The Election of 1800

An Electoral College tie in the race for president and the emergence of competing national political factions threatened to destabilize the country. In the end, the conflict surrounding this election’s outcome was resolved, sending a message to the country and to the world that the novel American experiment of republican government could endure.

Issue

In 1800, United States politics was dominated by two loosely-organized coalitions representing different visions for constitutional interpretation. In the presidential election that year, the Federalist faction was led by the incumbent President John Adams and his running mate Thomas Pinckney. The Democratic-Republican challengers were Thomas Jefferson and his vice-presidential candidate Aaron Burr.

At the time, the Electoral College did not distinguish between the presidential and vice-presidential ballots. The candidate with the most votes in this general ballot would be president and the second-most vice president, regardless of whether they were members of the same party or whether – or not – the leading vote-getter was his party’s designated presidential candidate.

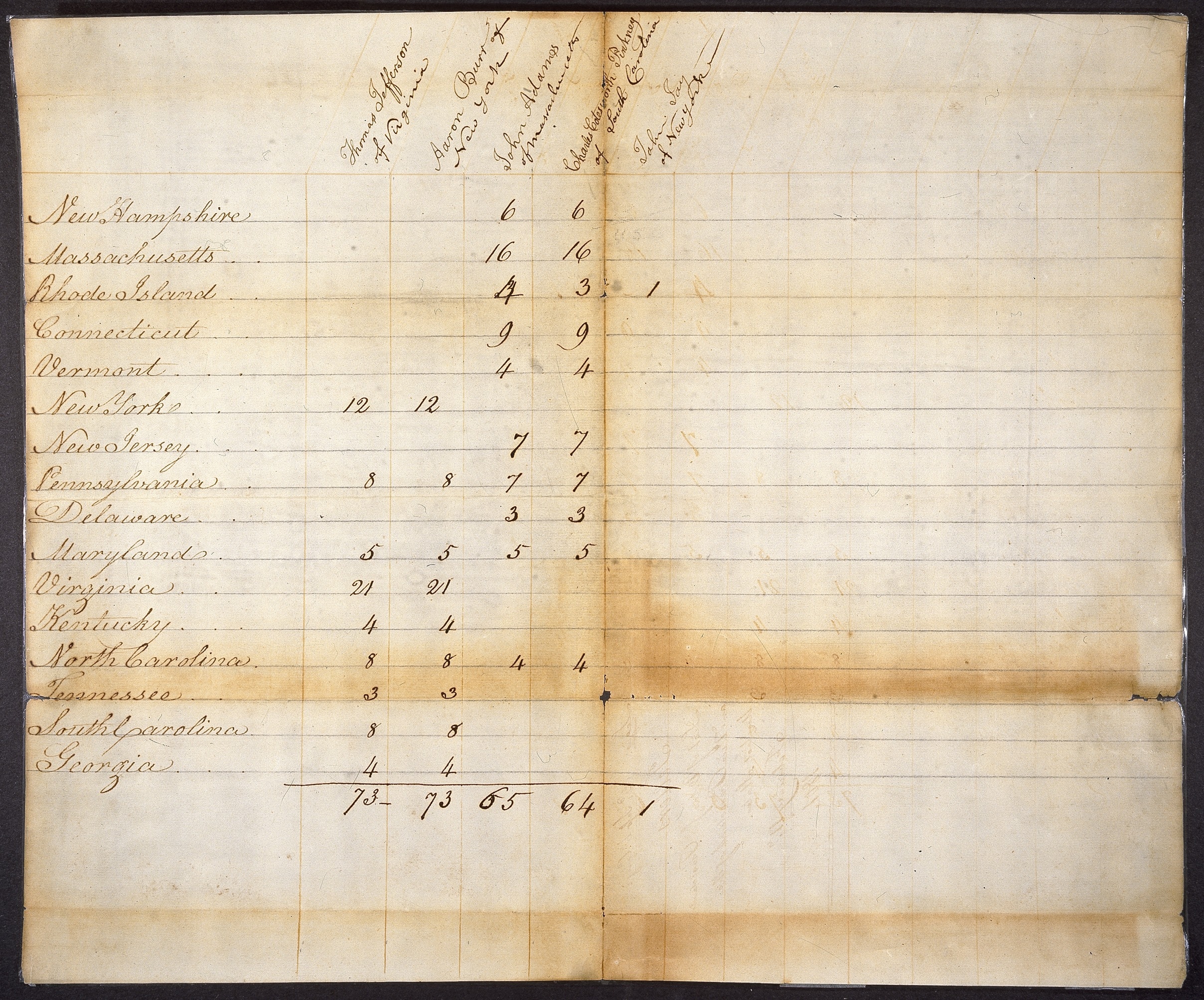

The poorly organized Democratic-Republican electors failed to arrange their votes effectively, and their two nominees tied for first place. Even though the Democratic-Republican nominees both beat the Federalist candidates, the tie meant that the new president was not conclusively elected. The Constitution states that an electoral tie throws the decision to the House of Representatives. There had previously been an informal recognition of the hierarchy of Jefferson over Burr, but in the eyes of the Constitution, both were equal contenders in the upcoming House contest.

While the House Democratic-Republicans were committed to supporting Jefferson, the Federalists saw an opportunity. Jefferson was a southerner and the leader of the opposition to Federalist ideology; Burr, on the other hand, was a New Yorker and an opportunist, not an ideologue. House Federalists began to rally behind Burr, believing that if they delivered him the presidency, he would be sympathetic to Federalist policy. Burr would not vocally accept Federalist endorsement, but also refused to defer to Jefferson. Despite objections from Federalist leaders such as Alexander Hamilton, John Marshall, and eventually President Adams himself, most House Federalists committed to supporting Burr, leading to a deadlock in the House election.

After thirty-five votes, neither candidate could secure a majority, and militias mobilized in the South and North, ready to defend their candidate’s claim.

Causes

