Key Takeaways

- Climate change is already happening, disrupting our lives faster and sooner than many had predicted.

- Many efforts are underway to slow down and halt the warming of the planet and adapt to the changes already happening, but they are generally too small in scale and scope to succeed on their own.

- Without more coordination and urgency from political and business leaders, climate change will generate even greater disruptions to human health and economic and social activity. Even with recent net zero commitments, the world will miss its targets to stop global warming and avert the worsening effects of climate change.

- Our best response to climate change is three-fold: 1) eliminate emissions of greenhouse gases, especially CO2 and methane; 2) remove long-lasting CO2 from the atmosphere; and 3) establish community-level adaptation plans with support from all sectors of the economy and levels of government.

Climate change is happening now, impacting us faster and sooner than predicted. The increasingly frequent floods, wildfires, and extreme weather events are causing damage in a growing number of communities around the country that are just now realizing the meaning of climate change. The specific damage varies by region, but recent reports indicate the costly impacts of climate change are no longer only predictions of the future. Whether or not you believe in climate change, those predictions are now also descriptions of the present.

At a local and more individual level, climate change poses numerous threats to public health and to economic and community security. Warmer northern regions are becoming more hospitable to insects carrying infectious diseases; shortages of water for drinking and farming, already a problem in some areas of the country, are becoming an even greater and more frequent occurrence; droughts and floods are destroying or limiting the growth of some crops, threatening the financial health of farms and affecting what we are able to buy at the grocery store; and warming waters, wildfires, and changing landscapes are killing the marine species and wild game that we fish, hunt, and eat.

Nationally, climate change is a threat to national security as economies are disrupted, rising sea levels threaten military bases, and water and food scarcity within and beyond our borders create tensions over shared resources and the potential for violence and increased migrations of people.

Some state and local governments are taking on some of these climate challenges, as are some companies (where there is a problem for some, there is always an opportunity for others). For those who like to follow the money, Schroders, the global wealth management company, tracks climate change as “a defining theme” of the global economy. Some investors and consumers are putting their dollars to work in support of reducing emissions. Their impact has been surprisingly effective, although they are falling short of important emissions reduction targets. And the government’s National Flood Insurance Program has begun raising premiums in response to unprecedented losses resulting from Hurricane Katrina and Superstorm Sandy, and in anticipation of greater exposure to losses from increased heavy precipitation events and rising sea levels.

Still, the threats of a changing climate have not been acknowledged or accepted by political leaders in all states and localities nor by businesses in key industries like coal, oil, and gas. Without more committed leadership and significant action from business executives and elected officials at the state and federal levels, and in the international community, it is unlikely that the worst effects of climate change will be avoided.

Yet, urgent and coordinated action by the US can still serve as a model and exert positive influence both domestically and internationally.

Problem Definition

Climate change consists of two main problems: human-generated emissions of greenhouse gases that have accelerated global warming, and the changes that global warming is causing to the earth’s climate and the human communities that depend on a stable climate for a steady supply of food and water, secure shelter, commerce, and economic growth.

Emissions of Greenhouse Gases

Accelerated global warming is caused by human-generated emissions of greenhouse gases, especially carbon dioxide and methane. Most attention is given to carbon dioxide (CO2) for two reasons: 1) observations of the rapid increase of CO2 in the atmosphere first alerted scientists to the possibility of global warming; and 2) CO2 lingers in the atmosphere for 300 to 1,000 years, prolonging the greenhouse effect that creates global warming.

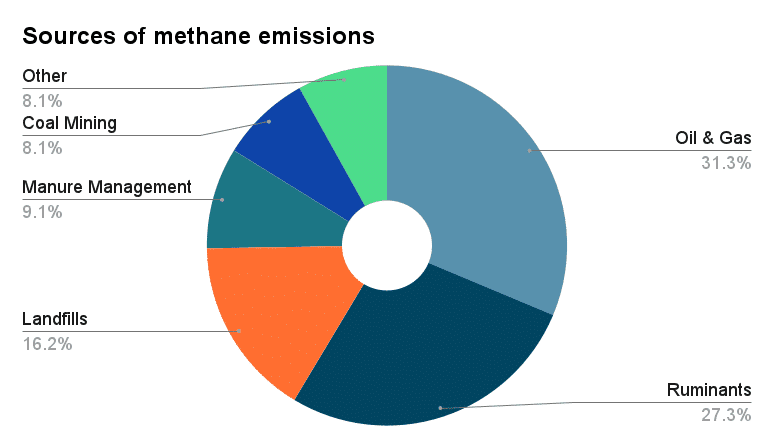

Methane, on the other hand, is a more powerful contributor to warming than CO2 in the first 20 years after emission – about 80% more powerful. So, while CO2’s impact on warming is more cumulative and long-lasting, methane is responsible for 25-30% of today’s warming temperatures.

Disruptive Effects of Global Warming

Global warming has set off a chain reaction of causes-and-effects that is altering weather patterns, changing where fish, animals, and even insects can live, and threatening the safety and livelihoods of millions of people. And that’s just here in the US – the same is happening around the world, causing the US military to view climate change as a threat to our national security and “a threat multiplier” for its potential to magnify existing problems like the spread of infectious disease, human migration, political conflict, and terrorist activity.

At the local level, climate change effects vary by region. In general, weather-related events that cause floods and wildfires and periods of extreme heat have received the most attention in recent years for the ways they can shut down or destroy whole towns and cities. But their impacts can often be felt far away: Smoke from the 2021 wildfires in the northwest led to health alerts warning of poor air quality in the upper midwest and northeast, and California’s drought has meant that many of the state’s almond farmers have watched some of their trees wither and die, contributing to fears of higher prices for almonds and almond products among consumers and market watchers.

Problem Scope

Climate change begins with human-generated emissions of greenhouse gases, especially CO2 and methane, and then follows a series of cause-and-effects in a chain reaction that ripples throughout our cities, towns, and rural communities, affecting jobs, health, and even basic resources like water, food, and shelter. It’s important to remember that what is happening here in the US is also happening throughout the world. Whereas we are currently concerned about the sustainability of repeatedly damaged towns and neighborhoods, entire island-nations are at risk of disappearing under the rising oceans – and their populations will need a new place to settle.

Emissions Sources

CO2

The single largest source of CO2 emissions in the US is the burning of fossil fuels: oil, natural gas, and coal. We burn fossil fuels to produce the energy we need to power our industries, our homes, stores, and offices, and our cars, buses, planes, trains, and other vehicles. In other words, CO2 emissions are associated with almost every aspect of our daily lives. And that’s what makes it so challenging to reduce and eliminate those emissions.

Methane

Scientists estimate that about 60% of the methane in the atmosphere comes from human-related activity. According to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the three most significant sources of human-generated methane emissions in the US are

- Fossil fuels. Methane is emitted during the production, processing, storage, transmission, and distribution of natural gas and the production, refinement, transportation, and storage of crude oil. Coal mining is also a source of methane emissions.

- Domestic livestock. The digestive systems of domestic livestock, especially cows, produce methane that is expelled into the atmosphere. Animals with this kind of digestive system are called ruminants; some ruminants include wildlife like deer and antelope. Because farm animals are raised for human consumption, the methane they generate is attributed to human activity. The storage and management of animal manure results in additional methane emissions.

- Municipal solid waste (MSW) landfills. The bacteria that help decompose waste in landfills generate methane that is released into the atmosphere. Wastewater treatment also generates and releases methane.

Impacts on Our Communities

Costs of Extreme Weather

Within the US, extreme weather events are delivering the first noticeable impacts of climate change. Different parts of the country are experiencing them in different ways. The East and Southeast have seen more frequent power outages and flooding from storms and sea level rise than the West Coast. The western states are experiencing more damaging drought and wildfires. Places like Nashville, Tennessee recently experienced crippling rain “bombs”, tornadoes, and derechos in a 12-month span while other communities like Lake Oswego, Oregon have suffered from extreme temperatures as high as 113° – a full 30° above average.

