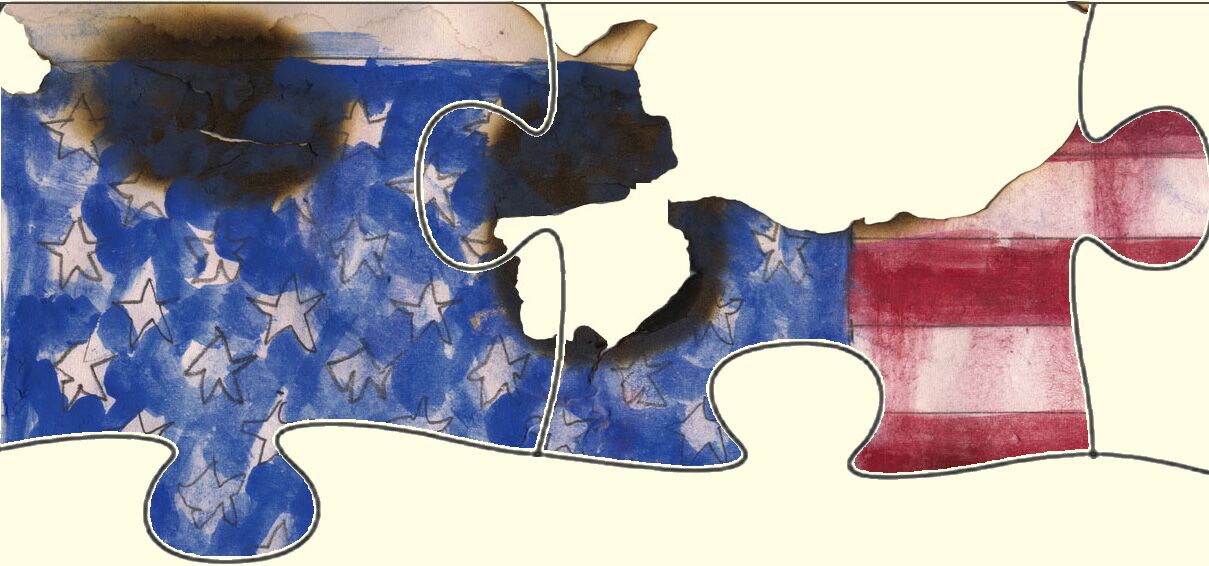

Disinformation and the Loss of Election Integrity

Almost 60% of Americans say they trust the outcome of elections, according to a NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll. While this is worrisome – that means 40% don’t put much trust in elections – the numbers are even more concerning when broken down by party affiliation. Among Republicans, just one-third say they trust election results.

When asked the more specific question, “If your candidate for president does not win in 2024, do you trust that the results are accurate or not?”, only 33% of Republicans said they would trust in the outcome, whereas 82% of Democrats and 68% of Independents said they would.

The cause of this partisan division should come as no surprise. For decades, Republicans have cultivated a mistrust of government and their liberal Democratic opposition and have exaggerated the extent of voter fraud. They have persisted in this disinformation campaign despite numerous studies that have concluded that the extent of fraud perpetrated by both Republicans and Democrats has had a negligible impact on election results. Then, in 2016, campaign operative Roger Stone organized the first “Stop the Steal” campaign, initially to defend Donald Trump’s candidacy in the Republican primaries and then again in the general election against Democrat Hillary Clinton. Even after winning with a decisive 306 electoral votes (albeit only 46% of the popular vote), Trump claimed the election had been rigged against him. It all laid the groundwork for what was to come in the 2020 campaign.

Prior to Election Day 2020, Trump continued to make baseless accusations of fraud and asserted that the only way he could lose was if the election was rigged. Soon after the election was called for Joe Biden, Trump and his allies resurrected the “Stop the Steal” slogan and repeatedly claimed Trump was the rightful winner of an election stolen by the Democratic Party.

