Introduction

Immigration is a fact of American life deeply embedded in the nation’s history, politics, economics, and culture. In some respect, immigration policy has paralleled the difficult task of addressing the legacy of slavery in modern American life and the challenges of creating space for Indigenous people whose traditional lands were taken during a period of often-violent expansion. However, whereas the law has moved steadily toward greater respect for the rights of Black and Indigenous people, it remains more indifferent to the place of immigrants in our society, subject as it is to a fungible set of goals based on economic need, political objectives, humanitarian impulses, and strategic opportunity.

The United States has long been considered a nation of immigrants, with a larger foreign-born population than any other country in the world. Immigration policies determine which people and how many can legally immigrate to the US, and by what processes they are able to enter the country. They also determine the rights and restrictions immigrants face as they integrate into American society.

Closely related to immigration issues are naturalization policies which dictate how immigrants can claim the full rights of US citizenship. Laws regarding immigration and citizenship affect many areas of national importance, including voter eligibility, labor competition, national security, international relations, economic development, availability of resources, and the character of U.S. society. At the same time, these areas influence the making of our laws and policies.

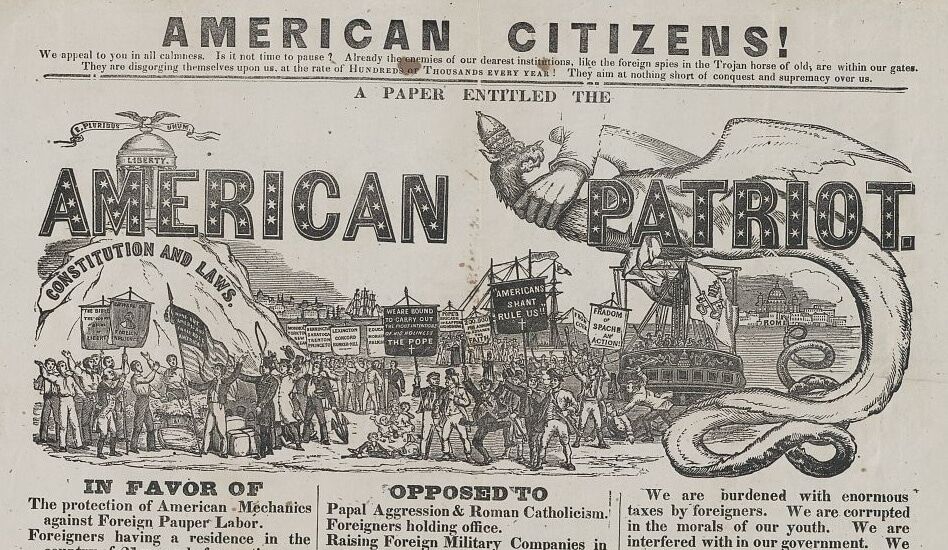

As a nation, we have struggled to balance these competing priorities in the making of immigration policy. Immigrants and their inclusion in American life have been vital to the nation’s economic growth, yet the question of who we let in has at times served as a politically divisive issue used in policy negotiations and election campaigns. Unlike both Black and Indigenous groups, who were long a part of the fabric of the nation, the introduction of new immigrant populations has consistently met with resistance from more established immigrant groups who feared competition for jobs and political power, and who sometimes assumed a nativist view of their US identity. This has been true since passage of the first naturalization act in 1790, and it has never been more so than in recent years, as the immigrant population is on track to turn the country’s White majority into a minority.

“A nation founded on the idea that all men are created equal and endowed with inalienable rights and offering asylum to anyone suffering from persecution is a beacon to the world. This is America at its best ….”

–– Jill Lepore, This America: The Case for the Nation

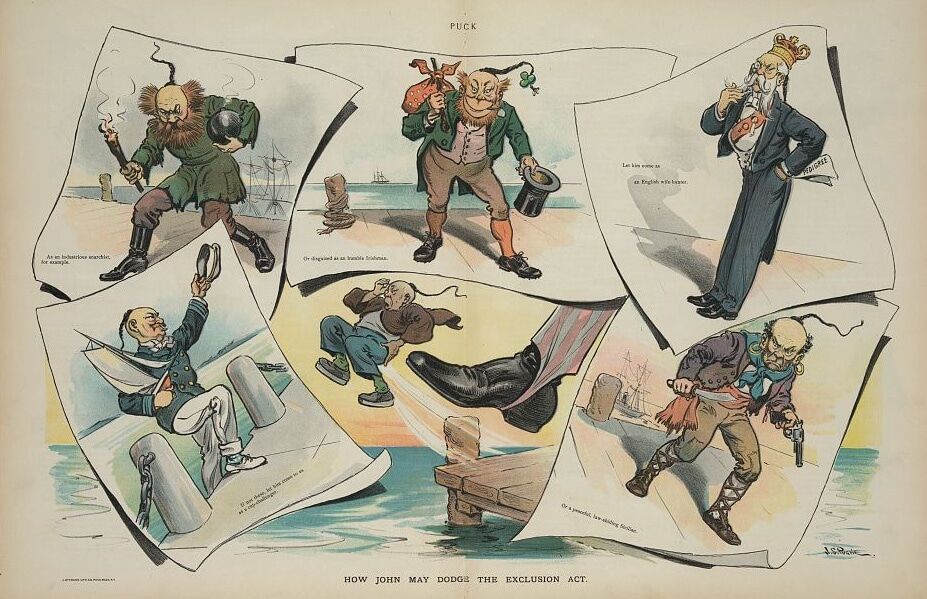

The arrival of new immigrants is often accompanied by the fear that they will take jobs and resources away from those already living and working here while also driving down wages. Fear of labor competition, though generally but not always unfounded, is typically followed by backlash against immigrants which fuels more restrictive policy. This was the case for laws such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, and the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) of 1996. While these laws were promoted as addressing economic concerns, their design was motivated by racist and xenophobic sentiment.