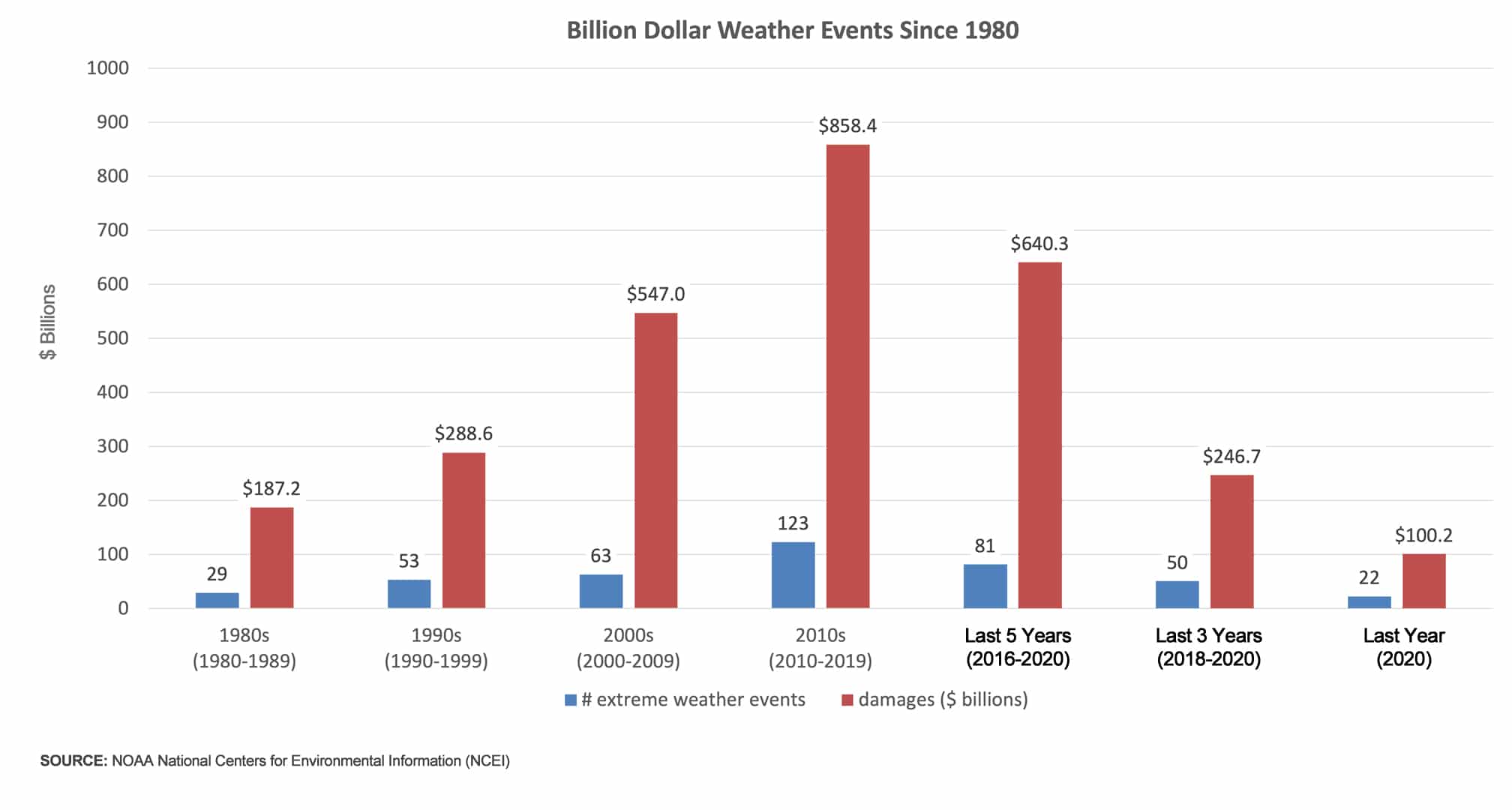

Since 1980, extreme weather events have been occurring more frequently and with greater ferocity than in the past, resulting in more deaths and more costs for recovery. Those costs are typically paid by taxpayers and supplemented by individual donations and the time of countless volunteers. In addition to damages to homes and storefronts, farms and businesses have experienced substantial losses, as have hourly workers whose hours have been curtailed due to extreme heat and fire- and flood-devastation. Few areas of the country have been untouched by unusual or extreme weather.

In 2020, ProPublica, in collaboration with the New York Times, published an analysis of climate data relating to sea level rise, changes in rainfall, heat and humidity increases, wildfires, and the impact of these phenomena on farm crop yields and local economies. The result is a county-by-county assessment of “compounding calamities”. The most-affected county is expected to be Beaufort County, South Carolina while the least-affected would be Lamoille County, Vermont. The analysis includes, for the first time, an examination of the devastating combination of heat and humidity, which can prevent the body from cooling itself by sweating. In 20-40 years, this phenomenon is projected to be felt most in numerous counties in Louisiana and Texas, making outdoor activity in those places dangerous.

Breathing Problems and Spread of Disease

Climate change is also affecting people’s health. In particular, people with respiratory issues will be challenged by increased particulates in the air. And those who spend a lot of time outdoors will be more susceptible to the spread of infectious diseases as disease-carrying insects migrate north with the warmer and wetter climate.

Respiratory illness

Western wildfires triggered air quality alerts and advisories in several western states but also in the upper Midwest, the Mid-Atlantic, and the Northeast. Such warnings are issued when the air has enough particulates, in this case, smoke from fires in the western US and Canada, to cause breathing problems for people with asthma or other respiratory illnesses.

As temperatures rise, ground-level ozone pollution will rise and the pollen season will increase in length. Both could lead to more frequent symptoms and ER visits for people with asthma or other respiratory problems.

In addition, some evidence suggests that dust storms, which doubled in frequency between 1990 and 2000 due to heat and drought, are associated with increased incidents of respiratory illness. In a study of ICUs and dust storms in the US from 2000-2015, researchers found a 4.8% increase in total ICU admissions on the day of the event. When analyzed for respiratory illnesses, researchers found an increase in admissions of 9.2% on the same day.

Infectious disease

Warmer, wetter climates are making northern regions more hospitable for disease-carrying insects (fleas, ticks, mosquitoes), increasing cases of Dengue fever, West Nile virus, and Lyme disease. Cases of diseases carried by ticks, mosquitoes, and fleas tripled in the United States between 2004 to 2016 and are expected to increase further in the decades to come.

In addition, increases in extreme weather events are expected to increase exposure to waterborne and foodborne diseases, affecting food and water safety, according to the US Global Change Research Program. Waterborne and foodborne parasites can transmit illnesses, such as giardia.

Struggles over water rights and usage will intensify

While wetter climates will be more hospitable to disease-carrying insects, drier climates, especially in California and the Southwest, will make existing water problems much worse. The Public Policy Institute of California says that managing water is at the forefront of climate change adaptation in California, with warming temperatures, shrinking snowpack, shorter and more intense wet seasons, more volatile precipitation, and rising seas affecting all aspects of water management. In recent years, California has instituted unprecedented restrictions on water usage, even in the lush agricultural region in the Central Valley.

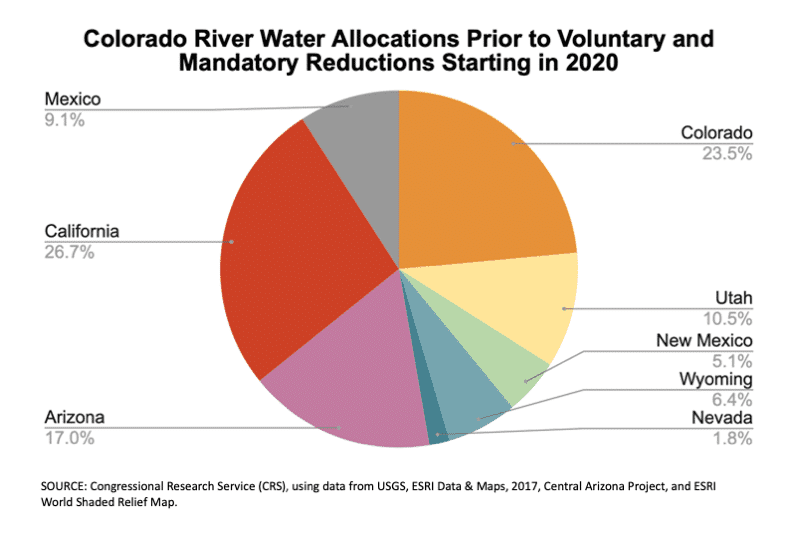

California’s primary source of water, the Colorado River, is in the midst of a prolonged drought that affects the seven states that it serves, as well as Mexico, which is also by legal agreement allocated a portion of the river’s water. Lake Mead, the river system’s largest reservoir, hasn’t been near full capacity since 1999. As of August 2021, the lake was filled to 35% of its capacity and the federal government for the first time had formally declared a water shortage in the Colorado River Basin.

The decreasing water flow has steadily reduced the amount of power being generated by the hydroelectric plant at Hoover Dam and has also forced water conservation efforts in and reduced water allocations to the lower basin states (California, Arizona, Nevada) and Mexico. Due to legal agreements governing water allocations, Arizona has been hardest hit by the reductions in allocations. The state will lose 18% of its allocation in 2022 under the shortage declaration while Nevada will lose 7%. California will not be subjected to a reduced allocation until the water level in Lake Mead drops even further, putting off a reduction possibly until 2023, according to projections.

