“Language: A Key Mechanism of Control”

As head of GOPAC, Newt Gingrich encouraged GOP candidates to use combative language that drew a stark contrast between Republicans and Democrats as a means of attracting media attention. It was so effective that within 15 years, the red-blue divide had become the narrative framework for discussing American politics.

Gingrich’s rise to the GOPAC chairmanship and later, to Speaker of the House, was propelled by his recognition that media attention is equal to political power, and that political conflict and controversy is what the media thrived on. Through GOPAC, he made sure others in the party followed his lead.

He transformed GOPAC from its primarily fundraising role to a center for recruiting and training the next generation of Republican candidates. GOPAC mailed out cassette tapes and pamphlets for candidates to learn key Republican talking points. By one count, almost half of Republicans newly elected to the House of Representatives from 1990 to 1994 had received GOPAC training.

John Boehner, who was first elected to the House in 1990 and later served as Speaker for five years, told the Washington Post in 1994, “If it weren’t for the tapes, I probably wouldn’t have run for Congress.”

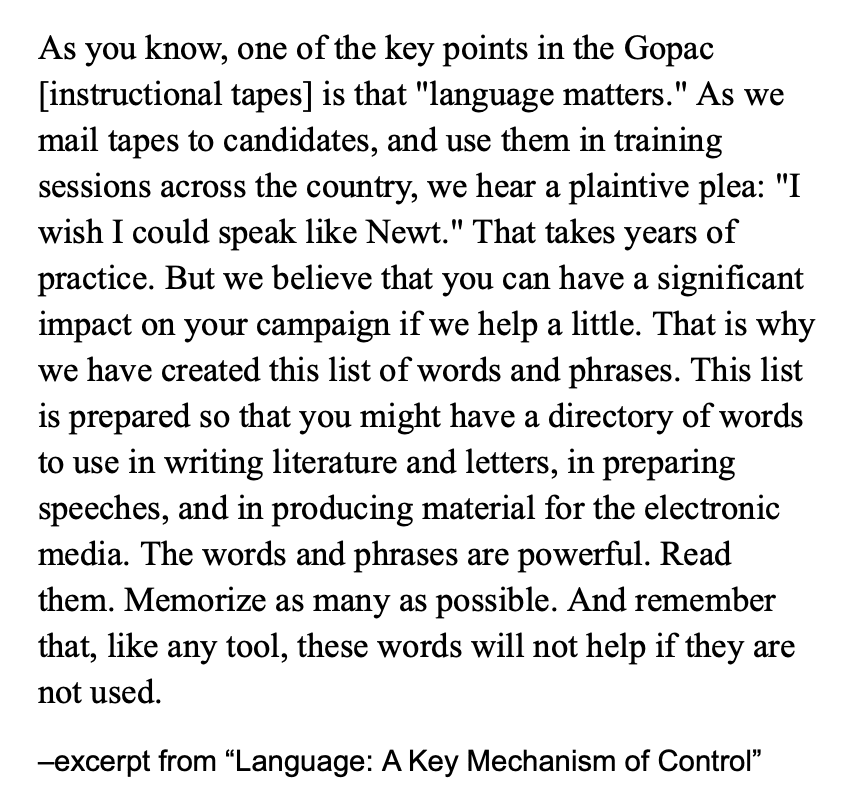

One particular pamphlet that received a lot of attention at the time was titled, “Language: A Key Mechanism of Control”. Market tested by Frank Luntz, it was designed to help candidates learn to “speak like Newt” – that is, to appeal to populist anger and frustration with those in government. The pamphlet identified lists of terms, culled from Luntz’ focus groups, that Republican candidates were encouraged to use to emphasize sharp distinctions between themselves and their Democratic opponents.

The training reflected a deep understanding of how the news media works: As Jon Allsop, an editor with the Columbia Journalism Review, wrote recently, “The political media does itself seek to define candidates – often out of what I see as a lazy impulse to boil complicated elections down to narratives of clear contrast.”

Gingrich’s material provided that clear contrast – a relatively simple message that branded Republicans as the pro-family, law and order, common sense party of patriots, and Democrats as corrupt traitors who were anti-flag and anti-child.

It didn’t matter whether there was any truth to the characterizations nor that Gingrich and his colleagues were now all too willing – and frequently so – to call into question the good intentions and the patriotism of their liberal colleagues. He had a most anti-democratic mindset – that politics is war, and only his side was good for the country. And as he rose through the Republican Party on his way to the speakership and more Republicans were elected, his colleagues – even the more constitutionally-minded among them – willingly adopted or only mildly objected to his methods.