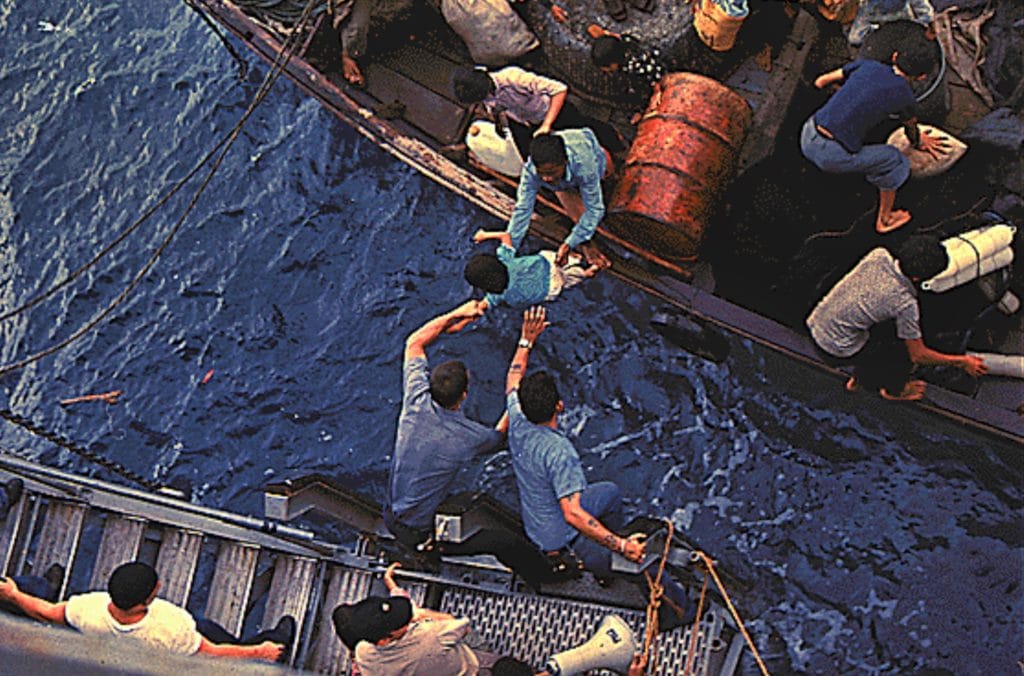

On the other hand, labor shortages usually lead to a more welcoming immigration policy. The Bracero Program of 1942, the Immigration Act of 1990, and the exemption of foreign-born agricultural workers from COVID-related immigration restrictions illustrate the malleability of immigration policy in support of the country’s economic growth. Likewise, the nation’s leadership in advocating for human rights around the world during the second half of the 20th century put pressure on lawmakers to enact more humanitarian immigration policies at home, as reflected in the Displaced Persons Act of 1948, the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, and the Refugee Act of 1980.

Even before the country emerged as a global leader after World War II, the US presence on the world stage meant that entanglements with other nations would complicate immigration policy. The Gentleman’s Agreement of 1907 limited Japanese immigration so as to maintain good relations with Japan as a counter to Russian expansion. The Magnuson Act of 1943 reopened the door for Chinese immigration after China became an official ally of the US during World War II. And the 1966 Cuban Adjustment Act created a pathway to permanent residency status for Cubans who fled communist Cuba. Passage of these and other laws reflect the influence of international relations and global scrutiny on American immigration policy.

Today, US immigration policy reflects a mix of all these influences: humanitarianism, economic need, real and imagined national security and employment concerns, racism, nationalism, and political opportunism. The timeline that follows is broken into five distinct turning points that illustrate how the ebb and flow of immigration and shifting priorities have influenced the evolution of US immigration policy.

Hypocrisy and the Nazis

It is worth noting that historian Jill Lepore, after writing the statement quoted above, immediately clarified that “a nation founded on ideals, [and] universal truths, also opens itself to charges of hypocrisy at every turn.” Lepore’s clarification aptly describes circumstances in the United States. Historian James Q. Whitman made that quite clear in his examination of Nazi records, where he found references by Hitler and others to American race and immigration law as a model for Nazi Germany. While the aspirations expressed in the Emma Lazarus poem, “The New Colossus”, and our concept of the melting pot may have contributed to a more humanitarian perspective on immigration, real and imagined fears have kept the nation from establishing a constant set of immigration policies designed to foster the integration and acceptance of immigrants into our communities.

