool two weeks after they have recovered, further inflating estimates, explained Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University.

Not all cities that participated in the Biobot trial have opted to continue testing with the company. Cape Canaveral, FL, chose to sign a contract with a competing firm, Miami-based Source Molecular, due to pricing. After the trial period, Biobot would have charged $1,200 per sample while Source Molecular charges $350-$420 per sample. Source Molecular does not interpret test results, however.

Rose emphasized the importance of data interpretation in a statement to reporters. “What we see from other labs is they’d just give us a count of those genetic fragments, basically. So we would have to do some of our own interpretation as to what that means. And we don’t have a model [for doing that].”

For now, in place of more widespread individual testing, Chattanooga will rely on Biobot and its cutting edge science – despite its uncertainties – as the best available tool to help navigate the challenges of balancing public health with the reopening of schools and businesses.

To learn more about Chattanooga’s COVID-19 outbreak and read wastewater testing results, check out the city’s website.

Problem Addressed: Access to Healthcare

Written by Ciara McLaren

Published on Aug 10, 2020

Feature image: “Tenino WWTP Anoxic Basin” by XericX is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Sources

Wyatt Massey, “Chattanooga continues wastewater study after initial results showed thousands of unreported COVID-19 cases”, Chattanooga Times Free Press, Jul 9, 2020, https://www.timesfreepress.com/news/local/story/2020/jul/09/chattanoogcontinues-wastewater-study-covid-19/527179/#/questions/registration, accessed Aug 3

Sara Morrison, “Why America’s coronavirus testing problem is still so difficult to solve”, Vox, Apr 24, 2020, https://www.vox.com/recode/2020/4/24/21229774/coronavirus-covid-19-testing-social-distancing, accessed Aug 3

Maria Lorenzo and Yolanda Picó, “Wastewater-based epidemiology: current status and future prospects”, Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health, Jun 2019, pgs 77-84, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2468584418300965, accessed Aug 3

Fuqing Wu, Amy Xiao, Jianbo Zhang, Xiaoqiong Gu, Wei Lin Lee, Kathryn Kauffman, William Hanage, Mariana Matus, Newsha Ghaeli, Noriko Endo, Claire Duvallet, Katya Moniz, Timothy Erickson, Peter Chai, Janelle Thompson, Eric Alm, “SARS-CoV-2 titers in wastewater are higher than expected from clinically confirmed cases”, medRxiv, Apr 7, 2020, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.05.20051540v1, accessed Aug 3, 2020

The COVID Tracking Project, “US Historical Data”, Aug 3, 2020, https://covidtracking.com/data/us-daily, accessed Aug 3, 2020

John Hopkins, “WHICH U.S. STATES MEET WHO RECOMMENDED TESTING CRITERIA?”, Aug 3, 2020, https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/testing/testing-positivity, accessed Aug 3, 2020

Sharon Begley, “Wastewater testing gains traction as a Covid-19 early warning system”, Stat News, May 28, 2020, https://www.statnews.com/2020/05/28/wastewater-testing-gains-support-as-covid19-early-warning/, accessed Aug 3

Walker County, GA, “COVID-19 Updates from Walker County”, https://walkercountyga.gov/covid19/, accessed Aug 3

Jim Waymer, “Cape Canaveral finds more coronavirus in city sewage”, Florida Today, Jul 17, 2020, https://www.floridatoday.com/story/news/2020/07/17/cape-canaveral-finds-more-coronavirus-genes-city-sewage/5460328002/, accessed Aug 3

Ronald D. Fricker, “Test positivity rate: How this one figure explains that the US isn’t doing enough testing yet”, The Conversation, Jul 30, 2020, https://theconversation.com/test-positivity-rate-how-this-one-figure-explains-that-the-us-isnt-doing-enough-testing-yet-143340, accessed Aug 6

City of Chattanooga Zoom press conference, Jun 2020, accessed Aug 6

Have a Suggestion?

Know a leader? Progress story? Cool tool? Want us to cover a new problem?