Youngstown v. Sawyer

Following a broad exercise of executive power in a time of war, the Supreme Court put forth a framework limiting the power of the president relative to Congress.

Issue

At the height of the Korean War, members of the United Steelworkers union gave notice of their intention to strike over a contract dispute. Fearing what reduced steel production would mean for the ongoing war effort, President Truman signed an executive order commanding the secretary of commerce to take control of the nation’s steel mills. In essence, this move would have resulted in the temporary nationalization of the steel industry. The unions and the steel companies rejected the president’s action, and their legal challenge was brought to the Supreme Court. There, it was decided that the president did not have the authority to make such a claim. Truman complied with the ruling.

Causes

In 1952, the nation was in the third year of the Korean War. Hoping to stabilize steel production and avoid a labor strike to sustain access to this vital war material, President Truman created the Wage Stabilization Board and passed the Defense Production Act. These initiatives failed to achieve Truman’s objectives.

At the time, the United Steelworkers of America sought a new contract. The steel executives were reluctant to meet their demands to raise wages, especially in light of the President’s price stabilization initiative. By 1952, the Wage Stabilization Board had failed to negotiate a deal between the two parties. Subsequently, the Union called for their members to strike, steel executives decided to shut down the mills, and Truman responded by announcing his plan to force the steel mills to stay open.

Outcome

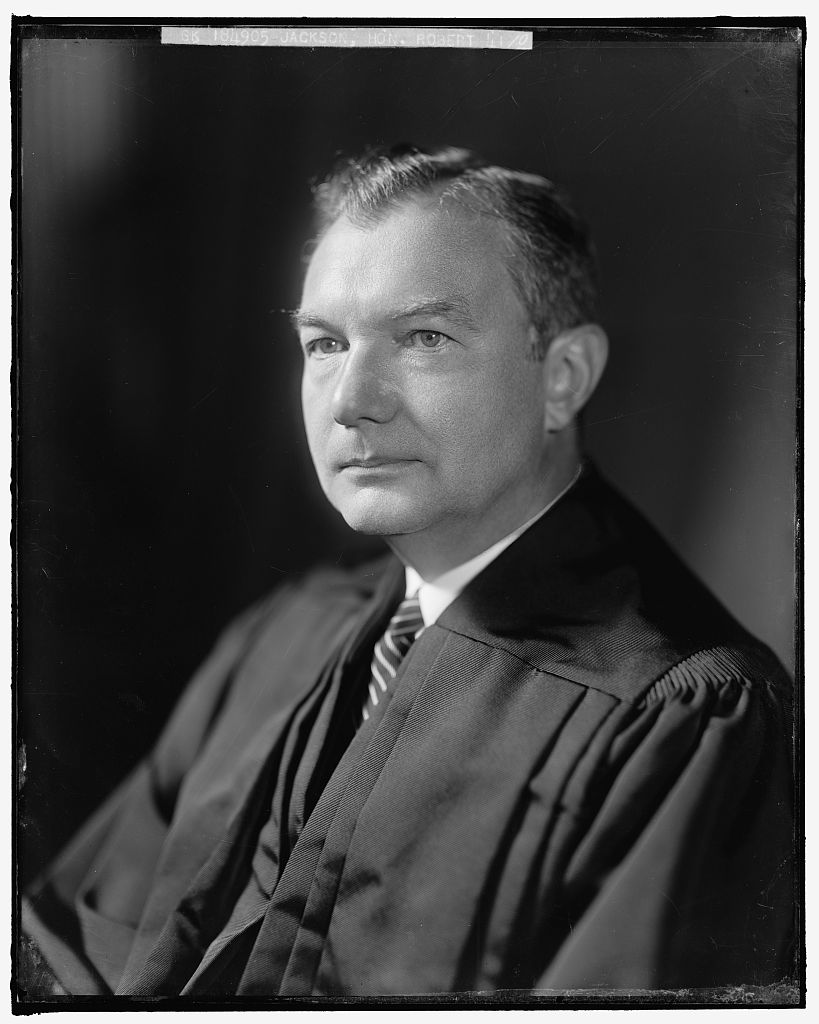

Youngstown v. Sawyer established a legal framework for the limits of executive power used in future cases. Justice Robert H. Jackson’s concurrence with the Court’s decision outlines a three-tiered system which defines the extent of presidential power against the authority of Congress. In short, when a president acts in accordance with a law passed by Congress, the executive wields the combined authority of both branches. When the law is not clear, the president acts in concurrent authority with Congress and the relative extent of the executive’s power depends on the specific circumstances. When acting against the express will of Congress, presidential power is at its lowest. This system has been widely accepted by courts as a tool for ruling on cases in which the executive asserts prerogative powers. The decision affirms that presidential power is both bounded by its relationship to Congress and by the Court’s power of judicial review.

Feature image: Justice Robert H. Jackson, who drafted the three-tiered test of presidential power (Source: Library of Congress)