Roosevelt’s Court Packing Plan

Faced by a Supreme Court that repeatedly struck down New Deal legislation, President Roosevelt attempted to circumvent the Court’s opposition with a proposal to add up to six new, and presumably more sympathetic, justices.

Issue

The US Constitution does not specify how many Supreme Court justices need to be on the bench. In the nation’s first 80 years, the number was changed several times, in part due to westward expansion and for political reasons. The Judiciary Act of 1869, however, set the number of justices to nine, which remained the accepted norm until 1937.

During the Great Depression, when confronted by a Supreme Court that repeatedly struck down elements of his New Deal agenda, President Franklin D. Roosevelt sought to increase the number of justices on the Court so that he could create a majority that would be more sympathetic to his New Deal programs.

Roosevelt proposed a bill titled the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937. Under this bill, a president could appoint an additional justice to the Supreme Court for every justice over 70 years old, up to a maximum of six additional judges. This bill, commonly known as Roosevelt’s Court Packing Plan, was Roosevelt’s attempt to change the political balance of the Court in his favor. Due to the bill’s unpopularity with both Congress and the general public, it was never called to a vote.

Causes

Roosevelt was first elected president in 1932, when the country was in the midst of the Great Depression. To strengthen the economy, Roosevelt enacted a series of New Deal programs that supported unemployed citizens, created new jobs, and reformed the banking system. The New Deal proved to be popular with the public— Roosevelt was re-elected by a landslide in 1936.

Although a majority of the public supported the New Deal, the conservative-leaning Supreme Court opposed it. From May 1935 to June 1936, the Court struck down more pieces of legislation than at any other time in its history. In particular, the Court’s ruling on the case Morehead v. New York ex rel. Tipaldo finally persuaded Roosevelt to take action against the Court. In this case, the Court ruled in a 5-4 decision that it was unconstitutional for New York to set a minimum wage for women and child labor. This ruling worried Roosevelt’s administration, which believed that other New Deal legislation was now under threat.

In an effort to generate more favorable court rulings in the future, Roosevelt proposed the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937. To rally public support for this bill, he spoke about its benefits during his fireside chats, which were a series of radio broadcasts intended to boost the morale of the American people during the Great Depression. During these chats, Roosevelt framed the reform bill as a benefit for the Supreme Court, which he claimed was behind in hearing cases due to the bench’s limited size and the justices’ age.

Outcome

Despite Roosevelt’s high approval rating, only 39% of the public supported the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937. Members of the Senate Judiciary Committee called upon Chief Justice Charles Evan Hughes to testify about the bill. He provided written testimony rebuking Roosevelt’s claim that the bench was behind schedule and explained how increasing the number of justices on the bench would only make the process of ruling on cases slower. The calling of Justice Hughes to testify in Congress exemplified the gravity of Roosevelt’s proposal since justices typically do not involve themselves with legislative affairs. Due to its unpopularity with the public and the Supreme Court, the bill was held up by the Senate Judiciary Committee and was never brought to a vote in Congress.

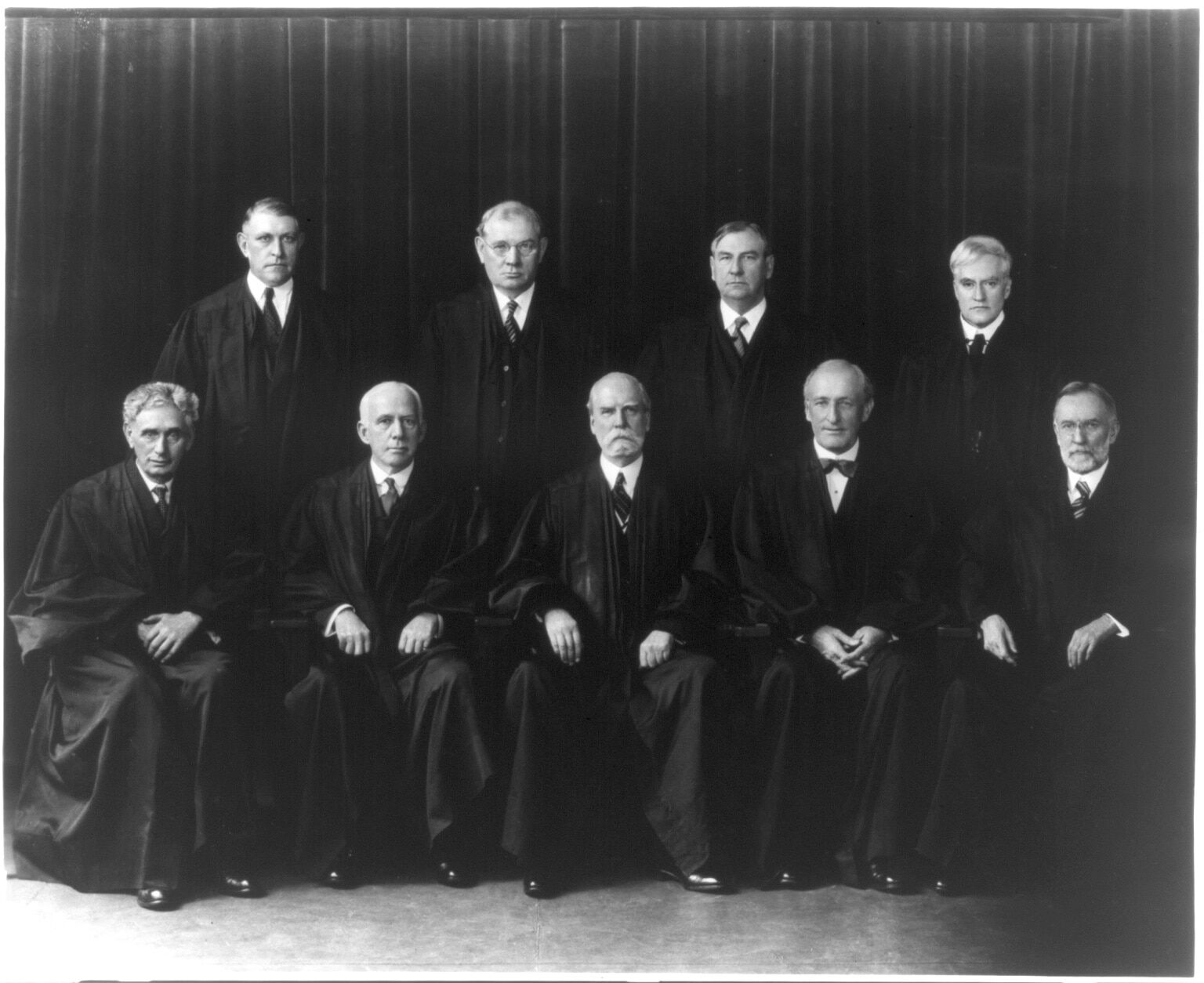

Feature image: Justices of the Supreme Court, 1937 (Source: Library of Congress)