Controlling the Narrative (1988 – 2004)

While the Reagan Republicans pursued a pro-business agenda that emphasized de-regulation and smaller bipartisan government, Newt Gingrich stepped up his assault on the bonds of inter-party collaboration that kept the federal government functioning. As head of GOPAC, he produced training materials designed to help the next generation of Republican candidates to “speak like Newt”. His goal was to divide the parties not by policy alone but by character as well, using language that suggested only Republicans were patriots and law-abiding citizens.

Working with Frank Luntz, the pollster and rising GOP strategist, Gingrich tapped into the populist anger being stirred by conservative talk radio – the very populism that Kristol warned about. At one point, Luntz brought together a focus group that he said was the most negative, hostile group he’d ever assembled to test the language that ultimately made its way into the Contract with America.

Some years later, Gingrich said of Luntz, “Frank was the first person to understand the scale of radicalism in the middle class. He understands the citizen populist reaction against government in a way that is very helpful.”

As both Gingrich and Luntz knew very well, it’s language that matters most in activating that populist reaction.

Another Republican, Pat Buchanan, added a critical, combustible ingredient to the mix. Following his failed primary bid for the Republican presidential nomination in 1992, Buchanan spoke at the nominating convention and gave a name to the shift in Republican politics, saying that his party was engaged in a “cultural war” – a phrase, soon changed to “culture war”, that appealed to the religious factions of the Reagan coalition and pulled them further into the mainstream of Republican politics.

A Second Warning: “The uncritical embrace of populist anger”

Newt Gingrich and strategist Frank Luntz set out to stoke the flames of anger and fear as they groomed the next generation of Republicans to take down their Democratic opponents. It wasn’t long before the old Reagan Republicans began to voice their unhappiness with where they were taking the party. Bill Kristol, a conservative writer who had served in the Reagan administration, was among the earliest party members to publicly express concern. In a 1994 interview, he told Michael Weisskopf of the Washington Post:

“The danger of uncritical embrace of populist anger is that it’s indiscriminate,” Kristol said. “Many things we should be angry about, but it’s also a great country and Republicans shouldn’t become such a voice for disaffection that we fail to become champions of the greatness and basic health of our society.”

Tea Party Republicans and then Trump and his MAGA supporters became the voice of the disaffected that Kristol worried about. But rather than track the possible rise of extremists in the GOP, Weisskopf and his colleague David Maraniss went on to chronicle what they alleged to be the failure of Gingrich’s revolution. Their reporting made them finalists for a Pulitzer Prize in 1996; it also served as the basis of their book, Tell Newt to Shut Up.

According to the publisher, the book was “an unprecedented, fly-on-the-wall look at the successes, sellouts, and perhaps fatal mistakes of Newt Gingrich’s Republican Revolution…. [It] gets to the heart of the political process.”

With the benefit of hindsight, it is clear the authors misunderstood what was happening, ignored Kristol’s warning, and failed to take a longer view of what Gingrich had started. Kristol went on to launch The Bulwark, an anti-Trump publication, in 2018 and Defend Democracy Together, a never-Trump nonprofit, a year later.

1990

“Language: A Key Mechanism of Control”

As head of GOPAC, Newt Gingrich encouraged GOP candidates to use combative language that drew a stark contrast between Republicans and Democrats as a means of attracting media attention. It was so effective that within 15 years, the red-blue divide had become the narrative framework for discussing American politics.

1992

“A Cultural War”

At the 1992 Republican National Convention, presidential advisor, political commentator, and former presidential candidate Pat Buchanan let the prime time television audience know the country was engaged in “a cultural war”, one rooted in religious beliefs that had no place for abortion rights, gay rights, or equal rights for women.

1994

Unity and Power

Six weeks before the ‘94 midterm elections, House Republicans rolled out the Contract with America, which enabled the party to regain a majority in the House for the first time in 40 years. It was tangible proof that when the party spoke with one voice – when it spoke like Newt – it was stronger and more successful at the polls.

1996

Fox News: GOP-TV

Fox News launched in 1996, bringing to cable television the same combative, populist programming that populated conservative talk radio. It excelled as a megaphone for Republican talking points, soon garnering more than one million viewers a night on its way to becoming the reigning ratings winner among news channels on cable TV.

2000

Voter Fraud: The Little Lie

The controversial presidential election of 2000 brought an intense national spotlight to how elections are run and boosted attention on voter fraud despite little evidence that it was a widespread problem. Nevertheless, this “little lie” persisted and was eventually magnified by Donald Trump.

