| Problem Addressed | Voting Rights; Gerrymandering |

| Solution | Started a county by county campaign to win support for nonpartisan redistricting in Wisconsin |

| Location | Lincoln County, Wisconsin |

| Impact | Local, State |

What he did

Hans Breitenmoser helped build a county-by-county campaign to support nonpartisan redistricting in Wisconsin, which directly led to the governor’s formation of a nonpartisan redistricting commission that will draw new district maps after the 2020 Census.

His story

Hans Breitenmoser, a bustling dairy farmer and local Wisconsin politician, has completed a third year in his battle against gerrymandering. After an unplanned entry into local politics that started a decade ago, he has become the center of a statewide effort to remake the way the state draws the maps that define voting districts.

Governor Tony Evers (D) made that perfectly clear during his State of the State address on January 23 this year. Toward the end of his speech, Evers asked Breitenmoser, who had been invited to sit in the gallery, to stand and be recognized for his work. Then the governor announced the creation of a nonpartisan People’s Maps Commission, finalized through an executive order four days later. The commission would be composed “of the people of our state–not elected officials, not lobbyists, not high-paid consultants.”

Breitenmoser says of that moment, “We have come a very long way…. I think there is a really good chance now that we may get what we want because so many people are working on it.”

Breitenmoser is optimistic even though he understands that the new commission’s existence does not guarantee that a nonpartisan map will be approved in 2021. Other parties may offer other, more partisan maps and it is still the Wisconsin legislature that ultimately has to approve the next redistricting map. There is no legal barrier to prevent the legislature from choosing a more partisan-drawn map. Nevertheless, the bottom line, as he sees it, is that people want more fairly drawn districts, and the legislature will now be held more accountable.

For someone who never sought to be a politician, Breitenmoser is at ease with his central role in Wisconsin’s efforts to end gerrymandering. As the son and namesake of the Swiss immigrant who founded the Wisconsin dairy farm that he now runs, Breitenmoser learned to be a forward-thinking businessman who loves his country. He also absorbed his father’s lesson that people in politics are “full of themselves,” he says. “[Getting into politics] was not something I considered even remotely doing.”

Around 2009, however, he agreed to join the county office of the federal Farm Service Agency (FSA). Many Wisconsin dairy farms had closed down primarily due to consolidation in the industry, and the FSA needed someone to step up to help implement federal farm policies. By 2012, a member of the Lincoln County Board who knew Breitenmoser’s work in land conservation suggested that he run for a seat on the county Board of Supervisors.

Breitenmoser had long observed that the problems in his county tended to fester over time, without attention or action from the state. In particular, he noted that battered roads went unrepaired and schools perennially lacked adequate funding. He saw that state legislators chose to focus their attention instead on providing tax cuts to new businesses. Such measures were leaving him and his fellow citizens with a greater tax burden to make up the lost revenue – and still-needed services remained underfunded. He didn’t yet understand that the gerrymandered districts in his state produced such little progress because their elected representatives, comfortably settled into “safe” seats as a result of partisan redistricting, were no longer accountable to voters.

Still, he hesitated to run for office until his wife, a busy midwife and mother, finally encouraged him to pursue the county position even though it meant taking time away from their farm and family. She reminded him that he could be the one working to solve those problems instead of the person complaining about the politicians who neglected to address them. Her argument pushed Breitenmoser to run and win the seat that he’s kept ever since.

She reminded him that he could be the one working to solve those problems instead of the person complaining about the politicians who neglected to address them.

––Hans Breitenmoser recalled the encouragement of his wife to run for the Lincoln County Board

As a member of the county Administrative and Legislative (A&L) Committee, he became responsible for long-term county planning. By 2017, Breitenmoser had grown frustrated with their lack of progress. “I was starting to understand gerrymandering. I had a better handle on it. The Democratic and Progressive voters could cast more ballots and get less seats at the table, and the light bulb went off for me,” he says.

Around the same time, the Wisconsin Farmers Union, to which he belonged, took a stand against political gerrymandering. The union provided literature and political maps that he studied so that he could further understand the degree to which the state was subject to partisan redistricting. Breitenmoser could now clearly “connect the dots” between gerrymandering and his county’s problems.

Breitenmoser had learned that in 2013 and 2014 a handful of other counties in the state had approved nonbinding resolutions against gerrymandering. Early in 2017, he reached out to other groups around the state that supported nonpartisan redistricting: first to Wisconsin Voices, then Common Cause and Wisconsin Democracy Campaign. Breitenmoser’s emails to these groups asked for advice on what he could do about gerrymandering as a supervisor on the Republican-dominated Lincoln County Board.

He heard back from Matt Rothschild, executive director of the Wisconsin Democracy Campaign, a nonprofit, nonpartisan watchdog that advocates for campaign finance reform and other policies to support true democracy and representation. Rothschild encouraged Breitenmoser to write a resolution against gerrymandering that his county board would support. Breitenmoser studied the resolutions from those other counties, and drafted a nonpartisan redistricting resolution tailored to Lincoln County.