Immigration Law Timeline

Sources

The URLs included with the sources below were good links when we published. However, as third party websites are updated over time, some links may be broken. We do not update these broken links. If you are interested in the source, it may be possible to find it by copying and pasting the URL into a search on the Internet Archive Wayback Machine. From the search results, be sure to choose a date from around the time our article was published.

National Archives, “Major United States Laws Relating to Immigration and Naturalization: 1790–2005”, November 2014, https://www.archives.gov/files/research/naturalization/420-major-immigration-laws.pdf, accessed Jul 3, 2020.

Introduction

Jill Lepore, “This America: The Case for the Nation”, p. 46, Liveright, 2019, Kindle Edition

James Q. Whitman, “Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law”, Princeton UP, 2017, Kindle Edition

Push for National Identity, Votes, Westward Expansion

Philip Martin, “Trends in Migration to the U.S.”, Population Reference Bureau, May 19, 2014, https://www.prb.org/us-migration-trends/#:~:text=The%20third%20wave%2C%20between%201880,States%20had%2075%20million%20residents.&text=Immigration%20rose%20after%20World%20War,European%20spouses%20and%20Europeans%20migrated, accessed Sep 22, 2020

History.com, “US Immigration Before 1965”, History.com, Oct 29, 2009, https://www.history.com/topics/immigration/u-s-immigration-before-1965, accessed Jul 3 2020

Shiho Imai, “Naturalization Act of 1790”, Densho Encyclopedia https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Naturalization%20Act%20of%201790/, accessed Jan 16 2020

Rudolph J. Vecoli, “The Significance of Immigration in the Formation of an American Identity”, The History Teacher, vol. 30, no. 1, 1996, pp. 9–27, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/494217, accessed Jul 3, 2020

History.com, “Alien and Sedition Acts”, Nov 9, 2009, https://www.history.com/topics/early-us/alien-and-sedition-acts, accessed Jul 3, 2020

William J. Watkins, “Reclaiming the American Revolution: the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions and Their Legacy”, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008

Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Know-Nothing Party”, May 2020, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Know-Nothing-party, accessed Jul 3, 2020

Lorraine Boissoneault, “How the 19th-Century Know Nothing Party Reshaped American Politics”, Smithsonian Magazine, Jan 26, 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/immigrants-conspiracies-and-secret-society-launched-american-nativism-180961915/, accessed Jul 3, 2020

Immigration History, “Immigration Act of 1864”, Immigration and Ethnic History Society, https://immigrationhistory.org/item/immigration-act-of-1864/, accessed Jan 17, 2020

American Emigrant Company, “Considerations in favor of the accompanying proposed amendments to the Act entitled an Act to encourage Immigration”, Widener Library, Open Collections Program at Harvard University, https://id.lib.harvard.edu/curiosity/immigration-to-the-united-states-1789-1930/39-990105837210203941, accessed Sep 29, 2020

“Act to Encourage Immigration”, St. James Encyclopedia of Labor History Worldwide: Major Events in Labor History and Their Impact, Encyclopedia.com, Jan 16, 2020, https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/act-encourage-immigration, accessed Jul 3 2020

“Naturalization Act of 1870”, Immigration and Multiculturalism: Essential Primary Sources, Encyclopedia.com, updated Jun 29, 2020, https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/applied-and-social-sciences-magazines/naturalization-act-1870, accessed Jul 3 2020

Hostility and Myth Building

Wikipedia, “Chy Lung v. Freeman”, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chy_Lung_v._Freeman, accessed Sep 22, 2020

USCIS, “Early American Immigration Policies”, Dec 4, 2019, https://www.uscis.gov/history-and-genealogy/our-history/overview-ins-history/early-american-immigration-policies#:~:text=After%20certain%20states%20passed%20immigration,began%20to%20pass%20immigration%20legislation., accessed Jul 3 2020

Philip Martin, “Trends in Migration to the US”, Population Reference Bureau, May 19, 2014, https://www.prb.org/us-migration-trends/#:~:text=The%20third%20wave%2C%20between%201880,States%20had%2075%20million%20residents.&text=Immigration%20rose%20after%20World%20War,European%20spouses%20and%20Europeans%20migrated., accessed Jul 3 2020

Library of Congress, “Immigration to the United States, 1851 -1900”, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/rise-of-industrial-america-1876-1900/immigration-to-united-states-1851-1900/, accessed Sep 30, 2020

Global Boston, “Second Wave Immigration, 1880 – 1921”, Boston College, https://globalboston.bc.edu/index.php/home/eras-of-migration/test-page-2/, accessed Sep 30, 2020

Library of Congress, “Immigrants in the Progressive Era”, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/progressive-era-to-new-era-1900-1929/immigrants-in-progressive-era/, accessed Sep 25, 2020

Marian L. Smith, “INS Administration of Racial Provisions in U.S. Immigration and Nationality Law Since 1898”, Prologue Magazine/National Archives, Summer 2002, Vol. 34, No. 2, https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2002/summer/immigration-law-1.html, accessed Dec 17, 2020

Immigration History, “Chinese Exclusion Act Aka ‘An Act to Execute Certain Treaty Stipulations Relating to Chinese’”, Immigration and Ethnic History Society, https://immigrationhistory.org/item/an-act-to-execute-certain-treaty-stipulations-relating-to-chinese-aka-the-chinese-exclusion-law/, accessed Jan 17, 2020

