Threats to Election Security

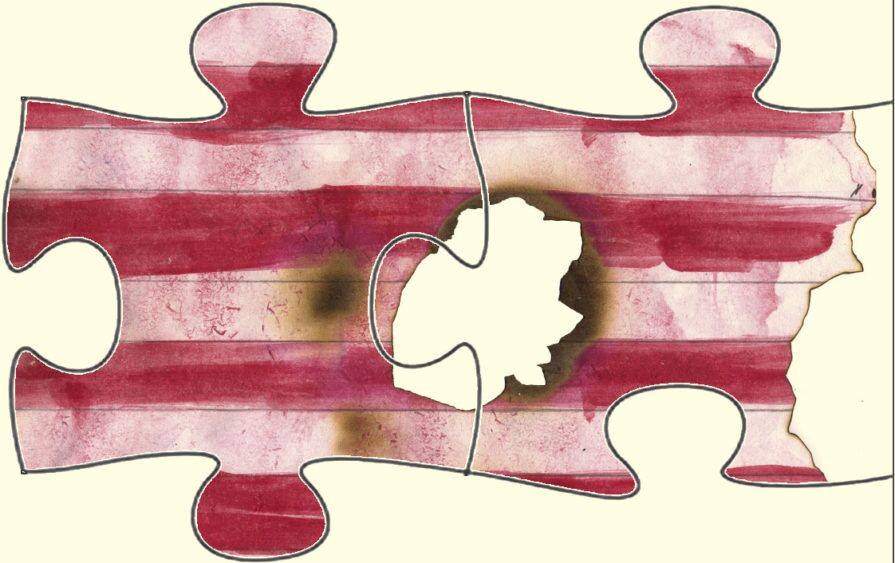

Elections in the United States are almost entirely safe and secure from tampering. The decentralized nature of our election system – states establish their own processes and protocols and generally distribute authority to the local level – make it extremely difficult for any coordinated attempt to undermine the results of statewide or federal elections by altering vote totals. Nonetheless, some vulnerabilities could be exploited if we are not vigilant, including a limited potential for election fraud, the somewhat greater threat of hacking electronic voting systems, and the more prevalent risks from domestic and foreign interference.

Domestic and Foreign Interference

Concern about foreign involvement in American elections dates back to the nation’s founding. The authors of the Constitution provided several safeguards against foreign interference, including prohibitions against a foreign-born, naturalized citizen becoming president and against any federal official receiving gifts from foreign governments.

Recent decades have shown how interference can take many other forms, and foreign governments will often leverage domestic organizations to achieve their goals. Before the 1984 election, for example, the Soviet Union, which had a long history of seeking to interfere in our elections, took covert actions in an effort to prevent the reelection of President Ronald Reagan, including trying to infiltrate both the Republican National Committee and Democratic National Committee.

The fall of the Soviet Union did not end the Kremlin’s efforts to interfere in our politics. In 2016, Russia made a two-pronged attack, hacking into the voting systems in all 50 states (although there is no evidence that they did anything once they had hacked in) and spreading disinformation across social media.

Also in 2016, candidate Donald Trump, at a July news conference, urged Russia to hack Hillary Clinton’s email. An indictment filed by Special Counsel Robert Mueller two years later claimed that the first attempts to hack into Clinton’s emails occurred on or around the same day that Trump issued his invitation. Sometimes, foreign interference may look a lot like domestic interference.

Whether this was coincidence or an indication of collaboration between Trump and Russia is among the many uncertainties that continues to fuel suspicion that Trump’s fealty to the Constitution, democratic norms and even federal law is readily swayed by the influence of foreign autocrats. And nowhere is this more apparent, and alarming, than his approach to Russia and Putin. We don’t have enough information to confirm that Trump collaborated with Russia but we do know that many of Trump’s actions as a candidate, as the president and since he left the White House, are consistent with Russian objectives, none more so than his claims of a stolen election.

