Worcester v. Georgia

The anti-Native agenda supported by the president and the legislative branch threatened the nascent doctrine of judicial review.

Issue

In the early 1830s, Georgia asserted its claim to lands near the northwestern corner of the state that were legally recognized as part of the Cherokee Nation. This conflict was brought before the Supreme Court through a lawsuit by Samuel Worcester, a northern missionary working among the Cherokee people who was jailed for his violation of Georgia state law while in Cherokee land. In Worcester v. Georgia, the Marshall Court ruled against Georgia’s claim and found in favor of both the Cherokee Nation’s sovereignty and the release of Worcester. President Jackson, however, was a private supporter of Georgia’s cause and chose not to take action when the State Superior Court refused to enforce the ruling, leaving Georgia’s claims unchallenged and Worcester in prison.

Simultaneously, the president was contemplating how to pressure South Carolina to comply with a controversial federal tariff in what historians call the Nullification Crisis. Fearing that Georgia and South Carolina would find a common cause in their defiance of federal authority and take up arms, Jackson wanted to neutralize the Cherokee issue and so asked the Governor of Georgia to issue Worcester a pardon. Worcester feared the serious threat to the Union that Georgia and South Carolina’s defiance would pose and was no longer convinced that continuing to advocate for the execution of the Court’s decision could secure the sovereignty of the Cherokee Nation in the long term. Consequently, he accepted the pardon.

Causes

In the opening decades of the 19th century, President Jackson and his predecessors led a relentless effort to remove Native Americans from lands east of the Mississippi to make room for White settlers, culminating when Congress passed the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

While working in the Cherokee Nation, Worcester and his fellow missionaries became strong advocates for Native sovereignty. Through his work, he helped establish a Cherokee language newspaper to boost literacy rates and build a stronger sense of national unity. This upset Georgia’s government, which in December of 1830 passed a law mandating that any White man living in Cherokee territory must obtain a special license and take an oath of allegiance to the Georgia Constitution, thereby recognizing the state’s sovereignty over Cherokee land. When Worcester refused to comply, he was thrown in prison, and his subsequent lawsuit against the Georgia government led the Supreme Court to rule on the dispute.

Outcome

Jackson’s defiant response to Worcester v Georgia led Chief Justice John Marshall to write, “I yield slowly and reluctantly to the conviction that our Constitution cannot last.” The Supreme Court’s two decade-old power of judicial review was insufficient to halt the collective will of the president and Congress.

In the nearly two centuries since Worcester, consistent deference to the Supreme Court by the other branches of government has solidified its position as the sole interpreter of the Constitution. Though even today, if a president chooses not to enforce a direct or indirect order delivered by the Supreme Court, the judicial branch would have no power to enforce its decision. The Court’s only recourse would be the hope that its esteem would precipitate enough public and political resistance to force the president’s hand.

Beyond its implications for the balance of power between the Court and the other branches of government, the aftermath of Worcester v Georgia had devastating impacts on indigenous communities. While this case contained strong language in support of Native American sovereignty, Worcester is not considered the ultimate legal authority on this issue. Instead, previous decisions by the Marshall Court as well as subsequent Supreme Court cases tempered Worecster’s language of absolute indigenous sovereignty and created the complex system of quasi-sovereignty that we have today.

Finally, in 1835 President Jackson coerced individual Cherokees to sign a treaty that relocated the entire Nation west of the Mississippi, circumventing Cherokee leadership in the process. Under this false treaty’s authority, federal troops rounded up the Cherokee people and sent them west on what became known as the Trail of Tears.

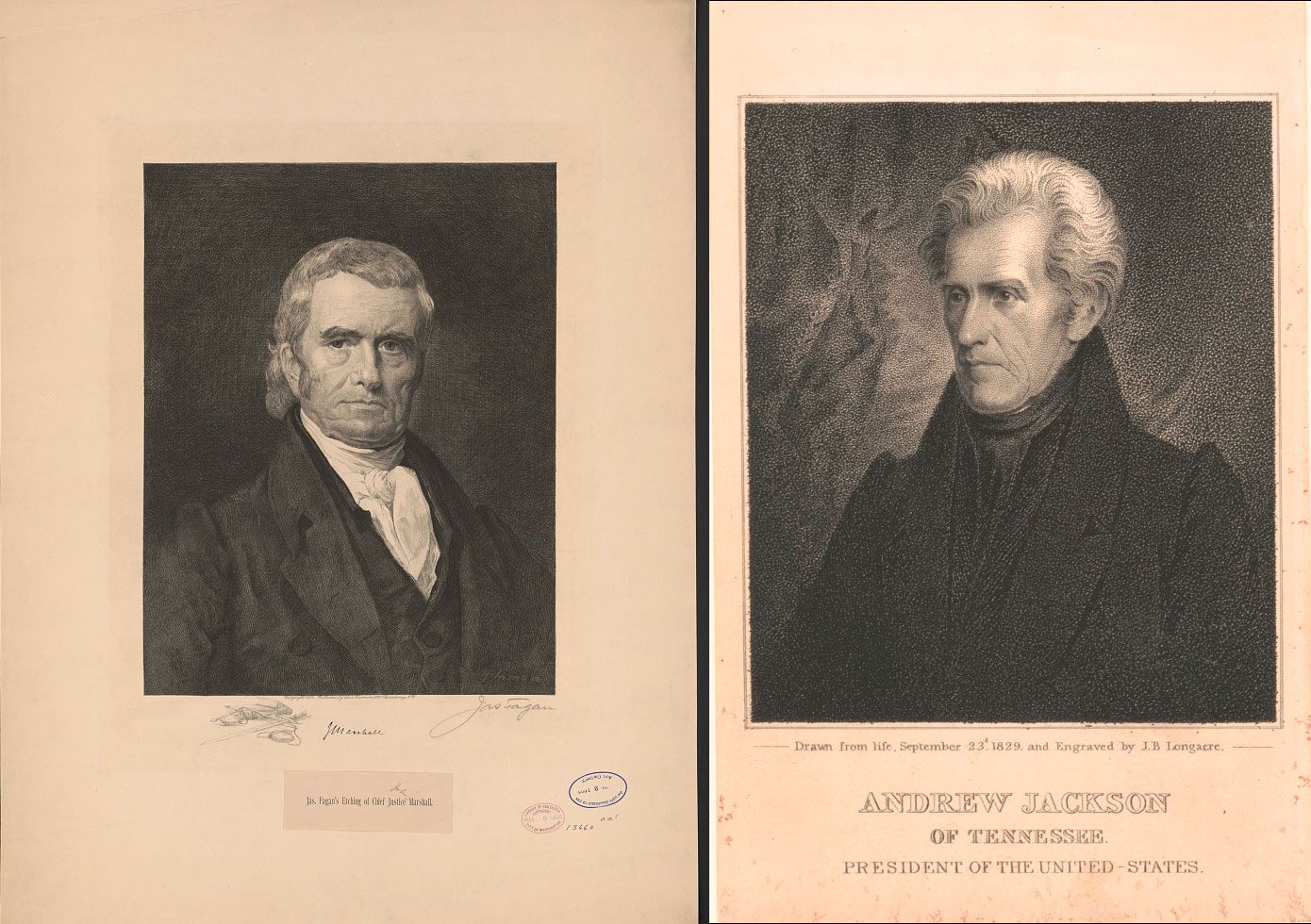

Feature image: Portraits of Chief Justice John Marshall and President Andrew Jackson (Source: Library of Congress)