Library of Congress, “Searching for the Gold Mountain”, https://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/presentationsandactivities/presentations/immigration/chinese2.html#:~:text=Word%20of%20a%20mountain%20of,%2C%20or%20%22gold%20mountain%22., accessed Jul 3 2020

Office of the Historian, “Chinese Immigration and the Chinese Exclusion Acts”, US Department of State, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1866-1898/chinese-immigration, accessed Jul 3 2020

USCIS, “Origins of the Federal Immigration Service”, https://www.uscis.gov/history-and-genealogy/our-history/overview-ins-history/origins-federal-immigration-service, accessed Jul 3, 2020

History.com, “Ellis Island”, Oct 27, 2009, https://www.history.com/topics/immigration/ellis-island, accessed Jul 3, 2020

Wikipedia, “Geary Act”, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geary_Act, accessed Sep 25, 2020

Immigration History, “Geary Act (1892)”, Immigration and Ethnic History Society, https://immigrationhistory.org/item/geary-act/, accessed Jul 3, 2020

OurDocuments.gov, “Chinese Exclusion Act (1882)”, https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=47, accessed Dec 18, 2020

Kerry Abrams, “Polygamy, Prostitution, and the Federalization of Immigration Law”, Columbia Law Review 105, no. 3 (April 2005): 641–716

James S. Pula, “American Immigration Policy and the Dillingham Commission”, Polish American Studies, vol. 37, no. 1, 1980, pp. 5–31, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20148034, accessed Jul 4, 2020

History.com, “Gentlemen’s Agreement”, Oct 29, 2009, https://www.history.com/topics/immigration/gentlemens-agreement, accessed Jul 4, 2020

Cherstin Lyon, “Immigration Act of 1917”, Densho Encyclopedia, Jul 17, 2015, https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Immigration%20Act%20of%201917, accessed Jul 4, 2020

Immigration History, “Immigration Act of 1917 (Barred Zone Act)”, Immigration and Ethnic History Society, Jan 1, 1970, https://immigrationhistory.org/item/1917-barred-zone-act/, accessed Jul 4, 2020

Brenda Barrientes, “1921 Emergency Quota Law (An Act to Limit the Immigration of Aliens into the United States)”, US Immigration Legislation: 1921 Emergency Quota Law, http://library.uwb.edu/Static/USimmigration/1921_emergency_quota_law.html, accessed Jul 4, 2020

Claudia Goldin, “The Political Economy of Immigration Restriction in the United States, 1890-1921”, National Bureau of Economic Research, April 1993, http://www.nber.org/chapters/c6577, accessed Jul 4, 2020

Immigration History, “Emergency Quota Law (1921)”, Immigration and Ethnic History Society, Jan 1, 1970. https://immigrationhistory.org/item/

Immigration History, “Immigration Act of 1924 (Johnson-Reed Act)”, Immigration and Ethnic History Society, Jan 1, 1970, https://immigrationhistory.org/item/1924-immigration-act-johnson-reed-act/, accessed Jul 4, 2020

U.S. Customs and Border Protection, “Border Patrol History”, Oct 5, 2018, https://www.cbp.gov/border-security/along-us-borders/history, accessed Jul 4, 2020

Mae M. Ngai, “The Architecture of Race in American Immigration Law: A Reexamination of the Immigration Act of 1924”, The Journal of American History, vol. 86, no. 1, 1999, pp. 67-92, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2567407, accessed Jul 4, 2020

Library of Congress, “United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind”, https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/usrep/usrep261/usrep261204/usrep261204.pdf, accessed Nov 8, 2020

Shiho Imai, “Ozawa v. United States”, Densho Encyclopedia, April 16, 2014, http://encyclopedia.densho.org/Ozawa_v._United_States/, accessed Nov 4, 2020

Immigration History, “Ozawa v. United States (1922)”, https://immigrationhistory.org/item/takao-ozawa-v-united-states-1922/, accessed Nov 4, 2020

Immigration History, “Thind v. United States (1923)”, https://immigrationhistory.org/item/thind-v-united-states%E2%80%8B/, accessed Nov 8, 2020

U.S. Customs and Border Protection, “1891: Immigration Inspection Expands”, Mar 21, 2014, https://www.cbp.gov/about/history/1891-imigration-inspection-expands, accessed Nov 12, 2020

National Park Service, “Closing the Door on Immigration”, https://www.nps.gov/articles/closing-the-door-on-immigration.htm, accessed Nov 12, 2020

Kelly Lytle Hernandez, “How crossing the US-Mexico border became a crime”, The Conversation, Apr 30, 2017, https://theconversation.com/how-crossing-the-us-mexico-border-became-a-crime-74604, accessed Nov 12, 2020

Depression, War Ease Restrictions

Migration Policy Institute, “US Immigrant Population and Share over Time, 1850-Present”, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/immigrant-population-over-time, accessed Jul 4, 2020

US Citizenship and Immigration Services, “Post-War Years”, History Office and Library, https://www.uscis.gov/history-and-genealogy/our-history/overview-ins-history/post-war-years, accessed Jul 4, 2020

