The takeover of the Republican Party by anti-democracy extremists and the intra-party friction it generated, on full display in the House of Representatives’ battles over the House speakership this year, has been the big political story of this century. Only now is the story beginning to get the coverage it deserves. In the coming months and years, we will learn if it is too little too late.

For much of the last 30 years, the narrative that dominated the news media’s political coverage over-emphasized the animosity and divide between Republicans and Democrats. That the roots of this narrative lay in the Newt Gingrich-led efforts to train the next generation of Republicans to vilify their Democratic opponents is an essential part of a story that was mostly ignored at first and then obscured in more recent years by Donald Trump’s takeover of the party. It was Gingrich’s strategy – embraced by the Republican Party – to express anything Republican as righteous patriotism and anything Democratic as un-American evil.

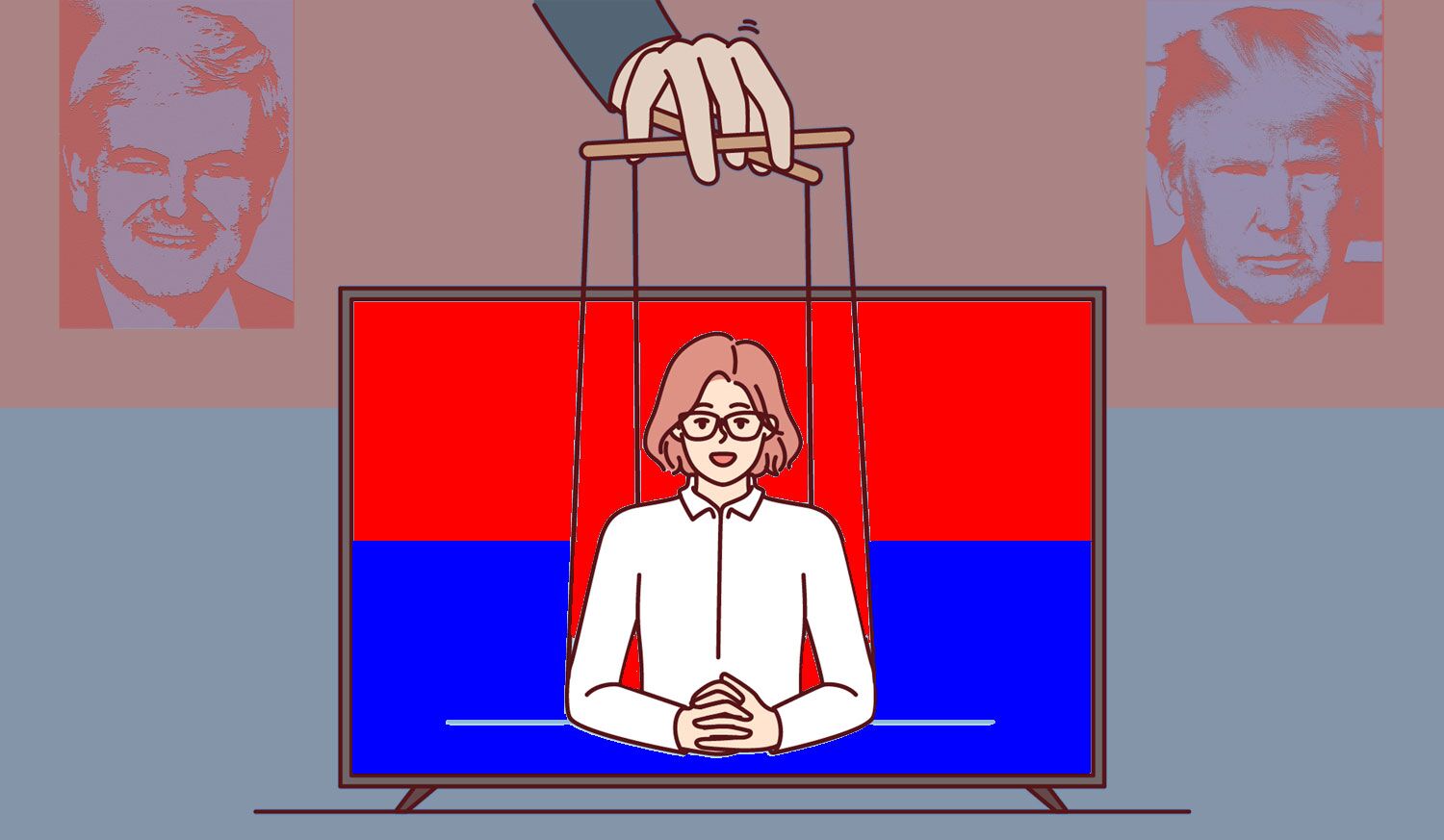

The news media’s adoption of the divisive storyline, particularly in the form of the red-blue paradigm that became the shorthand for our national politics, normalized inflammatory rhetoric that played to the headlines and gave cover to the extremists who now dominate the GOP. As the red-blue divide became central to the public’s understanding of our nation’s politics, the easier it became to overlook opposition from within the party to its growing disregard for the rules and objectives of governing. (This normalization process is similar to what Republican Liz Cheney described to John Dickerson on CBS Sunday Morning on December 3.)