With maps and literature from the Wisconsin Farmers Union, Breitenmoser demonstrated to fellow A&L Committee members that gerrymandering was a specific cause of the county’s perennial problems.

The committee quickly and unanimously passed Breitenmoser’s resolution and soon won support from the full board by a vote of 18 to 4. The vote marked not an end but a beginning, as Breitenmoser then embarked on his three year campaign to encourage more counties in the state to pass a similar resolution.

Breitenmoser received some help from Kara O’Connor, government relations director at the Wisconsin Farmers Union. O’Connor was impressed by the win in the heavily Republican Lincoln County, and helped Breitenmoser write and distribute a press release that highlighted his work as a dairy farmer with a mission.

Around the state, others found the news compelling – conservative Lincoln County, a county that Donald Trump had won by 20 percentage points, had voted in support of a policy that was being promoted by the county’s Democrats. Breitenmoser believes the release would not have generated much attention had it come out of a more progressive area like Dane County, home of the state’s progressive capital city, Madison.

But Breitenmoser recognizes that gerrymandering is in some perverse way a bipartisan issue – that is, one that both parties have used to retain and expand their political power. He acknowledges that in the past, the Democratic Party, to which he belongs, had a chance to establish fair, nonpartisan redistricting and didn’t do so, which he finds shameful. However, right now in Wisconsin “it’s obvious we are gerrymandered spectacularly by the Republican Party,” Breitenmoser concludes.

Citizens Action Organizing Cooperative of North Central Wisconsin, a local chapter of a coalition that fosters economic, environmental, and social justice, began to promote the news. Breitenmoser received calls and emails from other counties asking how he got the resolution passed. Citizens Action members collaborated with him to develop a primer on how to get a county board to pass a fair redistricting resolution. He became the go-to person for advice on friendly persuasion and resolution writing.

Breitenmoser advises counties that want to fight gerrymandering to focus solely on nonpartisan redistricting as the number one solution to the problem. He has worked with a number of progressive groups that have several issues they would like to address, such as better gun control legislation, LGBTQ rights, higher minimum wage, and climate change. He emphasizes that it is best to focus on making sure every voter’s ballot counts so that legislative discussion of those issues will be more representative of the population, just as he did in Lincoln County where he was able to explain to his own board how partisan redistricting was connected to why their roads weren’t being fixed and their schools weren’t being funded adequately.