Limits to What We Know

We Can’t Model What We Don’t Know

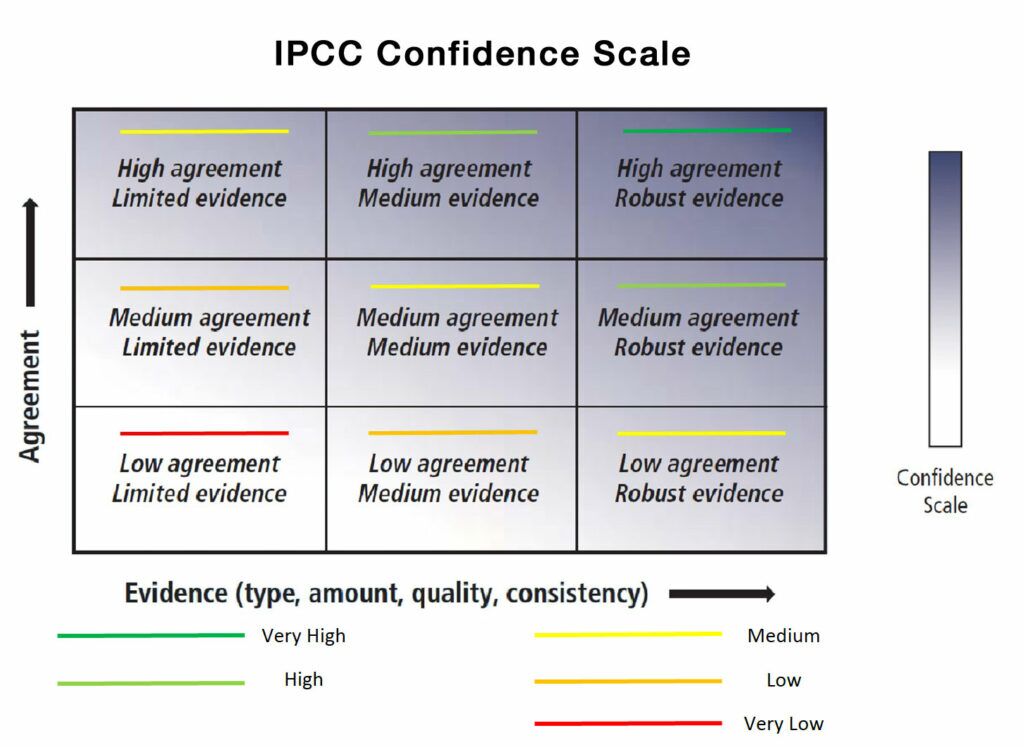

Modeling climate change is a far greater challenge than landing a man on the moon. Climate is a complex interdependent system that we still do not understand completely, and it interacts with our human-built technologies in ways that we can’t always anticipate. And in response to concerns about the quality of the science behind climate change, scientists working with the IPCC have developed a mechanism for qualifying their evidence-based conclusions.

For example, we currently don’t know with 100% certainty that the increase in frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation events is a clear sign of climate change. Such an increase has long been predicted by climate models, so it would seem easy to conclude that this is a definite cause-and-effect. Yet, climate scientists consider the increase as only a “likely” result of human-induced climate change, meaning it has a greater than 66% probability of being true. Given our current state of knowledge, it is not a virtual certainty.

Modeling Our Best Available Knowledge

Climate scientists rely on computer modeling to capture the enormous number of variables that affect our climate and factor into the severity of impacts. These models have steadily become more sophisticated since the IPCC’s first report on climate change in 1990, and they have consistently predicted a rapid warming of the planet. The IPCC, the global body of scientists assembled to review the latest studies and provide policymakers with an updated view of climate change, have published a new comprehensive assessment report every 6-7 years.

Climate models only include what scientists know today to be factors that affect global warming and its effects on climate. When new questions are raised, scientists seek answers and refine the models based on their findings, adding new layers to an already complex set of variables.

Consider Esieh Lake, which sits in Alaska above the Arctic Circle. It is one of eleven lakes studied by scientists because the lakes spew methane into the air from an unexpected geologic source. As reported in the Washington Post in 2018, the prevalence of such lakes can have a significant impact on climate change. The scientists who made this discovery recommended in their study, which appeared in Nature Communications in August 2018, that climate models be updated to incorporate this new finding.

Similarly, other research published in Nature later in 2018 suggests that the Earth’s oceans are warming at a much faster rate than previously anticipated, absorbing as much as 60% more heat since the 1990s than was estimated in older studies. In interpreting the study for its audience, Scientific American noted that as the oceans warm, their ability to absorb carbon dioxide decreases. Because the oceans are warming at a faster rate, they are leaving more CO2 in the atmosphere than scientists had thought, meaning that predictions of global warming made prior to 2018 probably underestimated the rate of warming.

In fact, the IPCC’s most recent 6th Assessment Report (AR6), which was published in August 2021, acknowledges that limiting warming to 1.5°C or 2.0°C above pre-industrial levels – as seemed plausible following publication of AR5 in 2013 – may now be out of reach.

The bottom line is that we can’t model what we don’t know. We can only continue to ask questions where there are gaps or limited data in our understanding, and then support the studies that will strive to answer them.

What We Know and How Sure We Are

Understanding and predicting climate change involves many different kinds of outcomes involving many variables that are known and unknown. Evidence of the past may not be complete or sufficient for ironclad conclusions, and the five models used in AR6 offer little agreement on what the future will look like.

In some cases, an abundance of strong evidence and more agreement within the scientific community leads to more confident predictions. This is why scientists involved with the work reported by the IPCC have been very careful to distinguish the different aspects of climate change by clarifying the likelihood of a particular conclusion and their confidence level in their predictions.

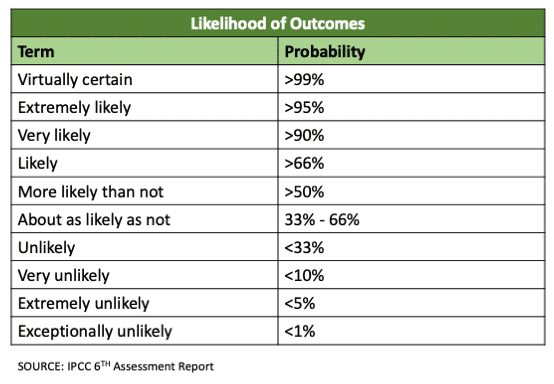

“Confidence” and “likelihood” are the two very distinct terms scientists use to describe the current status of climate change and potential future scenarios. Confidence levels are used to describe a conclusion drawn from soft data and are based on the robustness of the supporting evidence and degree of scientific agreement. The chart below, included in a fact sheet developed by the Australian government, explains the range of confidence found in the IPCC reports.

Unlike the hard-to-quantify findings that prompt use of the confidence scale, the term “likelihood” is used for conclusions that are generated by hard, measurable data and for which statistical probability of occurrence can be calculated. Probabilities are broken into nine categories reflecting ranges of probability, as defined in this next chart.

Examples of “Confidence” and “Likelihood”

The following statements from the IPCC 6th Assessment Report Summary for Policymakers reflect some of the conclusions around the current state of the climate:

- Land and ocean have absorbed a near-constant proportion (globally about 56% per year) of CO2 emissions from human activities over the past six decades, with regional differences (high confidence).

- Human influence was very likely the main driver of these increases [in sea level] since at least 1971.

- Global mean sea level has risen faster since 1900 than over any preceding century in at least the last 3000 years (high confidence).

- It is virtually certain that hot extremes (including heatwaves) have become more frequent and more intense across most land regions since the 1950s, while cold extremes (including cold waves) have become less frequent and less severe, with high confidence that human-induced climate change is the main driver of these changes.

- The frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation events have increased since the 1950s over most land area for which observational data are sufficient for trend analysis (high confidence), and human-induced climate change is likely the main driver.

- Human influence has likely increased the chance of compound extreme events since the 1950s. This includes increases in the frequency of concurrent heatwaves and droughts on the global scale (high confidence); fire weather in some regions of all inhabited continents (medium confidence); and compound flooding in some locations (medium confidence).

NOTE: The summary report section on the current state of the climate begins with this statement: “It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land. Widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and biosphere have occurred”.

The following statements, based on the five scenarios used for AR6 to model future warming, offer some predictions of what we can expect.

- It is very likely that heavy precipitation events will intensify and become more frequent in most regions with additional global warming.

- There is stronger evidence since AR5 that the global water cycle will continue to intensify as global temperatures rise (high confidence), with precipitation and surface water flows projected to become more variable over most land regions within seasons (high confidence) and from year to year (medium confidence).

It is virtually certain that global mean sea level will continue to rise over the 21st century. Relative to 1995-2014, the likely global mean sea level rise by 2100 is as low as 0.28 meters and as high as 1.01 meters, depending on the climate model. Global mean sea level rise above the likely range – approaching 2 m by 2100 and 5 m by 2150 under a very high greenhouse gas emissions scenario (low confidence) – cannot be ruled out due to deep uncertainty in ice sheet processes.

What’s at Stake

Accelerated climate change will continue for decades and possibly centuries, causing disruptions to natural ecosystems and human society. The severity of disruption can vary widely and depends on our success in limiting the magnitude of change and on the vulnerability and adaptive capacity of each community and the natural world. It’s easy to get panicked over worst-case doomsday scenarios but it’s important and even productive to recognize them as real possibilities. It is the first step to understanding the risks, assessing our options, and doing what’s necessary for sustainability.

Economic Stability

As more communities are battered in various ways, and then rebuilt or shrunk, we are beginning to see the diverse impacts of climate change on local and national economic stability. Whole businesses have been wiped out while others choose to relocate, eliminating thousands of jobs and leaving many workers without employment or with lower-paying job options. As jobs and income disappear, so does the tax base that local communities need to provide services, including police and fire rescue.

Some areas on land and in rivers and oceans are becoming increasingly inhospitable to the animals and sea creatures that are hunted and fished for food and profit. Disruptions in the power supply – either knocked out or overwhelmed by extreme weather events, reduced by low water levels around hydroelectric dams, or intentionally shut down due to the risk of wildfire – mean disruptions in productivity as businesses have to close temporarily.

For the most part, local and national markets have failed to prepare quickly enough – or at all – for the economic transitions that lay ahead. One notable exception is found in the market for flood insurance, which is adjusting its premiums to reflect the real risks from increasing frequency and intensity of flood events.