Why is this important now? Because we need to acknowledge the role journalism has played in shaping the events of today in order for the profession to better serve the public tomorrow. And because, in a world where politics is increasingly seen as a narrative battle, everyone – and especially journalists – need to recognize that when we publish a story or consume it, we become part of the narrative.

Paul Farhi of The Washington Post was among the first to recognize how misleading the new color war was. On election day 2004, he explored how the red-blue paradigm came to be “more than just the conveniently contrasting colors of TV graphics. They’ve become shorthand for an entire sociopolitical worldview.” That worldview was defined, he wrote, by caricatures: red for the wholesomeness of NASCAR, church, and country music; blue for the sins of city life, latte drinking, and rock-and-roll. These cultural cliches reflected the language Gingrich had urged all Republicans to use when distinguishing themselves from their Democratic opponents.

Farhi questioned the accuracy of the designations, asking if it was fair to call California a blue state even though it had recently elected a Republican governor and approved initiatives to repeal racial preferences and bilingual education. Nor did he think it right to call Ohio a red state when polls suggested that Democratic presidential candidate John Kerry might win the state on that election day. For Farhi, the caricatures that “red” and “blue” brought to mind were superficial and did not reflect the diversity within each party.

Farhi was on to something. More than a decade and a half later, studies have shown a surprising level of agreement among members of both parties – surprising because of the oft-repeated reminder of how divided we are as a nation. One study published in November 2022 by YouGov, a research, data, and analytics company, found that a majority of Democrats and Republicans support the same 100 policies. Another report published in 2020 by the University of Maryland said that majorities of both parties agree on almost 150 issues, “defying conventional wisdom about a polarized electorate”.

More common ground was revealed this year in survey results from Starts With Us, an organization seeking to build a movement that brings recognition to what unites Americans. The survey asked people from both parties if they thought the other side accepted the importance of a set of six values, including “a government that is accountable to the people” and “fair and equal treatment under the law”. The perception of roughly two-thirds of Democrats and Republicans was that the other side did not share those values. Yet, the survey revealed that almost 90% of people from each party consider those values important.

The red-blue divide, it seems, is more in our heads than our hearts.

As we know, Farhi’s critique of the misleading red and blue labels had little impact. Nor did the earliest signs of cracks in Republican unity, apparent in the early 2000s in the writing of David Brock, author of “The Republican Noise Machine”, and Richard Viguerie, considered a “funding father” of the conservative movement. In the conclusion to his 2004 book, “America’s Right Turn”, Viguerie observed that the party’s conservative message of limited government had been “co-opted by my-party-right-or-wrong partisanship”.

Just Words: The Authoritarian Nationalist Freedom Caucus

Journalists still use the term “conservative” to define the authoritarian, Christian Nationalist Freedom Caucus and election-denying officials like the new House speaker, Mike Johnson. That is a mistake that needs to be corrected.

With the red-blue storyline already entrenched in the media, these early warning signs were easy to ignore. However, the Tea Party election victories, the ouster of John Boehner from the speakership, and the creation of the Freedom Caucus were all clear wake up calls that still failed to change the narrative. During and since the Trump presidency, the anti-authoritarian activism of Republicans like those in the Lincoln Project and Bill Kristol’s Defending Democracy Together offer definitive evidence of the real and deepening divide within the party.

The split is now plainly visible as both Cheney and her fellow Republican Adam Kinzinger have lately been making frequent public appearances to warn that a Republican victory in 2024 will be dangerous for American democracy.

The fiasco that is the House speakership has been a train-wreck long in the making, one that threatens the nation so long as extremists hold sway. The selection of Mike Johnson, a leading election denier, should bring no comfort to those who celebrated when Jim Jordan dropped out of consideration. Despite the wreckage, the train will likely continue full speed ahead.

Journalism’s failure to look beyond the performative politics of the GOP normalized this most dangerous shift in our democracy: the steady radicalizing of the nation’s conservative political party to the point where it elevated an opportunistic cult-like figure to the presidency and embraced destructive, authoritarian tactics to claim and hold onto political power.

As the news media struggles to adapt to the Trumpian world in which truth and knowledge are regularly and overtly subverted by unprincipled newsmakers, the lessons to be learned from the misleading red-blue narrative are imperative. Nuanced and accurate reporting and inclusion of relevant historical context, no matter how cumbersome, cannot be sacrificed for the sake of convenience or the desire to break news as it happens. Focusing on how newsmakers’ use the public stage rather than what they say on the stage can more effectively keep the narrative in the journalists’ hands.

Imagine what the country might look like today if the dominant storyline of the last 30 years had emphasized the issues and democratic principles that bind most Americans instead of the partisan caricatures and inflated areas of disagreement that divide us.

Author: George Linzer

Published: December 4, 2023

Feature image: Original artwork created from an illustration by Mikhail Seleznev for iStock and Library of Congress photos

More Viewpoints

Have a Suggestion?

Know a leader? Progress story? Cool tool? Want us to cover a new problem?