Barbara A. Driscoll, The Tracks North: The Railroad Bracero Program of World War II, CMAS Books/Center for Mexican American Studies, the University of Texas at Austin, 1999, https://search.library.dartmouth.edu/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=alma991019860609705706&context=L&vid=01DCL_INST:01DCL&lang=en&search_scope=MyInst_and_CI&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine&tab=All&query=any,contains,bracero%20program, accessed Jul 4, 2020

Natalia Molina, “Borders, Laborers, and Racialized Medicalization Mexican Immigration and US Public Health Practices in the 20th Century”, Am J Public Health, 2011 June; 101(6): 1024–1031, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3093266/, accessed Dec 18, 2020

Bracero History Archive, http://braceroarchive.org/about, accessed Dec 18, 2020

History.com, “US and Mexico sign the Mexican Farm Labor Agreement”, Oct 7, 2019, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/us-mexico-sign-mexican-farm-labor-agreement-bracero-program, accessed Jul 4, 2020

Office of the Historian, “Repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act, 1943”, US Department of State, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1937-1945/chinese-exclusion-act-repeal, accessed Jul 4, 2020

Immigration History, “Real of Chinese Exclusion (1943)”, Immigration and Ethnic History Society, https://immigrationhistory.org/item/1943-repeal-of-chinese-exclusion/, accessed Jul 4, 2020

US Citizenship and Immigration Services, “Refugee Timeline”, https://www.uscis.gov/history-and-genealogy/featured-stories-uscis-history-office-and-library/refugee-timeline, accessed Jul 4, 2020

John Boyd, “Displaced Persons Act of 1948”, Immigration to the United States, https://immigrationtounitedstates.org/464-displaced-persons-act-of-1948.html, accessed Jul 4, 2020

Deborah Ankar, “US Immigration and Asylum Policy: A Brief Historical Perspective.” In Defense of the Alien, vol. 13, 1990, pp. 74–85. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23143024, accessed Jul 4, 2020

Office of the Historian, “The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (The McCarran-Walter Act)”, US Department of State, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1945-1952/immigration-act, accessed Jul 4, 2020

Anna O’Leary, Undocumented Immigrants in the United States: An Encyclopedia of Their Experience , Greenwood, 2014, pp. 372-374, accessed Jul 4, 2020

Brent Funderburk, “Operation Wetback”, Encyclopædia Britannica, Sep 4, 2017, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Operation-Wetback, accessed Jul 4, 2020

Erin Blakemore, “The Largest Mass Deportation in American History”, History.com, Jun 18, 2019, https://www.history.com/news/operation-wetback-eisenhower-1954-deportation, accessed Jul 4, 2020

History, Art & Archives, US House of Representatives, “Depression, War, and Civil Rights”, https://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/HAIC/Historical-Essays/Separate-Interests/Depression-War-Civil-Rights/, accessed Jul 4, 2020

History.com, “Japanese Internment Camps”, Oct 29, 2009, https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/japanese-american-relocation, accessed Nov 4, 2020

History.com, “FDR orders Japanese Americans into internment camps”, Nov 16, 2009, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/fdr-signs-executive-order-9066, accessed Nov 4, 2020

Encyclopædia Britannica, “Japanese American Internment”, Apr 14, 2020, www.britannica.com/event/Japanese-American-internment, accessed Nov 7, 2020

Kevin P. Duffus, “U-Boats off the Outer Banks”, NCpedia, 2008, https://www.ncpedia.org/history/20th-Century/wwii-uboats, accessed Nov 8, 2020

Jonathan Yardley, “When Nazis prowled the U.S. coast”, Washington Post, Apr 25, 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/head-here/2014/04/25/aa5c8202-c3d5-11e3-b195-dd0c1174052c_story.html, accessed Nov 8, 2020

“Facts and Case Summary – Korematsu v. U.S.”, United States Courts, https://www.uscourts.gov/educational-resources/educational-activities/facts-and-case-summary-korematsu-v-us, accessed Nov 7, 2020

OurDocuments.gov, “Executive Order 9066: Resulting in the Relocation of Japanese (1942)”, https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=74#, accessed Nov 8, 2020

Natalie Walker, “The Displaced Persons Act of 1948”, Truman Library Institute, Apr 29, 2019, https://www.trumanlibraryinstitute.org/the-displaced-persons-act-of-1948/, accessed Nov 12, 2020

Global Responsibilities Expand Entry

James Q. Whitman, Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law, p. 12, Princeton UP, 2017, Kindle Edition

History.com, “U.S. Immigraton Since 1965”, Jun 7, 2019, https://www.history.com/topics/immigration/us-immigration-since-1965, accessed Sep 26, 2020

Pew Research Center, “Chapter 5: US Foreign Born Population Trends”, Sep 28, 2015, https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2015/09/28/chapter-5-u-s-foreign-born-population-trends/, accessed Jul 7, 2020

Pew Research Center, “Modern Immigration Wave Brings 59 Million to US, Driving Population Growth and Change through 2065”, Sep 28, 2015, https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2015/09/28/modern-immigration-wave-brings-59-million-to-u-s-driving-population-growth-and-change-through-2065/#:~:text=As%20a%20result%20of%20its,1965%20to%2018%25%20in%202015, accessed Jul 7, 2020