At the global level, the G7 countries, including the United States, partnered with the insurance industry in 2015 on a Climate Risk Insurance Initiative intended to reduce risks, insure losses, and increase resilience, especially among the most vulnerable people and countries. This initiative has made some progress since, announcing in November 2021 the operational launch of the V20 Sustainable Insurance Facility, but it has not yet translated into tangible outcomes. As Munich Re, a reinsurer, noted in 2015:

“There is currently no sign of a ‘silver bullet’. Solutions in the form of … partnerships between governments and the private sector will need to be tested to cushion people against economic shocks resulting from natural catastrophes and help get them out of poverty for good…. [T]he countries concerned will have to have the political will to create the necessary legal, regulatory and organisational conditions.”

Community Survival

Some communities – and those organizations that invest in them – will need to decide whether they rebuild or retreat, particularly those that are repeatedly flooded or threatened and touched by extreme heat, water shortages, and wildfire. New Orleans, which was battered by Hurricane Katrina in 2005, did rebuild and has since survived several intense hurricanes without a repeat of the flooding experienced during Katrina. However, nine years later, the city had just 75% of its pre-Katrina population.

Other smaller and often lower-income communities, damaged by frequent floods or wildfires, have not been so fortunate. As repeated damage or the threat of catastrophe drives people and businesses away, many small towns simply lose the financial capacity to provide the services that hold the community together.

In California where the wildfire season has grown longer and more devastating, some residents who had been lured by the low cost of owning a home in newer communities on the edge of wildland are rethinking their options for where to live. The annual threat of fire, the need to rebuild, and the high cost of insurance weigh on them, but the affordability of such communities remains the magnet that keeps many in place.

Each community must find its own balance between climate-related threats, community strength, and its economic viability as its residents determine whether they should stay or go.

National Security

The Department of Defense (DoD) has issued a series of reports that identify concerns related to climate change. In its 2010 Quadrennial Report, DoD stated that “climate change, energy security, and economic stability are inextricably linked”. The report points out that climate change-related impacts were already being observed around the world, and that intelligence analyses suggested that these changes could lead to further international destabilization.

In its 2014 Climate Change Adaptation Roadmap, DoD warned that without mitigation and adaptation measures, it anticipates a greater need for humanitarian and military action around the world. DoD believes that population centers will experience a steady increase in competition for food, water, and other natural resources, which could also lead to greater human migration and more armed conflicts that may or may not involve US personnel and leadership.

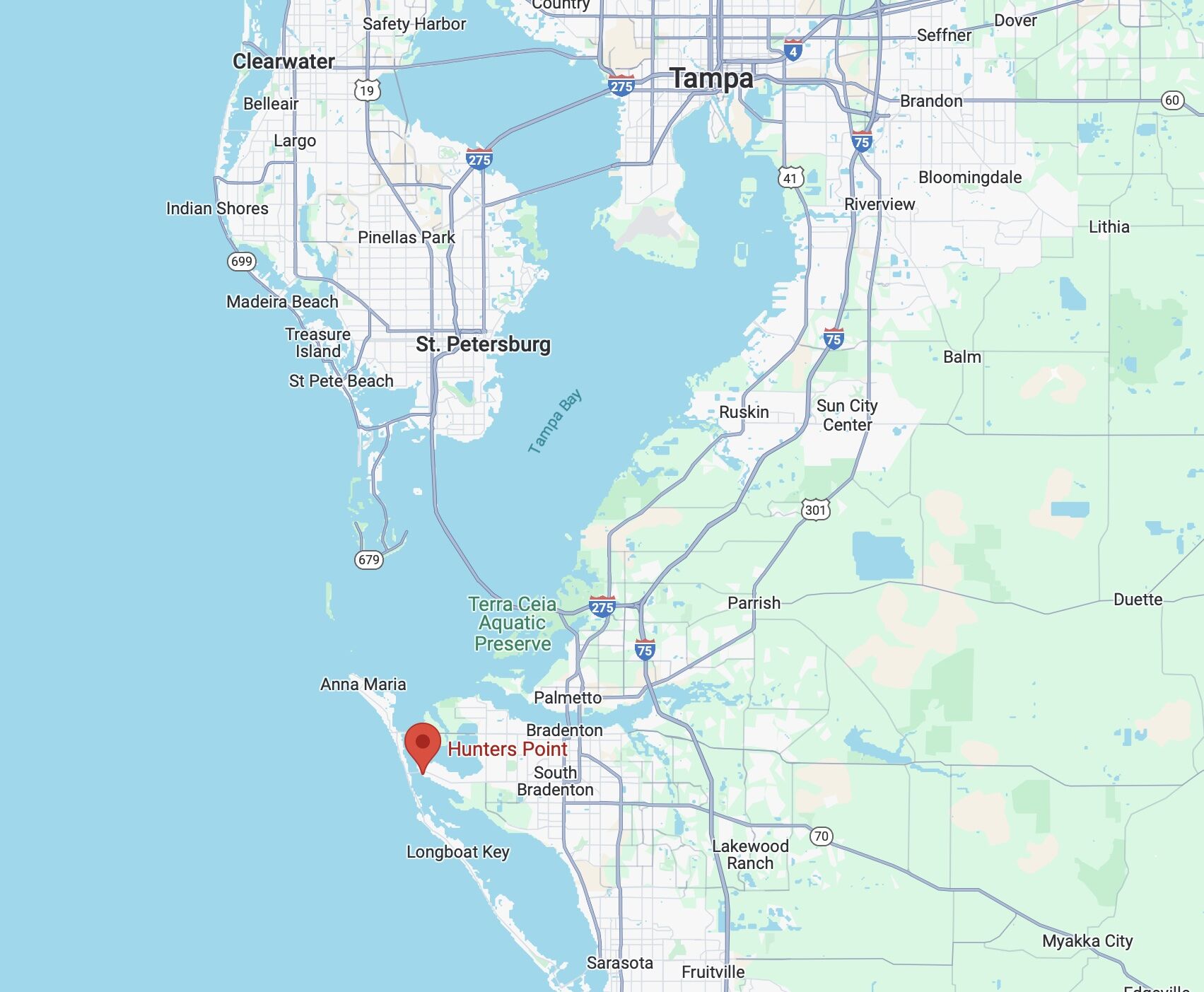

DoD has also expressed concern over the impact of climate change on military facilities and capabilities, noting in particular that, in 2008, the National Intelligence Council determined that more than 30 US military installations faced risks from sea level rise.

These warnings were reiterated in its 2019 Report on Effects of a Changing Climate to the Department of Defense.

Food and Water Resources

US agriculture is vulnerable to climate change. Crops are especially sensitive to heat, drought, and floods. As local temperatures rise and water supplies diminish, crop production will shift north.

The seven-year drought that recently ended in California provides insight into the balancing act required to manage dwindling supplies of water. In California, water use had to be brokered among all citizens for drinking, bathing, and cooking, and for food growers and wineries throughout the state. California agricultural output accounts for 12.5% of the total for all 50 states. In May 2018, Governor Jerry Brown (D) signed two pieces of climate change legislation that set permanent targets for indoor and outdoor water consumption.

In the Southeast, climate change is expected to increase stress over water rights. Georgia, Alabama, and Florida are currently battling through the courts over who gets to use the water in the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint River Basin and the Alabama-Coosa-Tallapoosa River Basin. According to the National Climate Assessment, “Under future climate change, this basin is likely to experience more severe water supply shortages, more frequent emptying of reservoirs, violation of environmental flow requirements (with possible impacts to fisheries at the mouth of the Apalachicola), less energy generation, and more competition for remaining water.” The authors of this section of the report include some climate change adaptation options that should be explored.

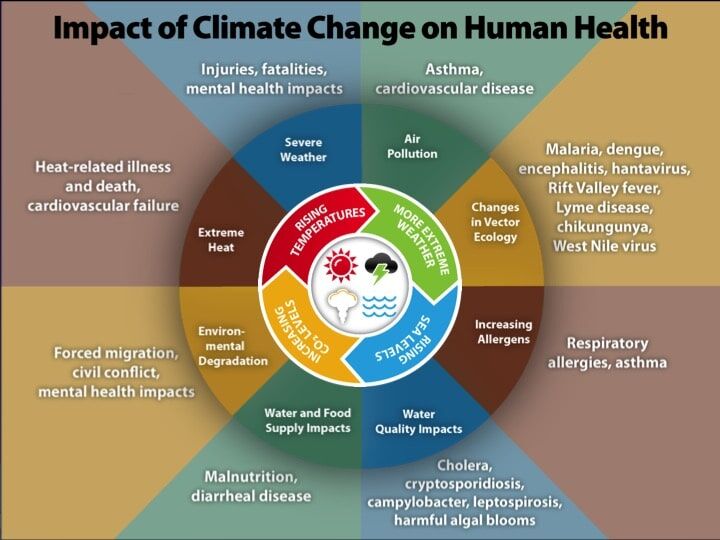

Public Health

Climate change is expected to have several adverse impacts on human health, and will affect specific regions and segments of society differently. The impacts will vary according to the status of public health systems, factors such as wealth and lifestyle, and vulnerable populations in marginalized communities and who currently have the least capacity to adapt.

Similarly, some people will be more affected than others depending on factors like where they live, their age, health status, income, and occupation; and how they go about their day to day lives. People with existing health problems such as heart disease and diabetes are particularly at risk, because drugs used to treat the disease or the disease itself increases sensitivity to heat stress. Currently more than 28 million Americans have heart disease and more than 100 million have diabetes or prediabetes.