2002

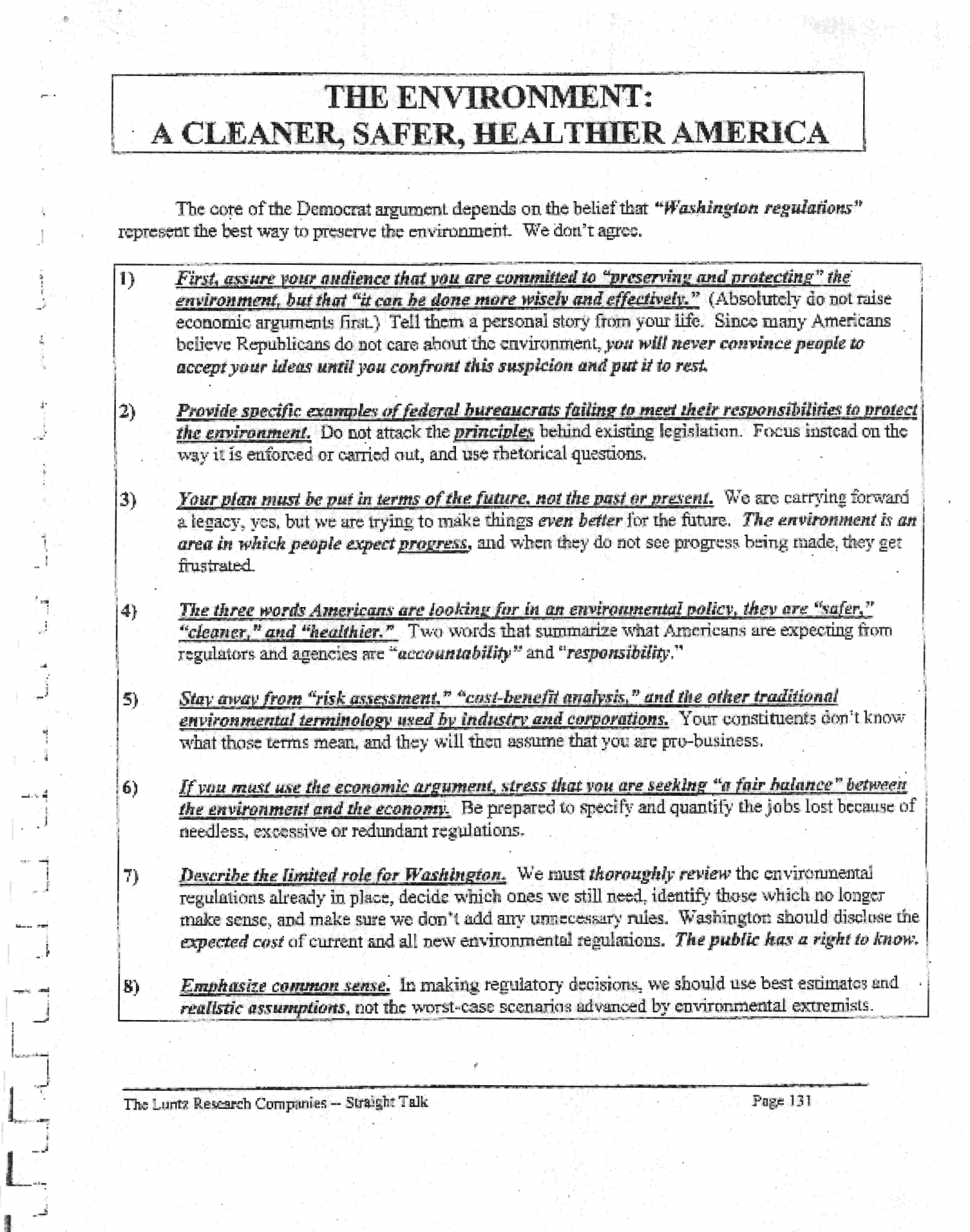

The Luntz Memo: Controlling the Narrative

In a now-infamous memo, GOP advisor Frank Luntz outlined a strategy by which Republicans could seize control of the narrative around climate change. He encouraged them to cast doubt on the science of climate change and to tell stories that would resonate emotionally even if they were factually wrong.

2004

Red-Blue Divide: The Manufactured Narrative

The rhetoric promoted by Gingrich and Luntz struck a nerve outside of the country’s political and economic centers. With Republicans up and down the line following the talking points given them, and conservative talk radio and Fox News and the mainstream media serving as echo chambers, the contrast that Gingrich sought for the culture war took root. The red-blue divide became our national narrative.