Abby Budiman, “Key findings about U.S. immigrants”, Pew Research Center, Aug 20, 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/20/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/, accessed Sep 27, 2020

Lori Robertson, “Illegal Immigration Statistics”, FactCheck.org, Jun 7, 2019, https://www.factcheck.org/2018/06/illegal-immigration-statistics/, accessed Sep 27, 2020

Congressional Research Service, “Central American Migration: Root Causes and US Policy”, Jun 13, 2019, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/IF11151.pdf, accessed Jul 7, 2020

Emma Newburger, Tucker Higgins, “Secretive cabals, fear of immigrants and the tea party: How the financial crisis led to the rise of Donald Trump”, CNBC, September 11, 2018, https://www.cnbc.com/2018/09/10/how-the-financial-crisis-led-to-the-rise-of-donald-trump.html, accessed Jul 7, 2020

Daniel Cox, Rachel Lienesch, Robert P. Jones, “Beyond Economics: Fears of Cultural Displacement Pushed the White Working Class to Trump”, PRRI / The Atlantic, May 9, 2017, https://www.prri.org/research/white-working-class-attitudes-economy-trade-immigration-election-donald-trump/, accessed Jul 7, 2020

Sarah Pierce, Andrew Selee, “Immigration under Trump: A Review of Policy Shifts in the Year since the Election”, Migration Policy Institute, Dec 2017, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/TrumpatOne-final.pdf, downloaded Jul 7, 2020

Alex Nowrasteh, “President Trump’s Lasting Immigration Legacy”, Cato Institute, Nov 9, 2020, https://www.cato.org/blog/president-trumps-lasting-immigration-legacy, accessed Dec 29, 2020

T.J. Hatton, “United States Immigration Policy: The 1965 Act and its Consequences”, Scand. J. of Economics, 2015, 117: 347-368. doi:10.1111/sjoe.12094, accessed Jul 4, 2020

Jeanne Batalova, Brittany Blizzard, Jessica Bolter, “Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States”, Migration Policy Institute, Feb 14, 2020, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/frequently-requested-statistics-immigrants-and-immigration-united-states, accessed Jul 7, 2020

Muzaffar Chishti, Faye Hipsman, Isabel Ball, “Fifty Years On, the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act Continues to Reshape the United States”, Migration Policy Institute, Oct 15, 2015,

https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/fifty-years-1965-immigration-and-nationality-act-continues-reshape-united-states, accessed Jul 4, 2020

Transcript, “January 8, 1964: State of the Union”, UVA Miller Center, https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/january-8-1964-state-union, accessed Oct 1, 2020

Jerry Kammer, “The Hart-Celler Immigration Act of 1965”, Center for Immigration Studies, Sep 30, 2015, https://cis.org/Report/HartCeller-Immigration-Act-1965, accessed Sep 28, 2020

Deborah E. Anker & Michael H. Posner, “The Forty Year Crisis: A Legislative History of the Refugee Act of 1980”, San Diego Law Review vol. 19 (1981), https://digital.sandiego.edu/sdlr/vol19/iss1/3, downloaded Jul 7, 2020

National Archives Foundation, “Refugee Act of 1980”, https://www.archivesfoundation.org/documents/refugee-act-1980/, accessed Jul, 7 2020

Doris Meissner et al, “Immigration Enforcement in the United States: The Rise of a Formidable Machinery”, Migration Policy Institute, Jan 2013, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/pubs/enforcementpillars.pdf, downloaded Jul 7, 2020

Muzaffar Chishti, Doris Meissner, Claire Bergeron, “At Its 25th Anniversary, IRCA’s Legacy Lives On”, Migration Policy Institute, Nov 16, 2011, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/its-25th-anniversary-ircas-legacy-lives, accessed Jul 7, 2020

Muzaffar Chishti, Charles Kamasaki, “IRCA in Retrospect: Guide Posts for Today’s Immigration Reform”, Migration Policy Institute, Jan 2014, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/irca-retrospect-immigration-reform, downloaded Jul 7, 2020

Immigration History, “Immigration Act of 1990”, Immigration and Ethnic History Society. https://immigrationhistory.org/item/immigration-act-of-1990/, accessed Jul 7, 2020

Muzaffar Chishti, Stephen Yale-Loehr, “The Immigration Act of 1990: Unfinished Business a Quarter-Century Later”, Migration Policy Institute, Jul 2016, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/immigration-act-1990-still-unfinished-business-quarter-century-late, downloaded Jul 7, 2020

Audrey Singer, “Welfare Reforms and Immigrants”, Brookings Institute, Feb 2, 2004, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/200405_singer.pdf, downloaded Jul 7, 2020

Ballotpedia, “Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996”, https://ballotpedia.org/Illegal_Immigration_Reform_and_Immigrant_Responsibility_Act_of_1996, accessed Sep 28, 2020

Kate M. Manuel, “Unauthorized Aliens, Higher Education, InState Tuition, and Financial Aid: Legal Analysis”, Congressional Research Service, Jan 11, 2016, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43447.pdf, downloaded Jul 7, 2020

Ballotpedia, “Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act”, https://ballotpedia.org/Personal_Responsibility_and_Work_Opportunity_Reconciliation_Act_of_1996, accessed Sep 28, 2020