While the following health issues will be felt more in poorer countries, we should expect to experience them here in the US as well, even if it is to a lesser extent. Specifically, climate change is expected to result in

- more heat-related deaths and illnesses, especially among vulnerable populations like the elderly and the very young.

- increased deaths and injuries from more frequent wildfires.

- more frequent asthma attacks in people who suffer from asthma, likely due to a longer growing season for ragweed and other pollens.

- increased number of incidents of food-borne and water-borne diseases, and possibly vector-borne diseases like West Nile Virus and Lyme Disease.

Source: Centers for Disease Control

Potential Obstacles

Continued Political Opposition

Despite the conversion of then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R) early in 2019, many long-time opponents of federal environmental regulation and a big federal government continue to deny the validity of climate science or refuse to acknowledge that federal action may be the best option for fixing the problem.

The opposition has steadily shifted over the last 25 years, from outright denial of the science to a grudging acceptance that climate change is happening but not as a result of human activity. In 2014, former deniers tried a different strategy, with multiple politicians claiming “I am not a scientist” to avoid commenting on what was becoming increasingly evident: climate change is real and we are starting to see its effects.

For these opponents, the immediate economic and political impacts of an active climate change policy outweighs their concerns for the long-term disruptions to come. And perhaps more perversely, climate change denial has contributed over the years to the hyperpartisanship that has degraded our politics and emboldened a science-denying, logic-defying authoritarian movement that puts at risk businesses and governments that defy it.

Debates Over Alternative Energies

The burning of fossil fuels is the primary source of greenhouse gas emissions – and also the fuel on which modern society exists. The switch to viable alternative energy sources is imperative if we are to slow and eventually reverse climate change and its effects.

However, debates about the most environmentally pure alternative energies have slowed progress on expanded use of alternatives, as have questions regarding the capacity of specific alternatives to meet the energy demands of the 21st century. To date, all alternatives supported by current technologies – solar, wind, nuclear, and hydro – have known limitations and negative environmental impacts, but all outperform oil and gas when it comes to reducing or eliminating carbon emissions.

Economic Transition

Solutions that do not take into consideration legacy industries and the jobs and communities built around them will meet resistance and hinder a prompt and continuing response. The federal government can play an important role in this transition. It is best positioned to work with lawmakers and businesses to bring change-related opportunities to those communities that have been hardest hit by the decline in industrial markets.

Related Considerations

Environmental Justice

As Renee Cho wrote for the Columbia Climate School, socially and economically disadvantaged Americans live in communities that are more vulnerable to extreme heat and other extreme weather events and the poor air quality resulting from burning of fossil fuels and more frequent and larger wildfires. Mostly this is due to historical failures of lawmakers and real estate developers to consider and respect the well-being of black and immigrant communities. The generally poorer health found in these communities, a result of limited access to healthcare and quality nutrition, overcrowding, and inadequate housing, also contributes to their vulnerability to climate change.

Economic and Technological Leadership

The potential impacts of climate change and the deep concerns of much of the world’s population have created an opportunity for the United States to seize the lead in creating new markets for new technologies and new industries. Innovation and market disruption have historically been two driving characteristics of the nation’s economic strength that have often been aided by federal policies. One need look no further than the creation of the federal highway system and the Internet for two relatively recent examples.

Migration

Climate change is driving migration all over the world. With the increases in extreme weather events, sea level rise, and environmental degradation, climate change is expected to trigger famines, economic disruptions, and violence as tensions rise over more frequent and prolonged lack of basic goods and services.

Currently, reliable estimates of climate-related migration are limited, although some reports have suggested that such migration from Central America into the US has already begun. Forecasting the number of future climate refugees into the US is dependent on a number of factors, including US immigration policies. One estimate, based on assumption of an open borders policy, projects that the number of climate refugees from Mexico and Central American countries will be close to 1.5 million per year by 2050 (up from an estimated 700,000 in 2025).

Climate refugees don’t only come from other countries. Already we are seeing American citizens displaced by floods and wildfires. According to the Urban Institute, 1.2 million Americans were displaced in 2018 by weather-related disasters.

A Coordinated Public-Private, Local-National Response

Climate change will cause economic disruptions whether or not business and government agree to tackle the problem. Already, drought, fires, floods, and warming oceans have disrupted commerce, shut down cities, and destroyed communities. Climate scientists and other public activists have long argued that early action to slow climate change and minimize its impacts will be far less costly in the long term than delayed action.

A coordinated response to climate change from both government and business can make the best of a bad situation. It can effectively address the many challenges of climate change while seizing the business opportunities created by them. As the nation modernizes and adapts to an economy with a greatly reduced carbon footprint, it will also be necessary to support the workers who helped build and sustain the fossil fuel-based economy of the past. It is not just the right thing to do, it is vital to sustaining their trust and the trust of our communities in the direction of the country.

Business, with support from government, can help us to transition to a new carbon-free economy while minimizing the inevitable disruptions of the transition.

Frequently Asked Questions

What’s the difference between climate and weather?

Climate is often confused with isolated weather events, so that, for example, when the temperature in the southern part of the US dips below 30°F some people might question whether global warming is really happening. To help understand misconceptions like this, Dr. J. Marshall Shepherd, President of the American Meteorological Society, used a simple analogy: “Weather is your mood and climate is your personality.”

If climate is the personality of the planet, then it is changing from a relatively calm, familiarly stable, even nurturing persona to a much more moody and destructive persona. While the fields where we once grew our corn and the beaches where we played with our kids might have experienced the occasional heavy rainstorm or hurricane, climate change will generate storms of such ferocity on a more frequent basis that some of those fields and beaches will no longer be available to our children and grandchildren.

How will climate change affect where I live?

County-by-County Assessment. ProPublica, in collaboration with the New York Times, published an analysis of climate data relating to sea level rise, changes in rainfall, heat and humidity increases, wildfires, and the impact of these phenomena on farm crop yields and local economies. The result is a county-by-county assessment of “compounding calamities” based on data acquired prior to September 15, 2020.

Climate Effects on Cities in 2080 interactive map is an application developed by the University of Maryland’s Center for Environmental Science. It includes analysis of urban areas in the US and Canada and maps the expected climate-related impacts for the year 2080 under two scenarios: 1) should there be no change in current policies (captured by the climate model called RCP 8.5) and 2) should relatively realistic mitigation efforts be adopted (captured in the climate model called RCP 4.5).

Climate Hazards in 2050 from Climate Central gives you a look at which hazards will affect individual cities the most in the year 2050. It compares two scenarios: 1) one with no change in current policies (model RCP 8.5), and 2) one that cuts emissions to zero by 2070 (the low-emissions climate model called RCP 2.6).

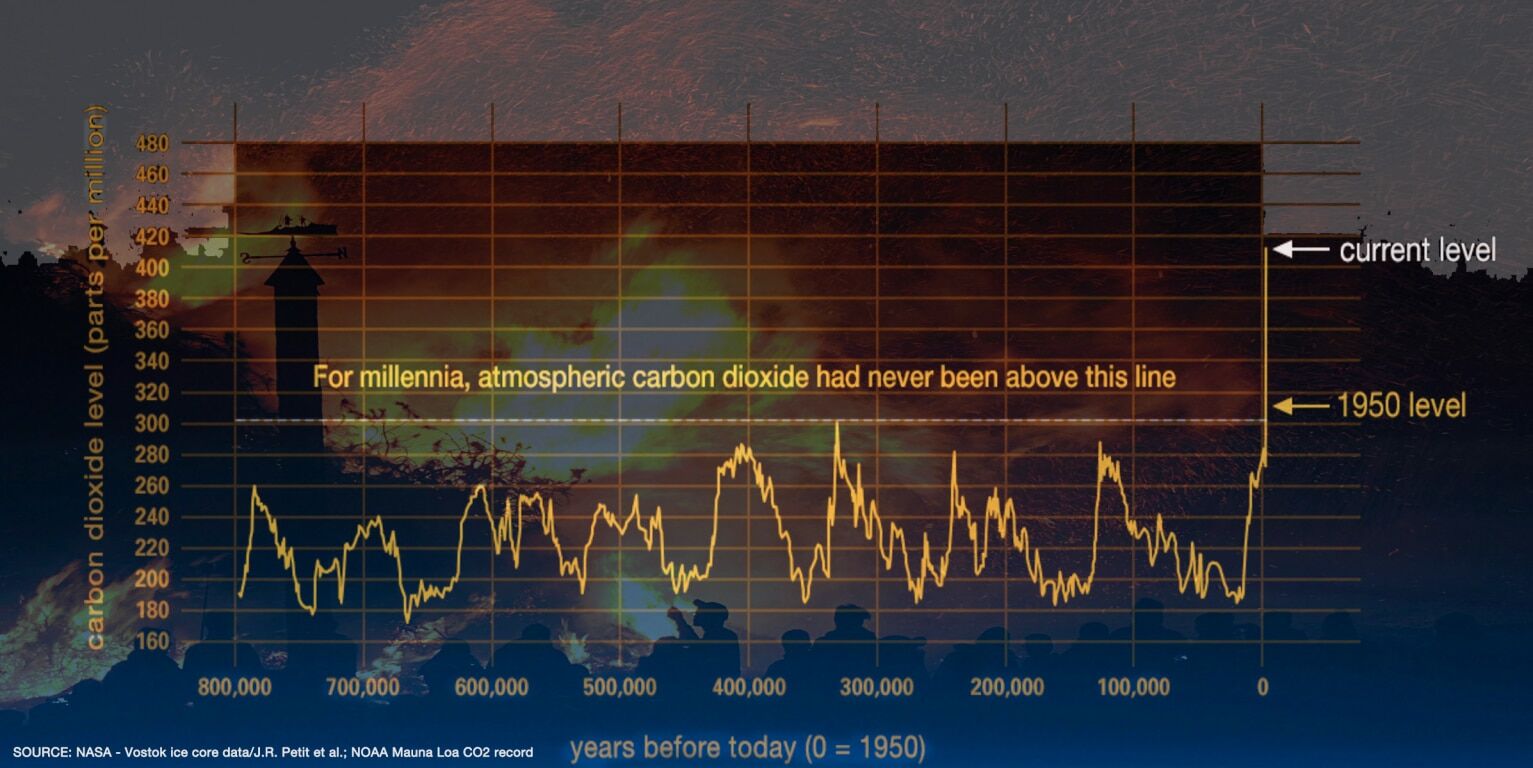

Isn’t “climate change” just a part of the natural cycle of the planet? What makes you think we humans can do anything to change it?