Well before the 2020 election, election security experts had expressed concern about Russian efforts to undermine American democracy. As Ohio Secretary of State Frank LaRose (R) explained at a cybersecurity summit in 2019, “If we keep telling voters that elections are screwed up then they’re going to start believing us and stop voting. Having American citizens occupied with that narrative is what foreign autocracies want. They want Americans to lose faith that their vote counts.”

The claims repeated by Trump and other Republican leaders inspired the January 6 attack on the Capitol and encouraged the introduction of new mechanisms to limit the casting and counting of ballots. Considered together, those actions, including tampering with mail delivery, falsifying states’ slates of electors, and limiting the independence of election oversight, all constitute an attack on American democracy and reveal vulnerabilities in the electoral system that previously had not warranted much, if any, concern.

Mail slowdown

The coronavirus pandemic began during the 2020 primary season and prompted nationwide anxiety about the health risks of voting in person. Under pressure from Democrats and voting rights groups, 34 states made it easier to vote in the general election. Most of the changes promoted voting by mail and eased the rules governing the completion and tabulation of absentee ballots in order to reduce the number of people coming to the polls and putting themselves and election workers at risk of infection.

This shift away from in-person voting prompted President Trump to assert that increased mail-in voting would prevent Republicans from ever getting “elected in this country again.”

When Trump’s appointee as Postmaster General, Louis DeJoy, took office in June 2020, critics feared that the changes he proposed and implemented would slow the delivery of an unprecedented volume of mailed ballots. Those changes included removing mailboxes, canceling delivery runs, and closing down sorting centers. Trump opposed providing additional funds to the Postal Service because, he said, if the Democrats “don’t get the money, that means they can’t have universal mail-in voting.”

Amid substantial backlash, including several lawsuits and a congressional inquiry, both Trump and DeJoy reversed course in August. In September, two months before the election, a federal court ordered USPS to implement several actions, including prioritizing delivery of election mail and pre-approving overtime for postal workers in the week before the election. And in October, the USPS inspector general conducted unannounced visits to more than 1800 sites in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. In the week before the November 3 election, inspectors conducted another 83 announced site visits.

In March 2021, the inspector general issued a mostly favorable report based on its findings, noting in particular that the Postal Service had effectively “prioritized processing of Election Mail during the 2020 general election, significantly improving timeliness over the 2018 mid-term election even with significantly increased volumes of Election Mail in the mailstream.

Falsifying electoral votes

President Trump and his supporters took two significant actions related to electoral votes in hopes of reversing his defeat. The first was what now appears to be a coordinated effort by high-ranking Trump campaign officials to encourage falsification of documents in order to create alternate slates of electors supportive of Trump. The effort targeted seven states, including four of the swing states essential to Joe Biden’s victory: Arizona, Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Dismissed at the time by most observers as wishful thinking, attorneys general in Michigan and New Mexico have requested that federal prosecutors investigate this action.

The second action focused on the role of the vice president in the process of certifying the electoral votes. Trump and his team argued that Vice President Mike Pence, who under the Constitution presides at the joint session of Congress where Electoral College results are tallied and affirmed, could reject votes for Biden in favor of the alternate slates of electors in the seven states. Pence announced that he did not believe he had such authority on January 6, 2021, just before the joint session was to begin and while a crowd of Trump supporters marched toward the Capitol. Several hundred forcibly entered the building, some chanting “Hang Mike Pence”. Once the Capitol was breached, the proceedings were suspended, the House and Senate chambers were evacuated and members were rushed underground to secure locations.

As with the investigation around the creation of alternate slates of electors, details emerging from the House investigation into the January 6 insurrection suggests that the attack on the Capitol may also have been coordinated by members of Trump’s inner circle.

Reducing the independence of election overseers

In what would make it easier for an eventual power grab, Republicans in control of several state governments are pushing for state election law changes that would diminish independent oversight in favor of more partisan control of elections. They have succeeded in doing so in at least eight states, according to an analysis by ABC News. Coupled with public calls in several of those states to decertify the 2020 presidential election results, these efforts, even when unsuccessful, further contribute to the erosion of trust in American democracy.