The accusation was the extension of a long-term attack strategy in which Republican politicians and commentators employed highly inflammatory terms and ideas to denigrate their Democratic opponents – terms labeling them as anti-child, traitorous, and of course, election thieves. Already reviled and reduced to anti-American, amoral, and corrupt partisans in the eyes of the Republican base, it was clearly not too much of a leap for them to accept the false allegations being repeated by Trump, his supporters in Congress, and the right-wing media.

Gingrich and Seeds of Mistrust

The rise of Newt Gingrich in the late 1980s and early 90s also signaled the rise of a much more aggressive and virulent form of politics that ignored the norms of civil society and openly courted conflict. This was no coincidence. The Georgia congressman rose to prominence by recruiting and educating a whole generation of fellow Republican politicians on what language to use and how to pursue an obstructionist approach to governing. As head of GOPAC, a political action committee set up for this purpose, Gingrich regularly sent recruits cassettes and videotapes describing how to “speak like Newt” and encouraging them to adhere to top-down direction on messaging. In 1990, Harper’s Magazine published an excerpt from “Language: A Key Mechanism of Control”, a pamphlet that listed negative terms GOP candidates should memorize and use to contrast themselves with their Democratic opponents, whether or not evidence merited their use.

Over the years, Republicans repeated words and ideas suggesting that Democrats were anti-child (culminating in 2016’s pizzagate and persisting today in irresponsible claims by Senator Josh Hawley that the Democrats’ Supreme Court Justice nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson had let child pornographers “off the hook”), pro-death (falsely accusing Democrats of wanting to establish “death panels” as part of the Affordable Care Act), and corrupt (fruitless investigations of President Clinton and Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton and the “lock her up” chant at the 2016 Republican National Convention). On the other hand, Republicans have portrayed themselves, as instructed, as the party of family values, pro-life principles, and the sole defenders of law and order.

Gingrich, who went on to become the first GOP speaker of the House in 40 years, remains proud of his role as a political disrupter even if this meant the erosion of civil discourse and the workings of democratic government. Halfway through the Trump administration, he told The Atlantic: “The old order is dying. Almost everywhere you have freedom, you have a very deep discontent that the system isn’t working.”

Disinformation to manipulate hearts and minds to oppose all who affiliate with the Democratic Party is not solely responsible for the erosion of election integrity. American political history is filled with examples of machine politics from both sides of the aisle exerting undemocratic influences on the selection of candidates, competitiveness of general elections (see Gerrymandering), and who is able to vote (see Voter Suppression). Here are two recent examples:

- The Republican claim of election fraud with regard to the use of absentee ballots proved true in 2018 in North Carolina’s 9th Congressional District, and in particular, Bladen County. Republicans themselves perpetrated the fraud that assured Mark Harris’ initial victory in November. But in February 2019, after substantial evidence of fraud was presented during hearings, the State Board of Elections called for a new election. Days later, Harris dropped out of the race.A study published in Election Law Journal suggested a pattern of “anomalous mail-in absentee voting” in Bladen County in the 2018 Republican primary and in the 2016 general election.

- In 2016, Sen. Bernie Sanders, whose primary challenge to Hillary Clinton rocked the Democratic Party in a way similar to Trump’s impact on the Republican primary, claimed the Democratic National Committee had the capacity to unfairly tilt the nominating process to favor Clinton. His allegation focused on the fact that much of the party elite endorsed Clinton early in the nominating process and many of those same people were also superdelegates – elected and appointed officials who had 15% of the vote at the nominating convention. What made them “super” was their freedom to support anyone they liked, unbound by results of the primaries and caucuses. Sanders and his supporters maintained that no matter how strong a showing he made in those contests, the superdelegates were going to vote for Clinton.The rules governing the nominating process were well-established, so claiming that the process was “rigged” was inaccurate and misleading. Sanders’ claim, like the “stolen election” lament from Trump and his allies, contributed to the growing sense of mistrust among voters. (Notably, in 2018 the DNC significantly downgraded the role of the superdelegates.)