Yes, the Earth goes through periods of warming and cooling, but the rise in global average temperatures since the 1800s is a sharp spike, as revealed in this NASA graph:

That spike closely correlates with the steep increase in man-made emissions of greenhouse gases resulting from industrialization. As western economies developed, and populations worldwide multiplied, more fossil fuels were burned to keep up with rapidly increasing demands for power. The resulting CO2 emissions as well as the increased emissions of methane from industrialized agriculture, both greenhouse gases, produced the accelerated rise in the global average temperature.

The fact that human society had this kind of impact on Earth’s natural cycle once suggests that we have the capability to further affect the system a second time.

Didn’t the same scientists claim we were heading into a new ice age just years before claiming the world was warming? How can we be sure the scientists have it right this time?

First, let’s clarify what the scientists are saying today, and have been saying with increasing confidence over the last 40 years: The earth is experiencing accelerated global warming due to human-generated emissions of greenhouse gases, which are a byproduct of burning the fossil fuels that powered the industrial revolution. Accelerated warming, the scientists further say, is triggering rapid changes in climate that will disrupt, and in some cases, may devastate human economies and natural ecosystems in many, many ways.

As explained under Limits to What We Know, scientists have been very careful to assign a well-defined confidence level to their interpretations of the data available to them. The curse of science is that knowledge is not static; scientists are constantly refining and sometimes redefining their conclusions as new information becomes available. The threat of a coming ice age that made the headlines in the mid-1970s, and that is often cited as evidence against today’s claims of warming by science doubters, was a misinterpretation of incomplete data by a small group of scientists that was then amplified by numerous mainstream media outlets.

As history writer Jack El-Hai has noted, the scientific literature of the 1960s and ‘70s included six times as many peer-reviewed papers warning about global warming as there were papers concluding that the earth was cooling. So even then, a consensus was emerging. The news media, however, made a significant error in reporting on the latter, something that science writer Peter Gwynne, who penned a 1975 Newsweek article, “The Cooling World”, has since acknowledged. In 2009, Washington Post columnist George Will mistakenly cited Gwynne’s article, calling it a Newsweek cover story, as evidence supporting his own skepticism of some of the projections being made about our warming world.

Back to the question about how sure we can be about current claims of global warming and adverse climate change. Science never allows us to be 100% certain, but as any entrepreneur or astronaut or military general or poker player will explain, if the data is sufficiently strong and the statistical odds favor a given course of action, we should act decisively. Today, after decades of refining their understanding of how our climate system works, scientists are highly confident that human-caused climate change will have many adverse consequences for communities across the United States and around the world.

Tools & Resources

The organizations and resources listed below offer different ways to become engaged in the fight to reduce emissions of CO2 and adapt to climate change. Some organizations are not-for-profit, some are advocacy groups, and others are commercial enterprises or government agencies. This list is not even close to being comprehensive, but includes some of the more productive and visionary resources.

Business and Investment Opportunities

Project Drawdown includes a list of 80 solutions ranked by how much CO2 each solution removes from the atmosphere. The list includes abandoned farmland restoration, geothermal power, and water distribution efficiency, and it continues to grow as more solutions are evaluated and added.

Ceres, a sustainability nonprofit, offers a variety of reports, tools, and other resources to educate and inspire investors and corporate leaders to take action on sustainability issues, including climate change.

Climate Progress Dashboard was designed for investors by Schroders, a global asset and wealth management company. It analyzes political change, business and finance, technology solutions, and fossil fuel use (entrenched industry) to compare a range of factors in terms of likely degrees of warming. Schroders believes its clients need to understand the risks and opportunities of climate change and the pace of the transition to a decarbonized world.

Aqueduct from World Resources Institute offers two sets of mapping tools: One that helps companies, investors, governments, and other users understand where and how water risks and opportunities are emerging in the US and around the world. The other measures river flood impacts by urban damage, affected GDP, and affected population at the country, state, and river basin scale.

Conservation X Labs applies technology, entrepreneurship, and open innovation to source, develop, and scale critical solutions to the underlying drivers of climate change and other threats to life on earth. The organization was co-founded by Alex Dehgan, a conservation biologist and former science adviser and chief scientist at the US Agency for International Development (USAID), who worries that the loss of plant and animal species are lost opportunities to discover potentially life-saving medical treatments. By offering prizes to spur innovation and through its own programs, the organization expects to test and bring to market a wide range of creative technology-based solutions.

Institute for Sustainable Communities is a Vermont-based not-for-profit that assists local communities to build resilience to climate-related disruptions. It has programs active in all 50 states.

Civic Engagement

GovTrack.us enables you to track and learn about legislation proposed in Congress, and can also connect you with your US senators and representatives so you can tell them how you feel about the bills that interest you.

VOTE411 was launched by the League of Women Voters Education Fund (LWVEF) in October 2006. It is a one-stop-shop for election-related information, including responses from state and local candidates to specific questions.

Project VoteSmart provides free, factual, unbiased information on candidates and elected officials to all Americans.

Community Engagement

The Climate Reality Project mobilizes at the grassroots to make urgent action on climate change a necessity at every level of society. The Project empowers everyday people to become activists, equipped with the tools, training, and network to fight for solutions and drive change planet-wide. It has established 100 active chapters in the US and mobilized more than 19,000 Climate Reality Leaders in over 150 countries.

In Climate research needs to change to help communities plan for the future, climate scientist Robert Kopp describes an iterative, community-driven model for addressing the impacts of climate change that has its roots in the land-grant universities of the 19th century.

At Home

Solar-Estimate offers a free resource that helps homeowners learn about home solar panels and provides an easy-to-use calculator that determines a general estimate of the savings of a solar installation on their home. Note that to get this estimate, you will need to enter your contact information so that up to four companies can contact you with actual estimates.

Purchasing a hybrid or electric vehicle greatly reduces CO2 emissions and for one car company, this is its primary reason for being. Car and Driver magazine reviewed the top 25 hybrid and electric vehicles in 2018 and lists the base price of each vehicle.

Charity Navigator offered this list of highly rated action and advocacy organizations that support environmental protection and conservation issues. It’s nicely organized and presents budget, program, and historical information on each so you can decide which organization is most worthy of your investment of time and/or money.

eBird and iNaturalist are just two projects that use crowdsourced observations to gather data on birds and other species that is shared with science researchers. The research contributes to our knowledge of species populations and migration patterns and any changes occurring to them.

iMatter was found in 2007 as Kids vs. Global Warming and continues today as a youth-focused activist organization. Its activities now include community awareness projects, speaking engagements, federal lawsuits, and worldwide marches.

Monitor The Scope and Impacts of Climate Change

Climate Change Dashboard from NOAA offers a nifty if somewhat technical overview of different aspects of climate change and current projections. The interactive dashboard provides analyses of such effects as sea level rise, glacier melt, and the warming effect of heat-trapping gases. More detail on each item is a click away.

NASA’s Global Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet monitors key indicators of climate change and explains NASA’s role in providing data that is essential to climate change research.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is the United Nations organization established in 1988 for assessing the science related to climate change.

Sources

The URLs included with the sources below were good links when we published. However, as third party websites are updated over time, some links may be broken. We do not update these broken links. If you are interested in the source, it may be possible to find it by copying and pasting the URL into a search on the Internet Archive Wayback Machine. From the search results, be sure to choose a date from around the time our article was published.