Ballotpedia, “Enhanced Border Security and Visa Entry Reform Act”, https://ballotpedia.org/Enhanced_Border_Security_and_Visa_Entry_Reform_Act_of_2002, accessed Sep 28, 2020

Immigration History, “Homeland Security Act (2002)”, Immigration and Ethnic History Society. https://immigrationhistory.org/item/homeland-security-act/, accessed Jul 7, 2020

Tom Murse, “Department of Homeland Security History”, ThoughtCo., Oct 23, 2019, https://www.thoughtco.com/department-of-homeland-security-4156795, accessed Sep 28, 2020

US Citizenship and Immigration Services, “Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA)”, https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/Humanitarian/Deferred%20Action%20for%20Childhood%20Arrivals/DACA-toolkit.pdf, downloaded Jul 7, 2020

American Immigration Council, “The Dream Act, DACA, and Other Policies Designed to Protect Dreamers”, Aug, 2019, https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/dream-act-daca-and-other-policies-designed-protect-dreamers, downloaded Jul 7, 2020

Muzaffar Chishti, Sarah Pierce, Jessica Bolter, “The Obama Record on Deportations: Deporter in Chief or Not?”, Migration Policy Institute, Jan 26, 2017, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/obama-record-deportations-deporter-chief-or-not, downloaded Jul 7, 2020

Alicia A. Caldwell, Louise Radnofsky, “Why Trump Has Deported Fewer Immigrants than Obama”, Wall Street Journal, Aug 3, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/why-trump-has-deported-fewer-immigrants-than-obama-11564824601, accessed Jul 7 2020

Sara Rimer, “Has Door From Cuba Been Held Open?”, The Brink/Boston University, Aug 26, 2015, http://www.bu.edu/articles/2015/cuban-immigration/, accessed Nov 7, 2020

US Citizenship and Immigration Services, “Green Card for a Cuban Native or Citizen”, https://www.uscis.gov/green-card/green-card-eligibility/green-card-for-a-cuban-native-or-citizen, accessed Nov 7, 2020

Immigration History, “Cuban Adjustment Act of 1966”, https://immigrationhistory.org/item/cuban-adjustment-act-of-1966/, accessed Nov 7, 2020

Ilisa Mira, “Seven Things You Should Know About Cuban Adjustment”, CLINIC, Sep 27, 2016, https://cliniclegal.org/resources/humanitarian-relief/seven-things-you-should-know-about-cuban-adjustment, accessed Nov 7, 2020

Brittany Blizzard and Jeanne Batalova, “Cuban Immigrants in the United States”, Migration Policy Institute, Jun 11, 2020, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/cuban-immigrants-united-states-2018, accessed Nov 7, 2020

Jorge Duany, “Cuban Migration: A Postrevolution Exodus Ebbs and Flows”, Migration Policy Institute, Jul 6, 2017, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/cuban-migration-postrevolution-exodus-ebbs-and-flows, accessed Nov 7, 2020

Immigration History, “Deferred Action for Parents of U.S. Citizens and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA) and DACA Program Expanded”, https://immigrationhistory.org/item/deferred%E2%80%8B-action-for-parents-of-americans-and-lawful-permanent-residents-dapa-and-daca-program-expanded/, accessed Nov 11, 2020

American Immigration Council, “Temporary Protected Status: An Overview”, Feb 2, 2020, https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/temporary-protected-status-overview, accessed Dec 8, 2020

UN High Commissioner for Refugees, “The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol”, Sep 2011, https://www.refworld.org/docid/4ec4a7f02.html, accessed Dec 8, 2020

White Identity, Nativism Color Immigration Actions

Daniel Cox, Rachel Lienesch, Robert P. Jones, “Beyond Economics: Fears of Cultural Displacement Pushed the White Working Class to Trump”, PRRI / The Atlantic, May 9, 2017, https://www.prri.org/research/white-working-class-attitudes-economy-trade-immigration-election-donald-trump/, accessed Jul 7, 2020

Sarah Pierce, Andrew Selee, “Immigration under Trump: A Review of Policy Shifts in the Year since the Election”, Migration Policy Institute, December 2017, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/TrumpatOne-final.pdf, downloaded Jul 7, 2020

Pew Research Center, “Modern Immigration Wave Brings 59 Million to US, Driving Population Growth and Change through 2065”, Sep 28, 2015, https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2015/09/28/modern-immigration-wave-brings-59-million-to-u-s-driving-population-growth-and-change-through-2065/#:~:text=As%20a%20result%20of%20its,1965%20to%2018%25%20in%202015, accessed Jul 7, 2020

Sarah Sidner, Rachel Clarke, “Former Breitbart Editor: Stephen Miller is a white supremacist. I know, I was one too.”, CNN, Dec 16, 2019, https://www.cnn.com/2019/12/13/politics/katie-mchugh-stephen-miller/index.html, accessed Sep 28, 2020

Perry Bacon Jr., “What is Really Behind Trump’s Controversial Immigration Policies?”, FiveThirtyEight, Jun 19, 2018, https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/what-is-really-behind-trumps-controversial-immigration-policies/, accessed Sep 28, 2020