Who Votes May Matter Less Than Who Counts the Votes

While much attention has been given to the dozens of proposed and passed laws aimed at suppressing turnout in elections, the Brennan Center for Justice issued a report late in 2021 that focused on new laws that target who gets to count the vote.

Following a legislative season that saw many states increase barriers to voting, these laws and proposals, often added quietly and late in the legislative process, would change who runs elections, who counts the votes, and how. They go beyond vote suppression to enable direct election subversion. And they have a distinctly authoritarian flavor. Joseph Stalin put it pungently: “I consider it completely unimportant who in the party will vote, or how; but what is extraordinarily important is this — who will count the votes, and how.”

—Will Wilder, Derek Tisler, and Wendy Weiser, from The Election Sabotage Scheme and How Congress Can Stop It

Despite the report’s intent, stated plainly in its title, to encourage Congress to pass legislation that could prevent states from overturning legitimate elections, Congress has as of this writing failed to act.

Election security expert David Becker, who had sounded confident in 2020 that the system of election administration would be free of corruption, told CNN in 2022 that he has changed his mind: “Every day that goes by, I am more and more concerned about the direction and resilience of American democracy. I’m worried that we are heading down a path where there are those who cannot accept that … their candidate could lose.”

In 2020, Becker had placed his faith in the people who oversee the voting at the state and local levels. But in Georgia, where Secretary of State Brad Raffensberger (R) famously refused Trump’s request “to find 11,780 votes, which is one more than we have,” the legislature has since passed a law that removes the secretary of state from his oversight role as chair of the state election board. Now, the heavily Republican legislature is able to appoint someone it views as more reliably partisan to the position.

The Arizona legislature, also with a Republican majority, took a similar step to weaken the oversight authority of the secretary of state, who is currently a Democrat. A law passed in June 2021 establishes the attorney general, who is currently a Republican, as the “sole authority” to defend state election laws. Both positions will soon be held by newcomers because the incumbents are not seeking re-election in 2022. The law expires in January 2023 in what seems to be an overt attempt to defuse its effect should a Democrat be elected attorney general.

And in Texas, a law enacted in 2021 gives poll watchers freedom of movement inside polling places and limits the ability of election officials to remove poll watchers whose actions and presence are seen as intimidating to voters. Election officials are now subject to up to six months in jail and a $2,000 fine for improperly interfering with a poll watcher. The law also restricts what assistance can be provided to voters.

In all these cases, the new statutes were justified as a way to combat voter fraud and election rigging, although such claims have all proved false or wildly exaggerated.

The widely accepted interpretation of Article 1, Section 4 of the Constitution is that states are empowered to make the rules that govern their congressional elections, although those rules can be superceded by Congress. But in Congress, the GOP has been unified in opposition to voting rights legislation that could restore some confidence that elections in the states in question will be overseen by people committed to preserving the right to vote, and not by political partisans.

Hacking

The decentralization of the American election system is both a curse — it leaves more doors for hackers to penetrate — and a blessing, as any potential vulnerabilities tend to be localized. But in 2016 Russian hackers nonetheless targeted election systems in all 50 states and gained access to a “small number” of networks, the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence concluded in 2019, although it found no evidence that any votes or voter data was changed.

The Department of Homeland Security told the committee it was unclear why the Russians didn’t go further but suspected that altering data was not the Kremlin’s goal, suggesting instead that “it fits under the larger umbrella of undermining confidence in the election by tipping their hand that they had this level of access or showing that they were capable of getting it.”