Current update

D.R.Reidmiller, C.W. Avery, D.R. Easterling, K.E. Kunkel, K.L.M. Lewis, T.K. Maycock, and B.C. Stewart (eds.), Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II, U.S. Global Change Research Program, 2018, https://nca2018.globalchange.gov, accessed Nov 4, 2021

NAIC, Climate Change and Risk Disclosure, updated Apr 30, 2018, http://www.naic.org/cipr_topics/topic_climate_risk_disclosure.htm, accessed Mar 7, 2019

NASA, Global Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet, https://climate.nasa.gov/causes/, accessed Mar 5, 2019

Rob Jordan, “Stanford researcher reveals influence of global warming on extreme weather events has been frequently underestimated”, Stanford University, Mar 18, 2020, https://news.stanford.edu/2020/03/18/climate-change-means-extreme-weather-predicted/, accessed Oct 29, 2021

Ed Leefeldt, Amy Danise, “FEMA’S Upcoming Changes Could Cause Flood Insurance To Soar At The Shore”, Forbes, Mar 18, 2021, https://www.forbes.com/advisor/homeowners-insurance/new-fema-flood-insurance-rates/, accessed Dec 29, 2021

Jason Metz, Amy Danise, “Here’s Who Gets Hit Hardest By New FEMA Flood Insurance Rates”, Forbes, Oct 1, 2021, https://www.forbes.com/advisor/homeowners-insurance/fema-flood-insurance-rate-changes/, accessed Dec 29, 2021

Phil Prazan, “FEMA Continues New Flood Insurance Rollout Despite Calls for Delay”, NBC Miami, Nov 15, 2021, https://www.nbcmiami.com/news/local/fema-continues-new-flood-insurance-rollout-despite-calls-for-delay/2620991/, accessed Dec 29, 2021

American Institute of Physics, “The Discovery of Global Warming: Timeline”, Aug 2021, https://history.aip.org/climate/timeline.htm, accessed Nov 1, 2021

Alan Buis, “The Atmosphere: Getting a Handle on Carbon Dioxide”, NASA, Oct 9, 2019, https://climate.nasa.gov/news/2915/the-atmosphere-getting-a-handle-on-carbon-dioxide/, accessed Nov 1, 2021

Environmental Defense Fund, “Methane: A crucial opportunity in the climate fight”, Summer 2021, https://www.edf.org/climate/methane-crucial-opportunity-climate-fight, accessed Nov 1, 2021

UN Environment Program, “Methane emissions are driving climate change. Here’s how to reduce them.”, Aug 20, 2021, https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/methane-emissions-are-driving-climate-change-heres-how-reduce-them, accessed Nov 1, 2021

Department of Defense, Report on Effects of a Changing Climate to the Department of Defense, Jan 10, 2019, https://media.defense.gov/2019/Jan/29/2002084200/-1/-1/1/CLIMATE-CHANGE-REPORT-2019.PDF, accessed Nov 2, 2021

Department of Defense, Climate Change Adaptation Roadmap, Oct 13, 2014, https://www.acq.osd.mil/eie/downloads/CCARprint_wForward_e.pdf, accessed Nov 11, 2016

Corryn Wetzel, “California Drought Hits World’s Top Almond Producer”, Smithsonian Magazine, Aug 18, 2021, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/california-drought-hits-worlds-top-almond-producer-180978470/, Nov 2, 2021

Research and Markets, “Global Dairy Alternatives Market Report 2021: Unstable Prices of Raw Materials are Hampering Market Growth”, May 7, 2021, https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/global-dairy-alternatives-market-report-2021-unstable-prices-of-raw-materials-are-hampering-market-growth-301286601.html, accessed Nov 2, 2021

Grace Kay, “A ‘megadrought’ in California is expected to lead to water shortages for production of everything from avocados to almonds, and could cause prices to rise”, Business Insider, Jun 4, 2021, https://www.businessinsider.com/california-water-shortage-drought-could-cause-farm-food-prices-rise-2021-6, accessed Nov 2, 2021

US Environmental Protection Agency, “Overview of Greenhouse Gases: Methane Emissions”, 2021, https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/overview-greenhouse-gases#methane, accessed Nov 3, 2021

US Environmental Protection Agency, “Basic Information about Landfill Gas”, 2021, https://www.epa.gov/lmop/basic-information-about-landfill-gas, accessed Nov 3, 2021

Ula Chrobak, “The US has more power outages than any other developed country. Here’s why.”, Popular Science, Aug 17, 2020, https://www.popsci.com/story/environment/why-us-lose-power-storms/, accessed Nov 4, 2021

Douglas MacMillan, Will Englund, “Longer, more frequent outages afflict the U.S. power grid as states fail to prepare for climate change”, Washington Post, Oct 24, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2021/10/24/climate-change-power-outages/, accessed Nov 4, 2021

NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), “U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Summary Stats”, Cost data CPI-adjusted, Oct 8, 2021, https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/summary-stats, accessed Nov 4, 2021

Al Shaw, Abrahm Lustgarten, Jeremy W. Goldsmith, “New Climate Maps Show a Transformed United States”, ProPublica, Sep 15, 2020, https://projects.propublica.org/climate-migration/, accessed Nov 4, 2021

Associated Press, “Wildfire smoke triggers air-quality alerts in West, Midwest; crews gain ground on biggest fires”, MarketWatch, Aug 1, 2021, https://www.marketwatch.com/story/wildfire-smoke-triggers-air-quality-alerts-in-west-midwest-crews-gain-ground-on-biggest-fires-01627855147, accessed Nov 4, 2021

Emma Newburger, “Smoke from Western wildfires is harming air quality on the East Coast”, CNBC, Jul 21, 2021, https://www.cnbc.com/2021/07/21/western-wildfire-smoke-reaches-east-coast-hurts-air-quality.html, accessed Nov 4, 2021

Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, “Climate and Health”, 2021, https://www.aafa.org/climate-and-health/, accessed Aug 02, 2021

John Schwartz, “Achoo! Climate Change Lengthening Pollen Season in U.S., Study Shows”, The New York Times, May 15, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/08/climate/climate-change-pollen-season.html, accessed Aug 23, 2021

S. Rublee, C. J. Sorensen, J. Lemery, T. J. Wade, E. A. Sams, E. D. Hilborn, J. L. Crooks, “Associations Between Dust Storms and Intensive Care Unit Admissions in the United States, 2000-2015”, GeoHealth, 4(8), e2020GH000260, Aug 1, 20202, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GH000260, accessed Aug 24, 2021

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Illnesses from Mosquito, Tick, and Flea Bites Increasing in the US”, May 1, 2018, https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2018/p0501-vs-vector-borne.html, accessed Jun 24, 2021

US Global Change Research Program, Fourth National Climate Assessment Vol. II: Report in Brief, 2018, https://nca2018.globalchange.gov/downloads/NCA4_Report-in-Brief.pdf, accessed Nov 4, 2021

Jeffrey Mount, Daniel Swain, Paul Ullrich, “Climate Change and California’s Water”, Public Policy Institute of California, Sep 2019, https://www.ppic.org/publication/climate-change-and-californias-water/, accessed Nov 10, 2021

Michael Carlowicz, Kathryn Hansen, “Lake Mead Drops to a Record Low”, NASA Earth Observatory, Aug 22, 2021, https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/148758/lake-mead-drops-to-a-record-low, accessed Nov 16, 2021

Robert Glennon, “As Colorado River Basin states confront water shortages, it’s time to focus on reducing demand”, The Conversation, Aug 16, 2021, https://theconversation.com/as-colorado-river-basin-states-confront-water-shortages-its-time-to-focus-on-reducing-demand-165646, accessed Nov 16, 2021

The Associated Press, “States That Are Cutting Their Use Of Colorado River Water To Conserve It For Others Get Praise From US Water Chief”, Dec 13, 2019, https://www.cpr.org/2019/12/13/states-that-are-cutting-their-use-of-colorado-river-water-to-conserve-it-for-others-get-praise-from-us-water-chief/, accessed Nov 15, 2021

Jim Robbins, “On the Water-Starved Colorado River, Drought Is the New Normal”, Yale Environment 360, Jan 22, 2019, https://e360.yale.edu/features/on-the-water-starved-colorado-river-drought-is-the-new-normal, accessed Nov 15, 2021

Hoover Dam, “Frequently Asked Questions”, Mar 12, 2015, https://usbr.gov/lc/hooverdam/faqs/riverfaq.html, accessed Nov 15, 2021

Brad Poole, “Feds confirm Colorado River shortage, water-allocation cuts coming in 2022”, Courthouse News Service, Aug 16, 2021, https://www.courthousenews.com/feds-confirm-colorado-river-shortage-water-allocation-cuts-coming-in-2022/, accessed Nov 16, 2021

Congressional Research Service, Management of the Colorado River: Water Allocations, Drought, and the Federal Role, Aug 16, 2021, pg. 8, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45546, accessed Nov 15, 2021

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, “Climate change widespread, rapid, and intensifying”, Aug 9, 2021, https://www.ipcc.ch/2021/08/09/ar6-wg1-20210809-pr/, accessed Dec 17, 2021

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, AR6 Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, Aug 7, 2001, https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/, accessed Nov 2, 2021

The Center for Insurance Policy and Research, The Potential Impact of Climate Change on Insurance Regulation, National Association of Insurance Commissioners, 2008, https://www.naic.org/documents/cipr_potential_impact_climate_change.pdf, accessed Nov 15, 2016

National Association of Insurance Commissioners, “NAIC Assesses, Provides Insight from Insurer Climate Risk Disclosure Survey Data”, Nov 23, 2020, https://content.naic.org/article/news_release_naic_assesses_provides_insight_insurer_climate_risk_disclosure_survey_data.htm, accessed Nov 17, 2021

National Association of Insurance Commissioners, “Flood Insurance/National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP)”, Aug 25, 2021, https://content.naic.org/cipr_topics/topic_flood_insurancenational_flood_insurance_program_nfip.htm, accessed Dec 31, 2021

UN Environment Programme, “G7 Countries, Top Insurers Team Up for Climate Change Resilience”, May 7, 2015, https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/g7-countries-top-insurers-team-climate-change-resilience, accessed Nov 17, 2021

