Gerrymandering and the Loss of Competitive Elections

Gerrymandering, closed primaries, and sore loser laws, long-accepted practices in American politics that restrict election competition, have new and dangerous implications at a time when our politics are threatened by an authoritarian movement. Such practices now make it possible for Republicans to legally seize and control much of the nation’s political power, as their actions indicate is their intention. As illustrated by the efforts of Newt Gingrich’s GOPAC, this is something that authoritarians on the right have understood for years. They have followed a long-term strategy and are now in a position to dictate election rules and outcomes in most states.

Yet, Democrats and democratically-principled Republicans are the ones who created the opportunity for this crisis to emerge.

Election competitiveness remains low, and in 2020 was below average for even year elections since 2010. According to Ballotpedia, roughly 35% of state legislative districts in 2020 saw no competition between the two major parties — in other words, there was not both a Republican and Democratic candidate running. As partisan competition has diminished, elected officials have had less incentive to balance competing constituent needs or find compromise solutions, allowing more extreme views to hold sway.

In a 2017 paper for the Harvard Business School, Why Competition in the Politics Industry is Failing America, former Gehl Foods CEO and policy adviser Katherine M. Gehl and business expert Michael E. Porter contend, “The problem is not Democrats or Republicans…. The problem is not the existence of parties, per se, or that there are two major parties. The real problem is the nature of political competition that the current duopoly has created, their failure to deliver solutions that work, and the artificial barriers that are preventing new competition that might better serve the public interest.”

Gehl and Porter concluded that, despite the good intentions of individual politicians, the two dominant parties have rigged the system through gerrymandered districts that virtually guarantee victory to one party, and through caucuses, primaries, and other ballot access rules that have further reduced the influence of independent voters. As of July 2021, more than 30 million voters had registered as independent or nonpartisan in the 31 US states and territories that permit voters to indicate partisan affiliation, yet both parties have continued to support partisan rules that negate the independent vote.

Back in 2011, two senior fellows at Brookings Institute, Thomas Mann and William Galston, reached a similar conclusion. They wrote that redistricting’s biggest impact was the opportunity it gave to extreme candidates on the left and the right, who are most capable of getting their base of supporters out to vote.

“Considered in tandem with low-turnout primaries, gerrymandering further diminishes the influence of moderates”, they concluded.

“Being Primaried”

“My only task was to win a closed Republican primary, as the general election was a foregone conclusion in my district. That required that I favor the partisans in my own party in order to be elected and stay in office. Across the country, people who want to run for office from both parties must swear allegiance to the party platform and a set of partisan principles. Those inclined to collaborate across the aisle are susceptible to primary challenges. Ask any elected official honest enough to speak the truth. Most politicians in America today worry about one thing above all others. Being primaried. It confines us, limits us and restrains our ability to work for our districts.”

– David Holt, an Oklahoma state senator from 2010-18 and mayor of Oklahoma City since 2018

Gerrymandered Districts

The Constitution requires the federal government to conduct a census at the start of each decade so that seats in the House can be apportioned to the states based on the size of their population. Since a series of Supreme Court decisions in the 1960s that led to the requirement that political districts in each state be of equal population, states have used census data to redraw their political district lines accordingly. In most states, redistricting is done through the normal legislative process, which often means one of the parties has the power to dictate the district lines.

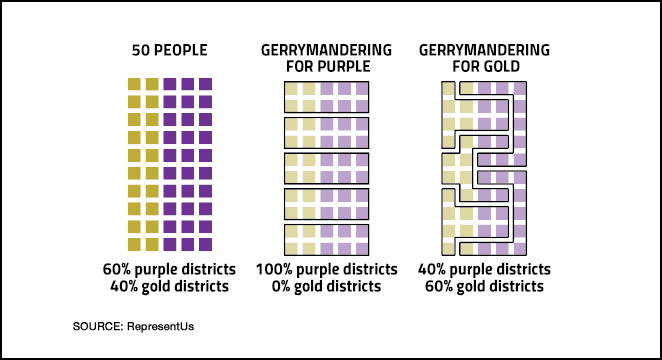

This long-used practice is called partisan gerrymandering. It describes a process in which a state is divided into political districts designed to create legislative and congressional “safe seats” that enable the controlling party to maximize and preserve its hold on power. Both parties are guilty of this practice, but after the 2010 election Republicans were in a better position to turn redistricting to their favor.

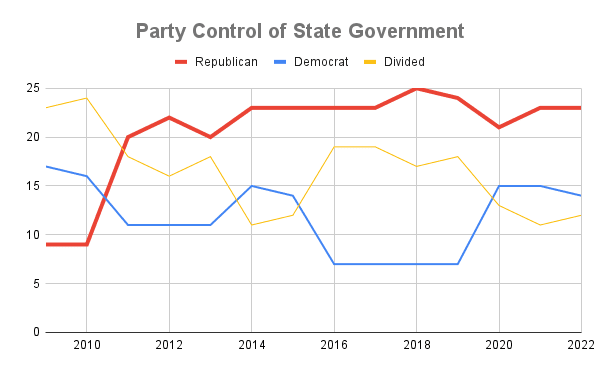

While gerrymandering of congressional districts gets much of the attention, its impact is as important at the state level. Party control of state government shifted dramatically between January 2010 and January 2011 as Tea Party Republicans swept into office. In 2010, Republicans controlled the governorship and both halves of the legislature in 9 states; that number was 20 a year later. As of February 2022, Republicans had such a “trifecta” in 23 states, while Democrats had such control in 14 states.