US cybersecurity experts were caught off guard by the extent of the attacks in 2016. Over the next four years, they scrambled to be better prepared for 2020. In those years, our cyber defense system heightened vigilance for cyber threats and improved communication channels between federal, state, and local election officials. Many states also updated or replaced old and potentially vulnerable voting systems. Still, several areas of concern have gone largely unaddressed, including independent vulnerability testing of electronic voting systems, or have proven more challenging, such as controlling the spread of disinformation on social media. And Congress was slow to provide sufficient funding to the states for some of the upgrades needed.

Despite the system’s remaining vulnerabilities, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, an arm of the Department of Homeland Security that monitors threats to elections, released a statement soon after the 2020 election calling it the “most secure in American history.” The statement also noted that “all states with close results” have paper records of every vote, and stressed that “there is no evidence that any voting system deleted or lost votes, changed votes, or was in any way compromised.”

Nevertheless, the Trump team launched an aggressive campaign to convince the nation the election had been rigged against him.

But even so-called audits by Trump partisans concluded that he did not win in either Arizona or Pennsylvania, two of the states where he most vociferously contested Biden’s win. (In the process of conducting the audits, the investigators compromised the integrity of the voting systems, which required that the states replace them for the next election. )

In addition, senior members of Trump’s legal team accused two leading vendors of electronic voting systems, Dominion Voting Systems and Smartmatic, of contributing to the fraud – allegations which resulted in defamation lawsuits from both of them.

False Accusations and the Damage Done: A View from the Right

Ten days after the election, Julian Sanchez, a senior fellow at the libertarian Cato Institute, wrote:

“Donald Trump’s crusade to manufacture doubts about the outcome of the presidential election reached a new low on Thursday, when the president shifted from making vague, evidence‐

This is embarrassing nonsense of the sort one expects to see on fringe message boards, not emanating from the White House.”

Then, in The Atlantic a month later, he wrote:

“After losing to Joe Biden in November, President Donald Trump has been amplifying conspiracy theories about electronic voting without knowing or caring just how much this year’s swing states have done to protect the integrity of their elections. False claims that voting machines were “rigged” to change or delete votes—accepted by a disturbingly large percentage of Trump supporters—are harmful for obvious reasons: They wrongly undermine confidence in the democratic process, and have spurred harassment and threats aimed at election officials and poll workers. But they also give the public a wildly distorted picture of election cybersecurity, ignoring states with real security problems to address while perversely sowing doubts about states that have followed all the best expert advice.”

Voter and Election Fraud

Despite intensifying Republican allegations of voter and election fraud over several decades, very little cheating actually occurs. The Brennan Center’s 2007 report, The Truth About Voter Fraud, estimated fraud incident rates were less than one-one-hundredth of 1%. More than two dozen studies, court opinions, and government investigations have concluded that voter fraud is virtually non-existent and has no impact on election results.

In a more recent report from December 2021, the Associated Press reported that it had found no more than 475 cases of potentially fraudulent votes in the six battleground states that Trump lost and then disputed the results. That statistically insignificant number of ballots would have made no difference in the 2020 outcome – even if all the questionable ballots were for Biden, which they were not, and even if those ballots were counted, which in most cases they were not. Biden won Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin and their 79 Electoral College votes by a combined 311,257 votes out of 25.5 million ballots cast for president. The disputed ballots represent less than 1% of his victory margin in those states.

Efforts to stop fraud, however, can alter election outcomes. Voter purges, as we’ve seen, can exclude thousands of eligible voters. A 2019 study estimated that one mechanism for thwarting people who try to vote more than once would prevent 300 legitimate voters from casting a ballot for every potential double-voter purged. And two venerable jurists – Justice John Paul Stevens and federal appeals court Judge Richard Posner – who both had voted to uphold a strict voter ID law in Indiana, later expressed regret over doing so. Posner acknowledged that Indiana’s type of ID law has since become recognized as a greater means of voter suppression than a means of preventing fraud, suggesting that the law was excessive in view of what he now understood was a limited threat from voter fraud.

And while Republican allegations come with the presumption that cheating is dominated by Democrats, a scan of the Heritage Foundation’s election fraud database suggests instead that it is very much bipartisan.