The presidential election process outlined in the Constitution failed to accommodate the rise of national political parties, and how those factions would affect a tie in the Electoral College vote. These factions were rooted in the large cultural and economic differences between the industrial, trade-focused, and Federalist North and the agricultural, slave-dependent, and Democratic-Republican Southern states. Due to these divisions, many of the Founding Fathers openly questioned the long-term viability of the Union they had created. This group of doubters included Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, who were, at the same time, leading proponents of the Constitution. The Adams Administration inflamed these divisions through many policy decisions that were deeply unpopular with the Democratic-Republicans, most notably the Alien and Sedition Acts.

The media landscape in the first decades of the Republic was dominated by forthrightly partisan newspapers and pamphlets, sometimes directly sponsored by politicians themselves. In the year before the election, these papers elevated national tensions by viciously attacking opponents’ characters and peddling in conspiracy theories. They wrote about fake assassination attempts, about allegations that the other side wanted to burn the Constitution, that the Federalists would take Washington by force in the event of their defeat, and that Thomas Jefferson wanted to appoint himself King.

Outcome

Fearing disruption to what many saw as a fragile union, a group of House Federalists from Delaware indicated they would be willing to switch their votes if they received commitments from prominent Democratic-Republicans that the incoming administration would not dismantle key Federalist accomplishments like the maintenance of the public credit. After obtaining such assurances, the Delaware Federalists voted for Jefferson and secured his election.

Though violence almost erupted over the process, power peacefully transferred from one faction to another for the first time in American presidential politics. This election signaled to the world that America’s republican experiment could endure.

In 1803, the 12th Amendment was adopted, which created separate Electoral College ballots for the two offices so that each elector could separately and specifically vote for their party’s presidential and vice presidential candidates. This alleviated the need for the kind of elector coordination that led to the crisis in 1800. The 12th Amendment, however, did not alter the way in which an inconclusive or tied Electoral College vote would be resolved. Such elections would still be thrown to the House of Representatives, as it was in 1825.

The Federalists would never again hold federal executive office. In the intervening years, Jefferson’s administration and the subsequent Democratic-Republican administrations expanded voting rights for new White immigrants from Europe, which further secured their grip on power. At the same time, the Democratic-Republicans were the strongest proponents for the expansion of slavery and cotton production into the Mississippi territory as well as the removal of Native Americans from land that had long been their home.

Feature image: Vote tally in the election of 1800 shows a tie between Jefferson and Burr, with each candidate receiving 73 votes (Source: National Archives)