Munich Climate Insurance Initiative, “MCII Contribution to the InsuResilience Global Partnership and V20”, https://climate-insurance.org/projects/mcii-contribution-to-the-g7-initiative-on-climate-risk-insurance/, accessed Nov 17, 2021

Munich Re, “G7 initiative: climate risk insurance to support adaptation to climate change”, May 7, 2015, https://www.munichre.com/site/corporate/get/documents_E-1169133942/mr/assetpool.shared/Documents/0_Corporate_Website/1_The_Group/Focus/Climate-Change/munich-re-g7-initiative-berlin.pdf, downloaded Jul 2, 2018

US Census Bureau, “Facts for Features: Hurricane Katrina 10th Anniversary: Aug. 29, 2015”, Jul 29, 2015, https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2015/cb15-ff16.html, accessed Nov 16, 2021

Christopher Flavelle, “Climate Change Is Bankrupting America’s Small Towns”, The New York Times, Sep 2, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/02/climate/climate-towns-bankruptcy.html, accessed Nov 16, 2021

Jim Carlton, Christine Mai-Duc, “They Moved to Rural California for Affordable Homes. Then the Caldor Fire Destroyed the Town.”, The Wall Street Journal, Nov 6, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/they-moved-to-rural-california-for-affordable-homes-then-the-caldor-fire-destroyed-the-town-11636207202, accessed Nov 16, 2021

Union of Concerned Scientists, “Environmental Impacts of Solar Power”, Mar 5, 2013, https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/environmental-impacts-solar-power#.WviSXtPwbaY, accessed Dec 30, 2021

Renee Cho, “Why Climate Change is an Environmental Justice Issue”, Columbia Climate School, Sep 22, 2020, https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2020/09/22/climate-change-environmental-justice/, accessed Jan 11, 2022

Abrahm Lustgarten, “The Great Climate Migration”, The New York Times, Jul 23, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/23/magazine/climate-migration.html?searchResultPosition=1, accessed Dec 29, 2021

Abrahm Lustgarten, “Climate Change Will Force a New American Migration”, ProPublica, Sep 15, 2020, https://www.propublica.org/article/climate-change-will-force-a-new-american-migration, accessed Dec 29, 2021

Tetsuji Ida, “Climate refugees – the world’s forgotten victims”, World Economic Forum, Jun 18, 2021, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/06/climate-refugees-the-world-s-forgotten-victims/, accessed Dec 30, 2021

Carlos Martin, “Who Are America’s “Climate Migrants,” and Where Will They Go?”, Urban Institute, Oct 22, 2019, https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/who-are-americas-climate-migrants-and-where-will-they-go, accessed Dec 30, 2021

Alex Domash, “Americans are becoming climate migrants before our eyes”, The Guardian, Oct 2, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/oct/02/climate-change-migration-us-wildfires, accessed Dec 30, 2021

2019 publication

National Centers for Environmental Information, “Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Summary Stats”, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association, https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/summary-stats, accessed Mar 7, 2019

The Center for Insurance Policy and Research, “Climate Change”, National Association of Insurance Commissioners, updated Jan 16, 2019, https://content.naic.org/cipr_topics/topic_climate_change.htm, accessed Oct 14, 2019

The Center for Insurance Policy and Research, The Potential Impact of Climate Change on Insurance Regulation, National Association of Insurance Commissioners, 2008, https://www.naic.org/documents/cipr_potential_impact_climate_change.pdf, downloaded Nov 15, 2016

Munich Re, “G7 initiative: climate risk insurance to support adaptation to climate change”, May 7, 2015, https://www.munichre.com/site/corporate/get/documents_E-1169133942/mr/assetpool.shared/Documents/0_Corporate_Website/1_The_Group/Focus/Climate-Change/munich-re-g7-initiative-berlin.pdf, downloaded Jul 2, 2018

NASA, “Global Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet”, https://climate.nasa.gov, accessed Mar 5, 2019

NASA, “The Causes of Climate Change”, https://climate.nasa.gov/causes/, accessed Mar 5, 2019

NASA, “Climate Change: How Do We Know?”, https://climate.nasa.gov/evidence/, accessed Feb 17, 2017

IPCC, Climate Change 2014 Synthesis Report, World Meteorological Organization & United Nations Environmental Programme, 2014, https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/, downloaded Feb 27, 2017

Cody Sullivan, “National Climate Assessment: States and cities are already reducing carbon emissions to save lives and dollars”, Climate.gov, Feb. 5, 2019, https://www.climate.gov/news-features/featured-images/national-climate-assessment-states-and-cities-are-already-reducing, accessed Sep 10, 2019

Jess Nelson, “Sea-Level Rise in Miami-Dade Could Cost $3.2 Billion by 2040”, Miami New Times, Jun 20, 2019, https://www.miaminewtimes.com/news/climate-change-study-says-sea-level-rise-could-cost-miami-dade-32-billion-for-seawall-construction-11201008, accessed Sep 3, 2019

Augusta Dwyer, “Without effective action, planet may be on track for irreversible warming, study shows”, Landscape News, Sep 18, 2018, https://news.globallandscapesforum.org/29907/without-effective-action-planet-may-be-on-track-for-irreversible-warming-study-shows/, accessed Sep 9, 2019

US Dept. of Defense, Quadrennial Defense Review Report, February 2010, https://www.defense.gov/Portals/1/features/defenseReviews/QDR/2014_Quadrennial_Defense_Review.pdf, downloaded Mar 14, 2017

US Dept. of Defense, 2014 Climate Change Adaptation Roadmap, Jun 2014, https://www.acq.osd.mil/eie/downloads/CCARprint_wForward_e.pdf, downloaded Nov 11, 2016

Todd Manley, “California Agriculture – A State of Abundance”, Northern California Water Association, Aug 4 2017, http://www.norcalwater.org/2017/08/04/california-agriculture-a-state-of-abundance/, accessed Sep 21, 2018

Taryn Luna and Alexei Koseff, “Get ready to save water: Permanent California restrictions approved by Gov. Jerry Brown”, Sacramento Bee, May 31, 2018, https://www.sacbee.com/news/politics-government/capitol-alert/article211333594.html, accessed Sep 21, 2018

National Climate Assessment, “A Southeast River Basin Under Stress”, https://nca2014.globalchange.gov/report/regions/southeast/graphics/southeast-river-basin-under-stress, accessed Sep 21 2018.

US Environmental Protection Agency, Climate change indicators in the United States, 2016. fourth edition, EPA 430-R-16-004. www.epa.gov/climate-indicators, accessed Feb 9, 2017

Darren Goode, “GOP’ers new tack on climate science”, Politico, May 30, 2014, https://www.politico.com/story/2014/05/republicans-climate-change-science-107234, accessed Aug 16, 2019

Lauren Markham, “How climate change is pushing Central American migrants to the US”, Apr 6, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/apr/06/us-mexico-immigration-climate-change-migration, accessed Oct 1, 2019

John Podesta, “The climate crisis, migration, and refugees”, Brookings, Jul 25, 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-climate-crisis-migration-and-refugees/, accessed Oct 1, 2019

Silja Klepp, “Climate Change and Migration”, Oxford Research Encyclopedia, Oxford University Press, Apr 2017, https://oxfordre.com/climatescience/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228620.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228620-e-42, accessed May 2019

GAO, Climate Change: Activities of Selected Agencies to Address Potential Impact on Global Migration, Jan 2019, https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/696460.pdf, accessed May 7, 2019.

The Economist, “Many governments could bear more debt. That does not mean they should”, May 16, 2019, https://www.economist.com/leaders/2019/05/16/many-governments-could-bear-more-debt-that-does-not-mean-they-should, accessed Oct 1, 2019

Daniel Blitz, Robert Dugger, “This is the US’s hidden debt problem”, World Economic Forum, Sep 4, 2018, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/09/americas-hidden-debt, accessed Oct 1, 2019

Dr. J. Marshall Shepherd, What You Missed in We the Geeks: “Weather is Your Mood and Climate is Your Personality”, The Obama White House, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2014/01/10/what-you-missed-we-geeks-weather-your-mood-and-climate-your-personality, accessed Mar 6, 2018

Maryam Golnaraghi, “Climate Change and the Insurance Industry: Taking Action as Risk Managers and Investors”, The Geneva Association, Jan 22, 2018, https://www.genevaassociation.org/research-topics/extreme-events-and-climate-risk/research-brief-climate-change-and-insurance-industry, downloaded Sep 10, 2019

Australia Department of the Environment, “Fact Sheet: Confidence and Likelihood in the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report”, https://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/b4ba2892-f126-4c4f-a47e-08ca3767eacf/files/wa-decoding-confidence-and-likelihood-ipcc.pdf, downloaded Feb 17, 2017

UBS, “Climate change strategy”, 2018, Climate change strategy – UBShttps://www.ubs.com › link.0396469056.file › climate-strategy-factsheet, downloaded Sep 12, 2019

Kurt E. Reiman, Gerhard Wagner, et. al., Climate change: Beyond Weather, Jan 2007, downloaded from the web Sep 13, 2019

Dr. Dinah A. Koehler et. al., Climate change: A risk to the global middle class, UBS, Jan 11, 2016, https://www.ubs.com/microsites/climatechange/en/home.html, accessed Oct 14, 2019

Credits

Author: George Linzer

Published: March 2, 2023