At the federal level, a 2017 Brennan Center for Justice report on extreme maps found that gerrymandering after 2010 provided Republicans with a built-in advantage of 16 or 17 seats in the House of Representatives. Yet, a New York Times analysis of the new congressional district maps drawn following the 2020 census indicates current partisan parity among districts nationwide. This news is not something to celebrate, however. A more nuanced assessment shows Republicans hold a lead in districts that are more solidly partisan, 186 to 167. That means that 81% of House seats are not competitive and moderate candidates are more likely to face primary opposition from partisan extremists.

What Redistricting Looks Like

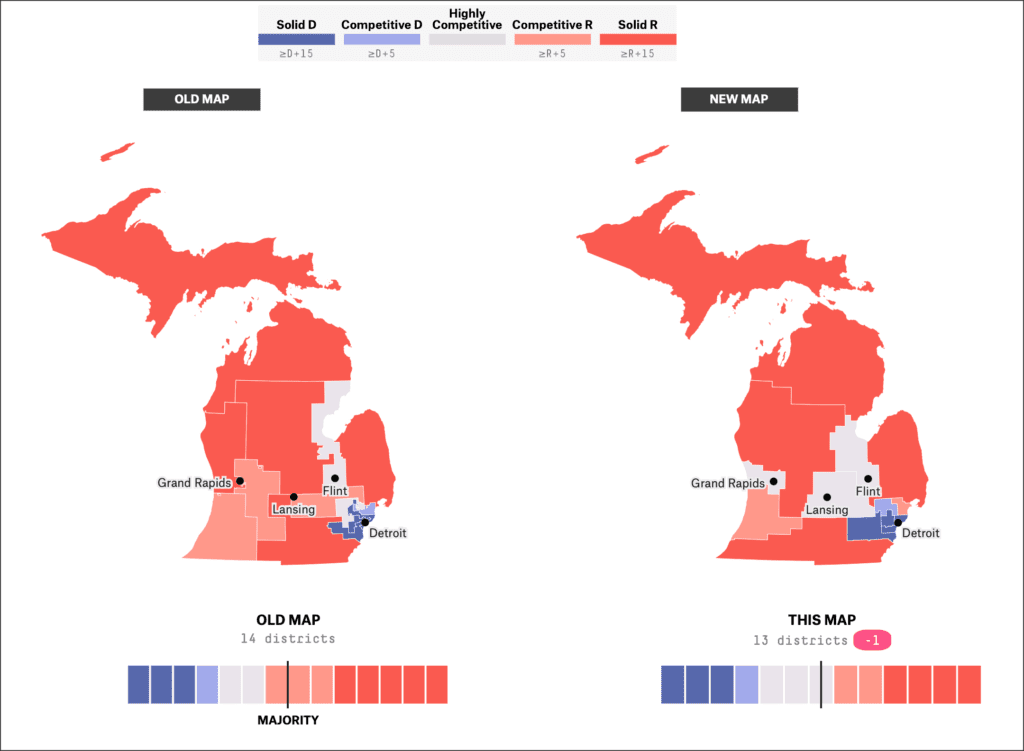

The news site, FiveThirtyEight, has an updated tracker that provides a look at redistricting in every state. The maps below illustrate the impact of Michigan’s new redistricting process. The old map reflects the gerrymandered districts drawn by a Republican trifecta following the 2010 census; the new map is the product of the new independent redistricting commission created by a 2018 ballot initiative.

Primaries and Caucuses

Primaries and caucuses are used by the two major parties to nominate almost all candidates for elective office. The rules governing them can change by party and from state to state, but in 23 states’ presidential nominating contests and 15 states’ congressional nominating contests, at least one party holds closed primaries, and in a few states, at least one party still chooses their presidential nominee through a caucus. These selection processes exclude independent voters and less enthusiastic party members.

Primaries take one of several basic forms. Closed primaries only allow registered party members to vote in them. In those states with closed primaries, nonpartisan independents, also known as unaffiliated voters, have no say in who appears on the general election ballot. This means that in heavily gerrymandered districts, where the winner of the favored party’s primary is almost certain to win the general election, independent voters have virtually no voice in who represents them.

Semi-closed and semi-open primaries allow unaffiliated voters to participate, though in some states they must register with the party whose primary they choose to vote in. Only in truly open primaries can any registered voter participate regardless of party affiliation.

Caucuses are an older and less costly nominating alternative. They are also more exclusionary and are used now in only a handful of states and US territories. While primaries simply require voters to cast a ballot, similar to the general election, caucuses may ask voters to spend hours at a polling location, where they engage in conversations with other voters from their communities and, in some cases, physically move around the room for several rounds of balloting. This may sound like a more deliberative form of democracy, but it leaves out potential voters who are unable to take multiple hours out of their day to vote due to work, responsibilities at home, or any number of other barriers.

Generally, only the most enthusiastic and — often — partisan voters participate in a caucus.

Sore Loser Laws

In 47 states, a candidate who loses a primary cannot appear on the general election ballot by running as an independent or affiliating with another party. These states either have a law explicitly prohibiting a primary election loser from being included, or they create rules, such as early registration deadlines, that have the same effect. Such laws can work against more moderate candidates who have broad support.

Two examples from 2010 illustrate the point. Mike Castle, a centrist elected nine times as Delaware’s sole representative after serving two terms as governor, was heavily favored to win an open Senate seat. Yet, he was defeated by the more partisan Tea Party candidate in the Republican primary, in part because of low turnout. His long history of statewide victories suggested he would have had a solid chance of winning in November had he been allowed to run as an independent. But state law prohibited him from appearing on the general election ballot, and the seat went to Democrat Chris Coons.

The same year, eight-year incumbent senator Lisa Murkowski was defeated in the Republican primary in Alaska by another Tea Party candidate. State law said her name could not appear on the general election ballot. But she nonetheless won re-election as a write-in candidate, the first senator elected that way since 1954.