Peniel Ibe, “Trump’s attacks on the legal immigration system explained”, American Friends Service Committee, Apr 23, 2020, https://www.afsc.org/blogs/news-and-commentary/trumps-attacks-legal-immigration-system-explained, accessed Sep 28, 2020

Emma Newburger, Tucker Higgins, “Secretive cabals, fear of immigrants and the tea party: How the financial crisis led to the rise of Donald Trump”, CNBC, Sep 11, 2018, https://www.cnbc.com/2018/09/10/how-the-financial-crisis-led-to-the-rise-of-donald-trump.html, accessed Jul 7, 2020

Sarah Pierce, Jessica Bolter, “Dismantling and Reconstructing the U.S. Immigration System: A Catalog of Changes under the Trump Presidency”, Migration Policy Institute, Jul 2020, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/news/mpi-report-catalogs-immigration-executive-actions-trump-presidency, accessed Dec 8, 2020

Anthony L. Fisher, “’Hatemonger’ author Jean Guerrero on Stephen Miller, white nationalism, and performative cruelty”, Business Insider, Apr 10, 2020, https://www.businessinsider.com/hatemonger-jean-guerrero-interview-stephen-miller-white-nationalism-and-2020-8, accessed Sep 28, 2020

Andrea González-Ramírez, “The White Nationalist Education of Stephen Miller”, GEN, Aug 7, 2020, https://gen.medium.com/the-white-nationalist-education-of-stephen-miller-3d69f5f19964, accessed Sep 28, 2020

American Immigration Council, “A Primer on Expedited Removal”, Jul 22, 2019, https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/primer-expedited-removal, accessed Sep 28, 2020

Center for Migration Studies, “President Trump’s Executive Orders on Immigration and Refugees”, https://cmsny.org/trumps-executive-orders-immigration-refugees/, accessed Sep 28, 2020

Muzaffar Chishti, Sarah Pierce, and Laura Plata, “In Upholding Travel Ban, Supreme Court Endorses Presidential Authority While Leaving Door Open for Future Challenges”, Migration Policy Institute, Jun 29, 2018, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/upholding-travel-ban-supreme-court-endorses-presidential-authority-while-leaving-door-open, accessed Jul 4, 2020

Andrew S. Pyle, Darren L. Linvill, S. Paul Gennett, “From silence to condemnation: Institutional responses to “travel ban” Executive Order 13769”, Public Relations Review, vol 44, no. 2, 2018, pp. 214-223, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2017.11.002, accessed Jul 4, 2020

Angelo Paparello, “Revanchist Immigration: The Aftermath of “Buy American, Hire American”, Seyfarth | BIG Immigration Blog, Jan 4, 2018, https://www.bigimmigrationlawblog.com/2018/01/home-uscis-revanchist-immigration-the-aftermath-of-buy-american-hire-american-revanchist-immigration-the-aftermath-of-buy-american-hire-american/, accessed Sep 28, 2020

Sarah Pierce, Jessica Bolter, Andrew Selee, “US Immigration Policy Under Trump: Deep Changes and Lasting Impacts”, Transatlantic Council on Migration, 2018, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/us-immigration-policy-trump-deep-changes-impacts, downloaded Jul 6, 2020

Elijah E. Cummings, “Child Separations by the Trump Administration”, Committee on Oversight and Reform, Jul 2019, https://oversight.house.gov/sites/democrats.oversight.house.gov/files/2019-07-2019.%20Immigrant%20Child%20Separations-%20Staff%20Report.pdf, downloaded Jul 6, 2020

Liz Vinson, “Family separation policy continues two years after Trump administration claims it ended”, Southern Poverty Law Center, Jun 18, 2020, https://www.splcenter.org/news/2020/06/18/family-separation-policy-continues-two-years-after-trump-administration-claims-it-ended, accessed Sep 28, 2020

NAFSA, “Immigration Executive Actions Under the Trump Administration”, https://www.nafsa.org/professional-resources/browse-by-interest/immigration-executive-actions-under-trump-administration, accessed Sep 28, 2020

Jens M. Krogstad, “Key facts about refugees to the US”, Pew Research Center, Oct 7, 2019, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/10/07/key-facts-about-refugees-to-the-u-s/, accessed Jul 6, 2020

Nick Cumming-Bruce, “Number of People Fleeing Conflict is Highest Since World War II, U.N. Says”, New York Times, Jun 19, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/19/world/refugees-record-un.html, accessed Jul 7, 2020

Justice for Immigrants, “Questions and Answers Concerning Proclamation 9983”, https://justiceforimmigrants.org/what-we-are-working-on/refugees/questions-and-answers-concerning-proclamation-9983/, accessed Sep 28, 2020

Jorge Loweree, Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, Walter Ewing, “The Impact of COVID-19 on Noncitizens and Across the U.S. Immigration System”, American Immigration Council, May 27, 2020, https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/impact-covid-19-us-immigration-system, accessed Sep 28, 2020

Credits

Related Problems: Immigration, Income & Wealth Inequality

Authors: George Linzer, Sophia Guan

Reviewed: Adina Langer of the Museum of History and Holocaust Education

Published: December 29, 2020

Feature image: Liberty Island photo D Ramey Logan.jpg from Wikimedia Commons by D Ramey Logan, CC-BY 4.0