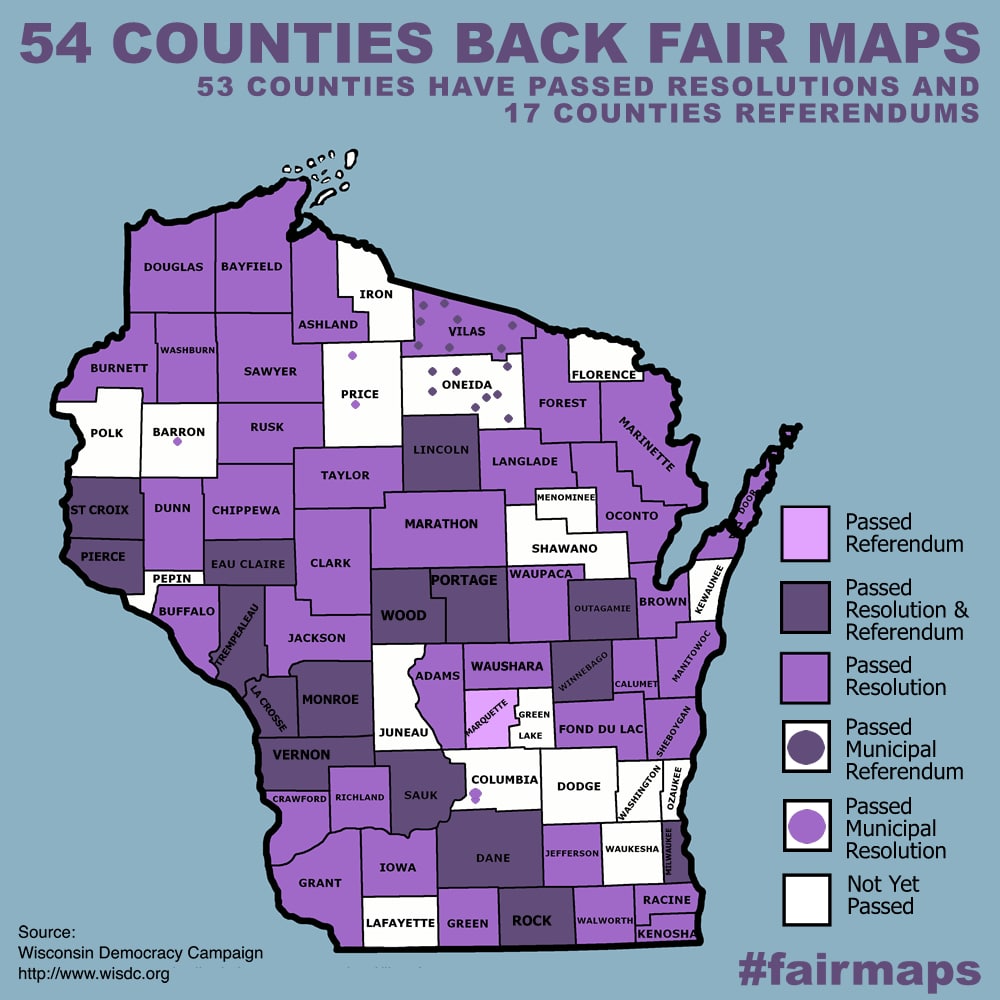

At this writing, 53 out of Wisconsin’s 72 counties have passed nonbinding resolutions, either by vote of the county board or by local ballot referendum in which citizens supported nonpartisan redistricting.

Wisconsin’s approach so far has not changed any laws, but it does give voice to the will of the people who live in the state. Efforts in other states have done the same, as a growing wave of anti-gerrymandering sentiment is sweeping the country. In Michigan, voters passed a ballot initiative in 2018 that called for the creation of an independent redistricting commission to draft district maps. The success of that vote, however, has met with repeated efforts by the party in power to reverse the decision. As recently as July 6, a district court judge dismissed two lawsuits against the creation of an independent commission.

Anti-gerrymandering campaigns have also been launched in Arkansas, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Missouri. Nevada, Oklahoma, and Oregon are working to bring nonpartisan redistricting opportunities to their voters in 2020, according to RepresentUs, a group that fights corruption and supports voting rights.

Iowa has a model that Breitenmoser admires and that he refers to as a good model for Wisconsin. In 1980, Iowa approved a process that involves both the state legislature and an independent commission. The Legislative Services Agency (LSA), composed of nonpartisan civil servants, prepares redistricting plans and is assisted by an independent commission to offer maps to the legislature for a vote. If the legislature rejects the plan, the LSA drafts a second, and if needed, a third mapping plan. If all three LSA offerings are rejected, the legislature must draft and approve its own maps. Since the implementation of this process, the Iowa state legislature has never chosen to reject an LSA proposal.

Breitenmoser knows that anything could happen in 2020, especially given the pandemic and the divisiveness surrounding efforts to expand vote-by-mail during the Wisconsin primary in April. Still, he and his colleagues are looking forward to seeing a fairly drawn and acceptable map next year. Together, they – and Wisconsin’s voters – will be looking for more productive results from the legislature.

Improving Representation

“When elected officials can ignore [the views of 70% and 80% of citizens], folks, something’s wrong.” ––Governor Tony Evers

Interested in learning more about nonpartisan redistricting in Wisconsin? The Wisconsin Democracy Campaign, which advocates for “clean government”, can help.

To learn more about other efforts to end gerrymandering and strengthen voter representation around the country, check out RepresentUs. RepresentUs is an advocacy organization that does a good job of tracking these efforts.

Written by Mary Jane Gore and George Linzer

Published on August 26, 2020

Update on February 26, 2021

Sources

Hans Breitenmoser, telephone interview with Mary Jane Gore, Jun 16, 2020

Ben Meyer, “Evers Highlights Merrill Man In Push For Nonpartisan Map-Drawing”, WXPR, Jan 23, 2020, https://www.wxpr.org/post/evers-highlights-merrill-man-push-nonpartisan-map-drawing#stream/0, accessed Aug 19, 2020

Justin Fox, “A Productivity Revolution is Wiping out (Most) Dairy Farms”, Bloomberg News, Jun 5, 2019, 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2019-06-05/dairy-farms-fall-victim-to-the-productivity-revolution, accessed Aug 2, 2020

Farm Service Agency, Structure and Organization page, undated, https://www.fsa.usda.gov/about-fsa/structure-and-organization/index, accessed Aug 3 2020

Patrick Marley, “‘Dark store’ appeals on the rise in Wisconsin as issue hits ballots this fall, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Aug 28, 2018, https://www.jsonline.com/story/news/politics/elections/2018/08/28/dark-store-appeals-appear-rise-new-study-says/1112775002/, accessed Aug 22, 2020

Politico, “2016 Wisconsin Presidential Election Results”, Dec 13, 2016, https://www.politico.com/2016-election/results/map/president/wisconsin/, accessed Aug 11, 2020

Fair Elections Project, “Fair Maps Coalition”, 2020, https://www.fairelectionsproject.org/fair-maps-wi/, accessed July 7, 2020

Ballotpedia, “Redistricting in Iowa”, 2020, https://ballotpedia.org/Redistricting_in_Iowa, accessed Jul 9, 2020

Craig Gilbert, “New election data highlights the ongoing impact of 2011 GOP redistricting in Wisconsin”, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Dec 6, 2018, https://www.jsonline.com/story/news/blogs/wisconsin-voter/2018/12/06/wisconsin-gerrymandering-data-shows-stark-impact-redistricting/2219092002/, accessed Jul 7, 2020

Have a Suggestion?

Know a leader? Progress story? Cool tool? Want us to cover a new problem?